경북과 강원지역 농업생태계에서 여름철 화분매개네트워크 다양성과 상호작용

Abstract

Pollination is an important ecosystem service involved in plant breeding and reproduction. This study analyzed the pollination network, which is the interaction between flowering plants and flower-visiting insects in the agricultural landscape. Flower-visiting insects from blossoms of flowering crops and surrounding plants were quantitatively surveyed during summer time. The pollinator species and abundance on each flowering plant were analyzed. A total of 2,381 interactions were indentified with 154 pollinators on 30 species of plants. Species richness of the pollinators was highest in Coleoptera (34%) followed by Hymenoptera (28%), Diptera (28%) and Lepidoptera (10%). Apis mellifera dominated (50%) followed by Calliphora vomitoria (5.3%) and Xylocopa appendiculata among pollinators, and remaining wild pollinators provided complex interaction. Among plants, Platycodon grandiflorum, Perilla frutescen and Fagopyrum esculentum harbored most pollinators and showed highest interaction frequencies. In the modular analysis, Apis mellifera was located as a hub-species which connect the interaction of others, implying most important role in the network. This results provide the basic information on the pollinator species associated with each crop and pollinator habitat in which plant provide the nectar, pollen and habitat resources for wild pollinators.

Keywords:

Platycodon grandiflorum, Perilla frutescent, Fagopyrum esculentum, Modularity, hub-species, Calliphora vomitoria서 론

전 세계에서 중요시되는 주요 작물들 대부분은 수분을 위해서 화분매개자를 필요로 한다(Klein et al., 2007; Garibaldi et al., 2013; Choi and Jung, 2015; Ghosh and Jung, 2018). 또한, 벌 등 다른 여러 화분매개자들은 수확의 양과 질에 큰 영향을 줄 수 있는 요인이며, 작물 생산에 귀중한 자원으로 이야기할 수 있다(Ricketts et al., 2008; Cussans et al., 2010). 그런데 오늘날 농업생태계는 인간이 원하는 작물의 높은 생산성을 위하여 식물의 종류는 대체적으로 제한되어 있다(Ricketts et al., 2008; Hagen and Kraemer, 2010; Gilpin et al., 2019). 게다가 농업을 위한 토지이용 강화로 화분매개자들의 서식지가 줄어들고 있다(Giulio et al., 2001; Grab et al., 2017; Santamaria et al., 2018). 작물의 단일화는 화분매개자의 다양성에 영향을 줄 수 있다(Naggar et al., 2018; Topp and Loos, 2019). 또한, 꽃의 양이 많은 곳에서는 주변 화분매개자들을 끌어들이는 효과가 있는데(Gilpin et al., 2019), 서식지의 파괴는 이러한 화분매개자들의 다양성이나 개체 수를 감소시키고, 결국에는 작물의 질과 생산량에도 영향을 줄 수 있는 것으로 나타나고 있다(Bierzychudek, 1981; Ebeling et al., 2008; Diekotter et al., 2010; Holzchuh et al., 2011). 더 나아가, 광범위한 토지에서의 편리한 관리를 위하여 농경지와 삼림이 대부분 조각화(Fragmented)되어 있는 것을 볼 수 있으며(Jennersten, 1988; Jauker et al., 2019), 이는 곧 생물 종 다양성 감소 및 개체들의 고립을 야기할 수 있다고 한다(Topp and Loos, 2019).

생태계에서 생물종들은 다양한 상호작용을 하며 공생관계를 유지하고 있다(Proulx et al., 2005). 포식, 기생, 화분매개 등 복잡한 생물 상호작용 네트워크는 생물 다양성을 유지하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다(Altieri, 1999; Bascompte and Jordano, 2007). 이러한 상호작용 네트워크는 생물 다양성 연구를 하는 데 있어서 매우 중요한 부분을 차지하고 있다(Basilio et al., 2006). 상호작용 네트워크의 구조와 기능에 대한 우리의 이해는 여러 가지 관련 이론들을 통하여 가속화되고 있는 상황이다(Bascompte, 2007; Olesen et al., 2008). 네트워크이론 중 화분네트워크(Pollination Network)는 현화식물 - 화분매개자 간의 상호작용 네트워크로서 생태계의 구조와 기능 연구에 유용하다(Olesen and warncke, 1989; Memmott, 1999; Olesen et al., 2002). 화분매개네트워크 분석은 식물과 방화곤충과의 관계를 설명해 줄 뿐 아니라 생태계의 복잡 다양한 생물상의 구조를 이해하는 데 도움이 된다. 더 나아가, 화분매개네트워크분석은 모듈화나 절멸에 대한 시뮬레이션 등 생태계 내 패턴을 확인하거나 예측하는 데 큰 도움이 될 수 있다(Danieli-Silva et al., 2012). 화분매개네트워크 분석은 생물 간의 연결도(Connectance), 종간중첩성(Nestedness), 분포도(Degree distribution), 상호작용 다양성(Interaction diversity), 상호작용 강도나 균등도(Interactnion strength, evenness) 등의 정보 또한 제공한다. 네트워크 분석은 식물 - 화분매개자 관계를 요약하며, 생태환경 요인의 구배에 따른 생태계의 일반적 또는 전문화된 상호 관계를 도식화하고 동시에 기능적 구획을 식별할 수 있게 한다(Basilio et al., 2006). 특히 특정 지역의 환경 요인이나 경관 요소는 화분매개자 군집의 구조와 다양성 그리고 기능적 관계에 영향을 미치는데, 그 방식과 크기는 요인의 종류, 지역, 시기 등에 따라 다르게 나타난다(Ricketts et al., 2008; Dupont et al., 2014; Bennett and Lovell, 2019). 특히 농업생태계에서는 화분매개의 양과 품질은 농업 생산성과 지역 농가의 수익 창출에 직접적 영향을 미치기 때문에, 화분매개네트워크 보호 및 복원은 더욱 중요해진다(Potts et al., 2010; Wratten et al., 2012; Frank et al., 2019). 그럼에도 불구하고, 국내 화분매개시스템에 대한 연구는 화분매개의 가치(Jung, 2008; Ghosh and Jung, 2016), 화분매개자의 종 구성과 방화활동(Kim et al., 2009; Choi and Jung, 2015), 화분매개자의 독성(Kim et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2016) 그리고 화분매개서식처의 기능(Lee and Jung, 2019) 등이 이루어지고 있으나, 농업생태계 화분매개네트워크에 대한 연구는 매우 제한적이다.

본 연구는 경북 주요 지역과 강원, 평창에서 여름철 개화작물과 주변 개화식물에서 화분매개자를 조사하고 식물 - 화분매개자 관계를 다음의 목적을 가지고 분석하였다. 첫째, 여름철 농경지에서의 식물 - 곤충 화분네트워크의 구조를 분석한다. 둘째, 분류군별 주요 화분매개자와 식물 간의 상호작용 관계를 확인한다. 셋째, 네트워크 내에서 모듈화를 진행하고 각 모듈에 대한 분석을 확인하여 네트워크 속 중요종을 확인한다. 본 연구의 결과로는 국내 농업생태계 내 화분매개네트워크의 구조를 확인하고, 화분매개자의 서식처 증대 및 보존을 위한 기초 자료를 제공할 것이다.

재료 및 방법

1. 화분매개자 조사 지역과 방법

본 조사는 2016년 7월과 8월에 경상북도 8개 지역(문경, 봉화, 상주, 안동, 영주, 예천, 의성, 청송)과, 강원도 평창군에서 이루어졌다(Table 1). 농업생태계 화분매개자 조사의 범위는 개화 중인 재배 작물을 중심으로 주변에 분포하는 주요 개화식물 중 지표 면적이 10 m2 이상 군락이 형성되거나 연결된 식물을 대상으로 하였다. 꽃을 방문하는 곤충 중 식물의 꽃잎이나 꽃 중앙에 앉는 화분매개자들을 대상으로 하였으며, 화분매개자에 주로 포함되는 4가지 목(딱정벌레목, 파리목, 나비목, 벌목)을 대상으로 하였다. 그 외에 잎이나 줄기에 앉는 경우는 분석에서 제외하였다. 각 지역에서 개화 작물이나 주변 식물별로 평균 5분 정도 가로지르며 한번만 조사하였으며, 꽃에 앉아있는 화분매개자들을 기록하였고, 분류동정이 필요한 종의 경우 포충망을 이용하여 포획한 뒤 실험실로 가져와 전문가의 도움을 받아 식별하였다.

2. 식물 - 화분매개자 화분매개네트워크 분석

식물 -화분매개자 양자 간 네트워크 분석은 R 통계프로그램의 Bipartite package (R core team, 2008)를 이용하였다.주요 화분매개자 집단을 4가지 목(Order)으로 구분하고 상호작용 빈도수와 종수로 구분하여 각 분류군의 비율을 계산하였다. 각 식물 종을 방문하는 주요 화분매개자들을 식별한 뒤 전체 네트워크 속에 존재하는 작은 커뮤니티 집합들의 존재를 분석하였고, 집합 간 연결을 담당하는 핵심 종이 무엇인지 확인하기 위하여 모듈화를 진행하였다(Olesen et al., 2007). 모듈화에 대한 알고리즘은 Beckett(R core team, 2008)의 것으로 계산하였다.

결과 및 고찰

1. 농업생태계 화분매개네트워크

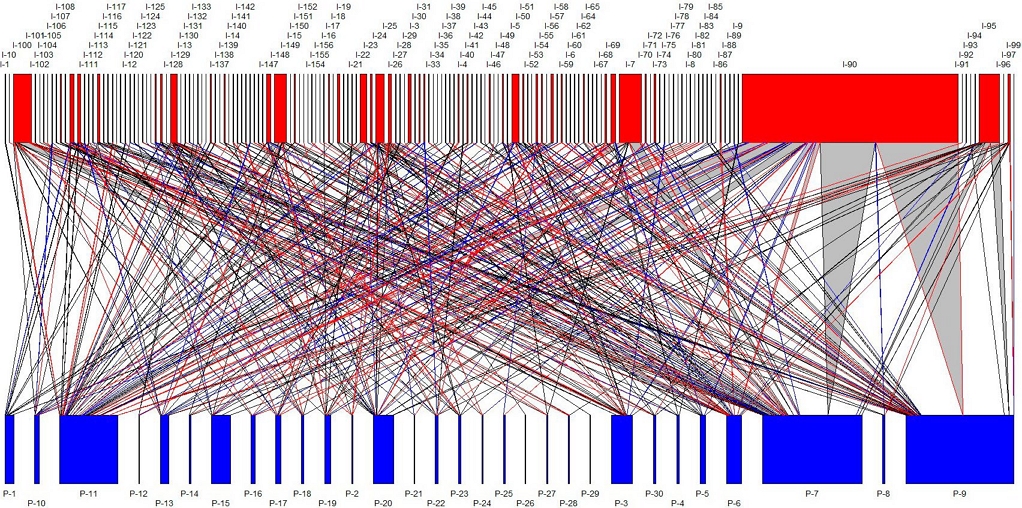

전체 농업생태계의 식물 - 화분매개자 화분네트워크에서 총 2,381개의 상호작용이 관찰되었으며, 식물은 14목 17과 28속 30종, 화분매개자는 4목 52과 129속 154종이 나타났다(Fig. 1; Table 2). 식물 종에서는 들깨(P-9; Perilla frutescens var. japonica)가 26.2%로 가장 많은 상호작용 참여도를 보였으며 도라지(P-7; Platycodon grandiflorum)가 24.4%로 두 번째로 많은 상호작용 참여도를 나타냈고, 메밀(P-11; Fagopyrum esculentum)이 14.2%로 그 다음으로 많았다. 들깨는 꽃당 화밀 생산이 많을 뿐 아니라, 화밀 내 당 구성이 높고 화분도 화분매개자들이 원하는 만큼 먹이자원을 충분히 가지고 있어(Consonni et al., 2013), 다양한 화분매개 곤충을 유인하는 것으로 보인다. 도라지는 보라색이고 꽃의 크기가 클 뿐 아니라 화밀량과 꽃가루가 많고, 항산화 활성이 높은 식물로서 호박벌 등 뒤영벌류에 대한 유인력이 높을 뿐 아니라 다양한 화분매개자를 지원한다(Jin and Jinzheng, 2001).

Pollination Network Structure in Agricultural ecosystems in Gyeongbuk and Kangwon provience. Top bars (red) represent the pollinator species and bottom bars (blue) the plant species surveyed. The lines between the bars indicate interactions among plants and pollinators. Each color of the lines representing the interaction distinguishes the strength of the interaction (black: strong, red: middle, blue: weakness). The thickness of the lines represents the frequency of interaction. The thickness of the bar indicates the frequency of interaction participation. I-90: Apis mellifera; I-7: Calliphora vomitoria; I-95: Xylocopa appendiculata circumvolans; I-100: Lucilia illustris; P-9: Perilla frutescens var. japonica; P-7: Platycodon grandiflorum; P-11: Fagopyrum esculentum.

Relative proportion of sample size of each plant surveyed (S, %), total pollinator frequencies(fp), and abundance of 4 major pollinator orders(Col; Coleoptera, Dip; Diptera, Hym; Hymenoptera, Lep; Lepidoptera)

화분매개자들 중 양봉꿀벌 (I-90; Apis mellifera)이 52.3%로 절반 이상을 차지하면서 화분매개자 우점종으로 나타났고, 검정파리(I-7; Calliphora vomitoria) 5.3%, 어리호박벌(I-95; Xylocopa appendiculata circumvolans) 4.9%, 연두금파리(I-100; Lucilia illustris) 4.4%로 나타났다. 벌류 중에서도 양봉꿀벌의 밀도가 압도적으로 높은 것을 확인할 수 있었고, 이는 과수나 다른 농작물에서도 꿀벌의 우점도가 70%를 상회한다는 보고와 비슷한 경향이다(Jung, 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Jung, 2014; Choi and Jung, 2015). 또한, 전체 화분매개자 중 양봉꿀벌을 제외한 나머지 46%에 해당하는 화분매개자들 역시 농업생태계 내 중요한 생태계 서비스 역할을 하는 것임을 확인하였다(Garibaldi et al., 2013).

식물별 주요 화분매개자의 비율은 다음과 같이 나타났다(Table 2). 전체 화분매개자 중 가장 많은 화분매개네트워크 참여빈도수를 나타낸 양봉꿀벌부터 검정파리, 어리호박벌, 연두금파리, 호박벌(I-148; Bombus ignitus) 순으로 표시하였다. 양봉꿀벌은 배롱나무에서 85.6%로 가장 큰 비율을 나타냈으며, 옥수수(67.5%), 도라지(55.2%) 순으로 나타났다. 검정파리는 풀협죽도 (16.7%), 메밀(12.5%)로 나타났다. 어리호박벌은 회화나무(31.3%), 백일홍(22.2%), 달맞이꽃(13.5%)으로 나타났다. 연두금파리는 두릅나무(57.1%), 금계국(52.0%), 풀협죽도(16.7%)로 나타났다. 마지막으로 호박벌은 무궁화 (30.6%), 접시꽃 (28.6%), 백일홍 (22.2%)으로 나타났다. 금잔화(Calendula officinalis), 코스모스(Cosmos bipinnatus), 개망초(Erigeron annuus), 호박(Cucurbita moschata), 원추리(Hemerocallis fulva), 모감주나무(Koelreuteria paniculata) 등 6종은 5종의 화분매개자들이 나타나지 않았다.

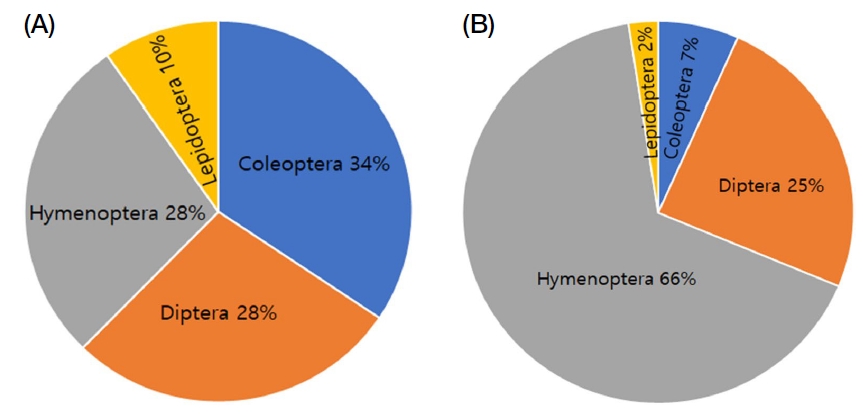

2. 화분매개자 분류군별 화분매개네트워크

상호작용이 가장 많았던 화분매개자 분류군(Fig. 2)은 벌목으로 66%였으며, 파리목 25%, 딱정벌레목 7%, 나비목 2% 순이었다. 양봉꿀벌에 포함된 벌목이 화분매개자 분류군 중 비율이 높았던 것을 알 수 있었다. 종의 수가 가장 많았던 분류군은 딱정벌레목(34%)이며, 벌목 28%, 파리목 28%, 나비목 10%로 나타났다. 상호작용 참여빈도수로는 딱정벌레목이 벌목보다는 낮았으나 종 다양성으로는 딱정벌레목이 더 많았다. 딱정벌레목은 다른 분류군들 보다 상대적으로 상호작용이 고르게 나타났는데, 꼬마남생이무당벌레(Propylea japonica)가 가장 많이 나타났으며, 두 번째로는 중국청남색잎벌레(Chrysochus chinensis)가 나타났다. 이 두 종의 화분매개역할은 잘 알려져 있지 않고, 초식을 하기 위해 꽃을 방문했을 가능성도 높다. 추후 화분매개네트워크 분석은 좀 더 화분매개 기능을 가진 곤충 군집으로 세분화할 필요가 있다. 식물 종은 도라지가 가장 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보이며, 메밀, 기생초(Coreopsis tinctoria)와 루드베키아(Rudbeckia hirta) 순으로 나타났다.

Relative proportion (%) of the species richness(A), and the number of interaction participated in the plant-pollinator interaction (B) per each order of insects.

파리목에서는 검정파리가 가장 빈번하게 나타났으며, 연두금파리와 꼬마꽃등에(Sphaerophoria menthastri) 순으로 나타났다. 식물 종은 루드베키아가 가장 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보였으며, 도라지, 들깨 순으로 나타났다.

벌목에서는 양봉꿀벌이 가장 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 나타냈고, 어리호박벌, 호박벌(Bombus ignitus) 순으로 나타났다. 식물 종은 들깨가 가장 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보였으며, 도라지, 메밀 순으로 나타났다.

나비목에서는 배추흰나비(Pieris rapae)가 가장 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보였으며, 꼬리명주나비(Sericinus montela), 애기나방(Amata fortunei), 줄점팔랑나비(Parnara guttatus) 등이 많이 나타났다. 화분매개자들이 가장 많이 찾은 식물 종은 도라지가 가장 많았으며, 들깨, 달맞이꽃 순으로 확인되었다. 결과적으로 루드베키아에서 딱정벌레목과 파리목이 공통적으로 많이 나타난 것을 확인할 수 있었으며, 도라지와 들깨에서는 벌목과 나비목이 공통적인 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보여 각 분류군별 선호도가 높은 식물이 다름을 확인하였다. 그리고 벌목, 파리목, 나비목에서는 공통적으로 도라지가 많은 상호작용 참여빈도수를 보여, 주요 선호종으로서 확인하였다.

다음은 식물별 주요 화분매개자들의 비율을 표(Table 3)로 나타냈다. 화분매개자 중에서 양봉꿀벌이 대부분의 식물들에서 높은 비율을 보이고 있었다. 하지만 금잔화, 코스모스, 개망초, 호박, 벳지, 원추리, 풀협죽도, 모감주나무, 고추에서는 나타나지 않는데, 해당 식물들에게 화분매개자로서 양봉꿀벌이 방화를 하지 않는 것은 아니지만 식물자원(Table 1)의 양이 상대적으로 다른 식물들보다 적어 상호작용 빈도수가 나타나지 않은 것으로 보인다.

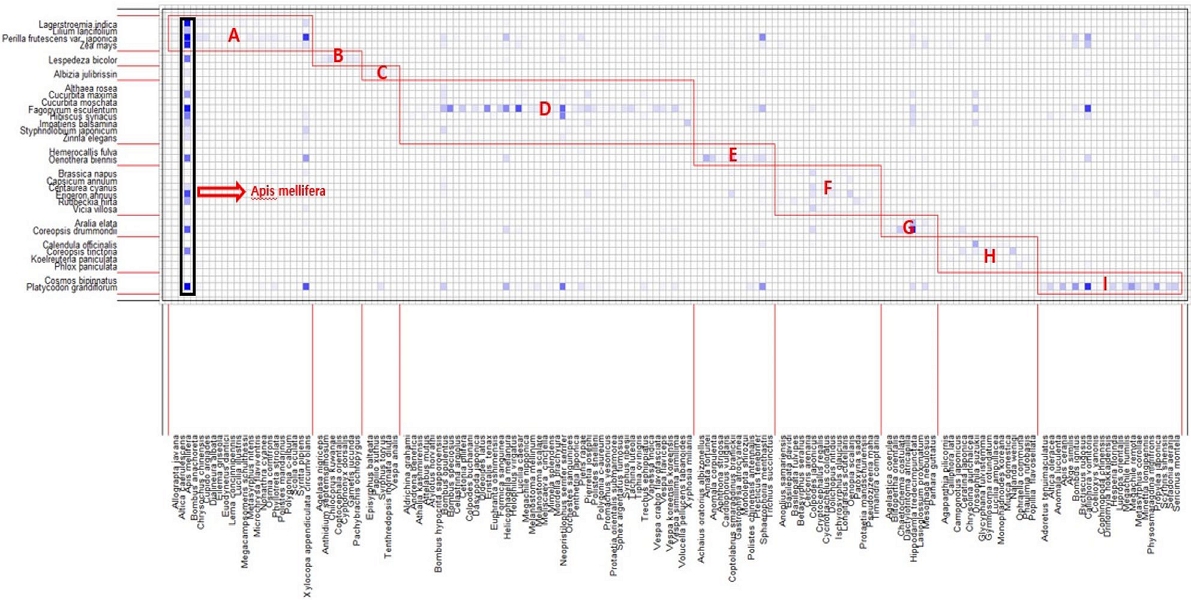

3. 화분매개네트워크 모듈화

경북과 강원지역 여름철 화분매개네트워크 속 소규모 집단의 구성을 확인하고 집단끼리의 관계를 이어주는 허브(Hub) 종을 알아보기 위하여, 모듈화를 실행한 결과가 다음과 같이 나타났다(Fig. 3). 그 결과 총 9개(Fig. 3 A~I)의 모듈이 생성되었다. 가장 큰 모듈화를 나타낸 집단은 D집단이며, 메밀, 무궁화(Hibiscus syriacus), 백일홍(Zinnia elegans), 접시꽃(Althaea rosea), 호박, 회화나무(Styphnolobium japonicum) 등이 포함되어 있다. 이 중 메밀과 무궁화는 호박벌과 가장 긴밀한 상호작용을 이루고 있어 주요 화분매개자로 자리잡고 있다. 양봉꿀벌이 포함되어 있는 집단은 A집단이며, 양봉꿀벌은 다른 대부분의 모듈 집단들을 이어주는 허브종으로서 나타나고 있다. 허브종은 그 종이 속한 모듈집단을 제외하고 다른 집단에 속한 종과 빈도수가 많았을 때 두 모듈을 이어주는 허브종이라고 이야기할 수 있다(Olesen et al., 2007). 허브종은 다른 모듈 집단에 영향을 줄 수 있는 종이며, 허브종 절멸 시 집단 간의 상호작용 역시 영향을 받을 수 있다. 여기 모듈 집단에는 배롱나무(Lagerstroemia indica), 옥수수(Zea mays), 참나리(Lilium lancifolium), 들깨 등의 식물 종들이 형성되어 있으며, 양봉꿀벌은 이 중에서 들깨와 가장 많은 상호작용을 이루고 있다. 또한, 양봉꿀벌은 C집단을 제외한 모든 모듈 집단에서 나타나 허브종으로 보이며, D집단의 메밀과 I집단의 도라지에서 많은 상호작용을 이루고 있다. 즉, 양봉꿀벌은 농업생태계 내의 화분매개네트워크 중에서도 모듈화된 집단끼리의 허브종 역할을 보여주며, 매우 중요한 생태계적 지위를 갖는 것을 알 수 있다(Jung, 2008; Kim et al., 2009; Valido et al., 2019). 농업생태계 화분매개네트워크의 모듈화 분석 결과 양봉꿀벌의 표면적인 중요도뿐만 아니라 기능적인 측면의 중요성을 확인할 수 있었으며, 다른 화분매개자들의 화분매개네트워크 내부 구조적 위치 및 연결 다양성을 볼 수 있다(Valido et al., 2019).

Modularity of the pollination network in the Agricultural Ecosystem. The x-axis represents the pollinator and the y-axis represents the plant. The red rectangles in the center are the communities that emerged through modularity. The frequency of interaction between the pollinator and the plant is displayed darkly in blue. A~I: 9 Modularity.

적 요

여름철 경북과 강원지역 농업생태계의 화분매개네트워크를 조사한 결과 총 2,381개의 상호작용이 나타났으며, 식물 14목 17과 28속 30종에 대해 화분매개자는 4목 52과 129속 154종이 나타났다. 전체 화분매개자 중 양봉꿀벌이 50% 이상 우점하고 있었고 도라지, 들깨, 메밀 등이 식물 종 중에서 가장 많은 참여빈도수를 보였다. 화분매개자 다양성은 딱정벌레 분류군이 34%로 가장 높았으나, 상호작용 참여빈도수는 벌목이 66%로 가장 높게 나타났다. 딱정벌레목과 파리목에서 루드베키아를 선호하는 것이 공통적으로 나타났고, 벌목과 나비목에서는 도라지를 가장 선호한 것으로 나타났다. 딱정벌레목을 제외한 벌목, 파리목, 나비목에서는 도라지를 선호하는 것이 공통점으로 나타났다. 모듈화는 9개의 집단이 나타났으며, 양봉꿀벌이 모듈 간의 연결에 영향을 주는 주요 허브종으로 나타났다. 이번 연구로 여름철 경북과 강원지역 농업생태계 화분매개네트워크의 구조를 확인할 수 있었고, 화분매개자들의 주요 선호도와, 우점 종들을 알 수 있었다. 이 결과는 작물별 필요 화분매개자를 확인할 수 있고, 화분매개서식처 조성을 통한 화분매개자 보호 증식의 기초 자료로 활용될 수 있다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 한국연구재단 이공계대학 중점연구소 과제(과제번호: NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862)에 의해 지원을 받아 수행되었으므로 감사를 드립니다.

References

-

Altieri, M. A. 1999. The ecological role of biodiversity in agroecosystems. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 19-31.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-50019-9.50005-4]

-

Bascompte, J. 2007. Networks in ecology. Basic and Applied Ecology 8: 485-490.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2007.06.003]

-

Bascompte, J. and P. Jordano. 2007. Plant-animal mutualistic networks: The architecture of biodiversity. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 38: 567-593.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095818]

-

Basilio, A. M., D. Medan, J. P. Torretta and N. J. Bartoloni. 2006. A year-long plant-pollinator network. Austral Ecology 31(8): 975-983.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2006.01666.x]

-

Bennett, A. B. and S. Lovell. 2019. Landscape and local site variables differentially influence pollinators and pollination services in urban agricultural sites. Plos One 14(2): e0212034.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212034]

-

Bierzychudek, P. 1981. Pollinator limitation of plant reproductive effort. The American Naturalist 117(5): 838-840.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/283773]

-

Choi, S. W. and C. Jung. 2015. Diversity of insect pollinators in different agricultural crops and wild flowering plants in Korea: literature review. Journal of Apiculture 30: 191-201.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2015.09.30.3.191]

-

Consonni, R., L. R. Cagliani, T. Docimo, A. Romane and P. Ferrazzi. 2013. Perilla frutescens (L.) britton: Honeybee forage and preliminary results on the metabolic profiling by NMR spectroscopyt. Natural Product Research 27: 1743-1748.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2012.751598]

-

Cussans, J., D. Goulson, R. Sanderson, L. Goffe, B. Darvill and J. L. Osborne. 2010. Two bee-pollinated plant species show higher seed production when grown in gardens compared to arable farmland. Plos One 5(7): e11753.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0011753]

-

Danieli-Silva, A., J. M. T. de Souza, A. J. Donatti, R. P. Campos, J. Vicente-Silva, L. Freitas and I. G. Varassin. 2012. Do pollination syndromes cause modularity and predict interactions in a pollination network in tropical high-altitude grasslands? Oikos 121(1): 35-43.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2011.19089.x]

-

Diekotter, T., T. Kadoya, F. peter, V. wolters and F. jauker. 2010. Oilseed rape crops distort plant-pollinator interactions. Journal of Applied Ecology 47(1): 209-214.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01759.x]

-

Dupont, Y. L., K. Trojelsgaard, M. Hagen, M. V. Henriksen, J. M. Olesen, N. M. E. Pedersen and W. D. Kissling. 2014. Spatial structure of an individual-based plant-pollinator network. Oikos 123(11): 1301-1310.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.01426]

-

Ebeling, A., A. Klein, J. Schumacher, W. W. Weisser and T. Tscharntke. 2008. How does plant richness affect pollinator richness and temporal stability of flower visits? Oikos 117(12): 1808-1815.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.16819.x]

-

Garibaldi, L. A., I. Steffan-Dewenter, R. Winfree, M. A. Aizen, R. Bommarco, S. A. Cunningham, C. Kremen, L. G. Carvalheiro, L. D. Harder, O. Afik, I. Bartomeus, F. Benjamin, V. Boreux, D. Cariveau, N. P. Chacoff, J. H. Dudenhoffer, B. M. Freitas, J. Ghazoul, S. Greenleaf, J. Hipolito, A. Holzschuh, B. Howlett, R. Isaacs, S. K. Javorek, C. M. Kennedy, K. M. Krewenka, S. Krishnan, Y. Mandelik, M. M. Mayfield, I. Motzke, T. Munyuli, B. A. Nault, M Otieno, J. Petersen, G. Pisanty, S. G. Potts, R. Rader, T. H. Ricketts, M. Rundlof, C. L. Seymour, C. Schuepp, H. Szentgyorgyi, H. Taki, T. Tscharntke, C. H. Vergara, B. F. Viana, T. C. Wanger, C. Westphal, N. Williams and A. M. Klein. 2013. Wild pollinators enhance fruit set of crops regardless of honey bee abundance. Science 339: 1608-1611.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230200]

-

Ghosh, S. and C. Jung. 2016. Global honeybee colony trend is positively related to crop yields of medium pollination dependence. Journal of Apiculture 31(1): 85-95.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2016.04.31.1.85]

-

Ghosh, S. and C. Jung. 2018. Contribution of insect pollination to nutritional security of minerals and vitamins in Korea. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology 21: 598-602.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aspen.2018.03.014]

-

Gilpin, A., A. J. Denham and D. J. Ayre. 2019. Are there magnet plants in australian ecosystems: Pollinator visits to neighbouring plants are not affected by proximity to mass flowering plants. Basic and Applied Ecology 35: 34-44.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2018.12.003]

-

Gilpin, A., A. J. Denham and D. J. Ayre. 2019. Do mass flowering agricultural species affect the pollination of australian native plants through localised depletion of pollinators or pollinator spillover effects? Ecosystems & Environment 227: 83-94.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2019.03.010]

-

Giulio, M. D., P. T. Edwards and E. Meister. 2001. Enhancing insect diversity in agricultural grasslands: The roles of management and landscape structure. Journal of Applied Ecology 38(2): 310-319.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2664.2001.00605.x]

-

Grab, H., E. J. Blitzer, B. Danforth, G. Loeb and K. Poveda. 2017. Temporally dependent pollinator competition and facilitation with mass flowering crops affects yield in co-blooming crops. Scientific Reports 7: 45296.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45296]

-

Hagen, M. and M. Kraemer. 2010. Agricultural surroundings support flower-visitor networks in an afrotropical rain forest. Biological Conservation 143: 1654-1663.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2010.03.036]

-

Holzchuh, A., C. F. Dormann, T. Tschamtke and I. Steffan-Dewenter. 2011. Expansion of mass-flowering crops leads to transient pollinator dilution and reduced wild plant pollination. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 278(1723): 3444-3451.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2011.0268]

-

Jauker, F., B. Jauker, I. Grass, I. Steffan-Dewenter and V. Wolters. 2019. Partitioning wild bee and hoverfly contributions to plant-pollinator network structure in fragmented habitats. Ecology 100(2): e02569.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.2569]

-

Jennersten, O. 1988. Pollination in Dianthus deltoides (caryophyllaceae): Effects of habitat fragmentation on visitation and seed set. Conservation Biology 2(4): 359-366.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.1988.tb00200.x]

- Jin, L. and S. Jinzheng. 2001. Pollination rates and seed set in Platycodon grandiflorus (jacq.) A. DC. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Normalis Hunanensis 24: 73-75.

- Jung, C. 2008. Economic Value of Honeybee Pollination on Major Fruit and Vegetable Crop in Korea. Kor. J. Apic. 23: 147-152.

-

Jung, C. 2014. Global attention on pollinator diversity and ecosystem service: IPBES and honeybee. Kor. J. Apic. 27: 213-215.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2014.09.29.3.213]

-

Kaiser-Bunbury, C., J. Mougal, A. E. Whittington, T. Valentin, R. Gabriel, J. M. Olesen and N. Bluthgen. 2017. Ecosystem restoration strengthens pollination network resilience and function. Nature 542-223.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature21071]

- Kim, D. W., H. S. Lee and C. Jung. 2009. Comparison of Flower-visiting Hymenopteran Communities from Apple, Pear, Peach and Persimmons Blossoms. Kor. J. Apic. 24: 227-235.

-

Kim, D.W., W. K. Yun and C. Jung. 2014. Residual toxicity of carbaryl and lime sulfur on the European honey bee, Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) and buff-tailed bumble bee, Bombus terrestris(Hymenoptera: Apidae). Kor. J. Apic. 29(4): 341-348.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2014.11.29.4.341]

-

Klein, A.-M., B. E. Vaissiére, J. H. Cane, I. Steffan-Dewenter, S. A. Cunningham, C. Kremen and T. Tscharntke. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 274: 303-313.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721]

-

Kovacs-Hostyanszki, A., S. Haenke, P. Batary, B. Jauker, A. Baldi, T. Tscharntke and A. Holzschuh. 2013. Contrasting effects of mass-flowering crops on bee pollination of hedge plants at different spatial and temporal scales. Ecological Applications 23(8): 1938-1946.

[https://doi.org/10.1890/12-2012.1]

-

Lee, C. Y., S. M. Jeong, C. Jung and M. Burgett. 2016. Acute oral toxicity of neonicotinoid insecticides to four species of honey bee, Apis florea, A. cerana, A. mellifera, and A. dorsata. Journal of Apiculture 31(1): 51-58.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2016.04.31.1.51]

-

Memmott, J. 1999. The structure of a plant-pollinator food web. Ecology Letters 2(5): 276-280.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.1999.00087.x]

-

Naggar, Y. A., G. Codling, J. P. Giesy and A. Safer. 2018. Bee-keeping and the need for pollination from an agricultural perspective in egypt. Bee World 95(4): 107-112.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.2018.1484202]

-

Olesen, J. M. and E. Warncke. 1989. Flowering and seasonal changes in flower sex ratio and frequency of flower visitors in a population of saxifraga hirculus. Ecography 12(1): 21-30.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.1989.tb00818.x]

-

Olesen, J. M., J. Bascompte, H. Elberling and P. Jordano. 2008. Temporal dynamics in a pollination network. Ecology 89(6): 1573-1582.

[https://doi.org/10.1890/07-0451.1]

-

Olesen, J. M., J. Bascompte, Y. L. Dupont and P. Jordano. 2007. The modularity of pollination networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19891.

[https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706375104]

-

Olesen, J. M., L. I. Eskildsen and S. Venkatasamy. 2002. Invasion of pollination networks on oceanic islands: Importance of invader complexes and endemic super generalists. Diversity and Distributions 8(3): 181-192.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-4642.2002.00148.x]

-

Potts, S. G., J. C. Biesmeijer, C. Kremen, P. Neumann, O. Schweiger and W. E. Kunin. 2010. Global pollinator declines: Trends, impacts and drivers. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25: 345-353.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007]

-

Proulx, S. R., D. E. L. Promislow and P. C. Philips. 2005. Network thinking in ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 345-353.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.004]

- R Development Core Team. 2008. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

-

Ricketts, T. H., J. Regetz, I. Steffan-Dewenter, S. A. Cunningham, C. Kremen, A. Bogdanski, B. Gemmill-Herren, S. S. Greenleaf, A. M. Klein, M. M. Mayfield, L. A. Morandin, A. Ochieng and B. F. Viana. 2008. Landscape effects on crop pollination services: Are there general patterns? Ecology Letters 11(5): 499-515.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01157.x]

-

Santamaria, S., A. M. Sanchez, J. Lopez-Angulo, C. Ornosa, I. Mola and A. Escudero. 2018. Landscape effects on pollination networks in mediterranean gypsum islands. Plant Biology 20: 184-194.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12602]

-

Sikora, A., M. Pawel and K. Maria. 2016. Flowering plants preferred by bumblebees (Bombus Latr.) in the botanical garden of medicinal plants in wrocław. Journal of Apicultural Science 60(2): 59-68.

[https://doi.org/10.1515/jas-2016-0017]

-

Topp, E. N. and J. Loos. 2019. Fragmented landscape, fragmented knowledge: A synthesis of renosterveld ecology and conservation. Environmental Conservation 46(2): 171-179.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892918000498]

-

Valido, A., M. C. Rodriguez-Rodriguez and P. Jordano. 2019. Honeybees disrupt the structure and functionality of plant-pollinator networks. Scientific Reports 9: 4711.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41271-5]

-

Wratten, S. D., M. Gillespie, A. Decourtye, E. Mader and N. Desneux. 2012. Pollinator habitat enhancement: Benefits to other ecosystem services. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 159: 112-122.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.06.020]