밀원수 18종의 화밀 분비량과 꽃 특성에 따른 식물-화분매개곤충 상호작용 분석

Abstract

Honey plants provide nectar and pollen to diverse pollinators. The increase in land use has led to the destruction of food sources and habitats for pollinators, significantly threatening the diversity and abundance of pollinators. Measuring the nectar secretion amount from the flower and also from the tree is an important step assessing the qualification of the honey plant. We aim to analyze the flower characteristics and nectar secretion quantities of honey plants distributed near forests and agricultural areas in mid Korea. In addition, the pollinator interaction was analyzed based on the inflorescence characteristics of the 18 plants. The nectar secretion volume per flower was highest in the Firmiana simplex at 1.60±0.13 µL, while it was lowest in the Acer palmatum at 0.02±0.00 µL. The number of pollinator species that participated in the honey plant-pollinator interaction was 46 species, 38 genera and 24 families with 4,405 interactions. From all tree species, either Apis mellifera or Apis cerana was the predominant flower vistor. The analysis of floral characteristics and pollinator interactions revealed that the panicle inflorescence shape, rosaceous corolla shape, and yellow corolla color represented the highest frequency of visits by pollinators. The results explain the possible reason for selective attraction to some honey plants.

Keywords:

Plant-pollinator interaction, Flower trait, Apis mellifera, Apis cerana, Firmiana simplex서 론

밀원수는 양봉꿀벌을 비롯한 다양한 화분매개자에게 먹이를 제공한다 (Baker and Baker, 1975; Baldock, 2020). 이로 인해 다양하고 많은 밀원자원은 꿀벌과 기타 야생 화분매개자에게 매우 중요한 생태적 요소이며 (Isbell et al., 2017; Sutter et al., 2017), 지역 야생 화분매개자의 생태적 가치와 양봉농가의 소득에 영향을 준다 (Mustajarvi et al., 2001; Decourtye et al., 2010). 화분매개자는 꽃가루를 옮겨주는 서비스를 식물에게 제공하고, 이에 대한 보상으로 화밀이나 꽃가루 등 먹이를 획득하게 된다 (Irwin et al., 2010). 밀원수가 풍부하게 되면 그 지역 식물 및 곤충 모두 서로의 개체군 성장과 밀도 상승에 도움을 줄 수 있다 (Futuyma and Mitter, 1996; Sharma et al., 2021). 반대로 밀원 자원의 부족은 양봉 생산성 및 야생 화분매개자의 다양성과 풍부도 감소 요인으로 작용할 수 있다 (Baude et al., 2016; Reilly et al., 2020). 국내 양봉산업에서 주요 양봉산물은 벌꿀이며, 2017년 기준 생산액은 약 1,228억원으로 양봉산업의 약 53.7%를 차지하고 있다 (Lee et al., 2019). 양봉시장은 벌꿀 생산에 높은 의존도를 보이기 때문에 밀원수 연구는 주요 쟁점이라고 할 수 있다 (Hill and Webster, 1995).

밀원수의 다양성은 꿀벌 및 야생 화분매개자의 집단 유지력에 영향을 줄 수 있다 (Timberlake et al., 2019). 국내 식물의 개화시기가 연간 고르게 분포하지 않기 때문에 (Kang and Jang, 2004), 개화식물이 드문 시기에는 화분매개자가 먹이를 구하는 것이 어려울 수 있다 (Wood et al., 2018). 꿀벌과 같이 사육되는 벌들의 경우 인간의 관리에 의해 어느 정도 먹이 수급이 가능하지만, 야생벌을 포함한 많은 화분매개자들은 자연에서 먹이활동을 하기가 쉽지 않다 (Ouvrard et al., 2018). 꽃이 피는 시기가 다양하고 계절마다 개화하여 한 해 동안 연속적으로 먹이를 공급할 수 있게 되면, 꿀벌과 야생 화분매개자들에게 큰 도움이 될 수 있다 (Baden-Bohm et al., 2022).

현재까지 주요 밀원수 중 아까시나무와 밤나무 화밀 특성에 대한 분석 등 밀원수의 중요성에 따라 관련 연구가 진행되고 있다 (Han et al., 2009; Lazaro et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2021a). 그러나 국내 밀원수 자원 500여 종 중 (Jang, 2008; Kim et al., 2020), 연구된 종의 수는 다소 미흡한 실정이며 (Kim et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2021b), 지속적인 연구가 요구되고 있다 (Thomann et al., 2013). 밀원수의 화밀 특성을 분석한 결과는 농경지의 가치와 자연생태계를 강화하기 위한 정보로 사용할 수 있다 (Balzan et al., 2014). 최근 농경지 주변에 밀원수를 보충하여 몇몇 작물의 생산성을 향상시키는 결과가 연구를 통해 증명되었다 (Garibaldi et al., 2014; Albrecht et al., 2020; Son and Jung, 2021). 또한, 늘어난 먹이자원으로 강화된 화분매개자의 생태계 서비스 기능이 향상될 수 있으며, 이는 선순환 작용으로 안정성 있는 자연생태계가 유지될 수 있을 것으로 많은 연구자들은 기대한다 (Wratten et al., 2012; Proesmans et al., 2019; Drobney et al., 2020). 이처럼 밀원수 화밀 분석은 다른 연구로 연계될 수 있는 가능성과 가치가 상당히 높으며, 실제로 많은 연구자들은 연구의 필요성을 이야기하고 있다 (Balzan et al., 2014; Kowalska et al., 2022).

식물과 화분매개자 간 상호작용 정보는 여러 가지 상황에서 중요한 기초자료로 사용될 수 있다. 첫 번째로 생물다양성 보전을 위한 생태적 정보로 제공할 수 있다 (Borchardt et al., 2021; Russo et al., 2022). 어떤 종의 보존 또는 복원을 하기 위해서는 상호작용 관계에 있는 다른 종에 대한 의존도와 생태적 지위를 고려하여 복원과 보전 전략을 수립할 필요가 있기 때문이다 (Biella et al., 2017). 두 번째로 기후변화 등 외부 환경요인에 영향을 받아 나타나는 생물종의 연쇄적 절멸 위험도를 예측하기 위한 데이터로 사용할 수 있다 (Morton and Rafferty, 2017). 최근 발생하는 이상기후 현상과 여러 가지 생태적 교란은 특정 종을 다른 지역으로 이주시키거나 절멸에 이르게 할 수 있다 (Robinson et al., 2009). 이러한 상황이 발생하게 되었을 때, 그 특정 종과 관계를 갖는 다른 종들에게 미칠 영향력을 평가하고, 대책을 마련하기 위한 예측자료가 필요하게 된다 (Gomez-Ruiz and Lancher, 2019). 마지막으로 작물 생산 향상을 위한 지원 연구를 수행하는 데 있어서 핵심자료로 사용할 수 있다 (Giannini et al., 2015; Bansch et al., 2021). 작물을 선호하는 화분매개자에 대한 정보를 이해하여, 해당 종을 강화하고 작물의 생산성 향상을 기대할 수 있다 (Isaacs et al., 2017; Hipolito et al., 2018; Jung and Shin, 2022). 이러한 이유로 연구 수행의 필요성이 요구되지만 국내에서는 관련 연구가 매우 미흡한 실정이다.

그래서 본 연구는 국내 중부지방에 분포하는 밀원수의 화밀 분비 특성을 조사하고, 밀원수의 꽃 특성에 따른 화분매개자 상호작용을 분석하는 것을 목표로 한다. 이를 수행하기 위해 첫째, 밀원수가 생산하는 화밀을 정량적으로 측정하였고, 각 수종의 평균 화밀 분비량을 비교하였다. 둘째, 주요 밀원수에 방화하는 화분매개자들 조사하고, 생물다양성을 분석하였다. 마지막으로 밀원수종별 꽃의 특징에 따라 나타나는 화분매개자를 분석하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 조사지역 및 대상 수종

실험은 경북 안동시 인근 산림과 농업지역에서 2023년 3월부터 8월까지 수행되었다. 실험 대상 종은 경북 안동시에서 흔히 자생하거나 식재 된 목본으로 하였다. 관련 문헌을 참고하여 밀원수를 확인하였고 (Jang, 2008; Ryu and Jang, 2008; Kim et al., 2020), 식물 식별은 도감과 전문가의 자문을 통해 수행하였다 (Chang et al., 2011; Kim and Kim, 2011). 국내 중부지방을 중심으로 산림 및 농경지에 흔하게 분포하는 밀원수 중 9과 14속 18종의 식물을 조사 대상으로 하였다 (Table 1).

2. 화밀 분비량 및 꽃 특성 조사

화밀 분비량 측정은 최소 3개체 이상으로 선택하고 수행하였다. 개화하기 전 꽃봉오리가 형성되면 화분매개자 차단망을 설치하여, 화분매개자로부터의 화밀 손실을 방지하였다. 이후 개화가 시작되면, 차단망을 제거하고, Capillary 튜브 1 μL (Drunnond, USA)로 해당 식물의 화밀 분비샘을 찾아 화밀을 수집하였다. 한 번의 화밀 측정이 끝나면 차단망을 다시 설치하였다. 측정은 하루에 한 번 수행하였으며, 암꽃과 수꽃이 따로 있는 경우 같은 비율로 반복처리 후 평균으로 계산하였다. 나무당 최소 20개에서 최대 50개의 꽃을 대상으로 하였다. Capillary 튜브의 총 길이에서 각 밀원수의 화밀이 채워진 만큼의 길이를 측정하고 부피를 계산하였다. 개화기 동안 조사목의 나무당 평균 화밀 분비량을 추정하기 위해 나무당 평균 개화 수를 조사하였다. 조사목의 화서 및 화관 형태, 화관 색 등 꽃의 특성은 문헌을 통해 조사하였다 (Kim and Kim, 2011). 또한, 밀원수의 평균 흉고 직경 (Diameter at breast height; DBH)과 평균 수고를 측정하여, 나무 특성을 기록하였다.

3. 수종별 화분매개자 조사

각 수종에 따른 방화 화분매개자는 육안 조사로 수행하였다. 조사목의 개화율이 평균 약 30% 이상일 때 오전 8시부터 오후 4시 사이에 무작위로 방문하여 조사를 시작하였다. 꽃에 방화하여 먹이 활동하는 모든 화분매개자들을 대상으로 하였으며, 이 중 주요 화분매개자는 4가지 그룹 (벌목, 파리목, 딱정벌레목, 나비목)으로 정리하였다. 분류 동정이 필요한 경우 포충망으로 포획한 뒤 실험실에 가져와 전문가와 도감 (Park et al., 2012)을 통해 식별하였다. 육안 조사는 개체당 2분간 하였고, 모든 수종은 개화가 시작되고 5반복 이상 진행하였다. 또한, 주간에 조사하였으며, 흐리거나 비가 오는 날은 조사하지 않았다.

4. 자료 분석

각 수종에서 측정된 나무당 평균 꽃 수와 꽃당 평균 화밀 분비량은 정규성을 나타내지 않아 비모수 검정인 Kruskal-Wallis 검정 통해 평균을 비교하였다. 이후, Dunn’s 검정으로 사후검정하였다. 자료 분석 및 통계 분석은 R 프로그램을 통해 수행되었다 (R core team, 2022).

밀원수-화분매개자 상호작용에 참여한 화분매개자 종 생물다양성을 계산하였다. 항목으로는 풍부도 (R)와 종다양성지수 (Shannon-Weiner diversity index, H′)로 하였으며 (Margalef, 1958; Pielou, 1966), 다음과 같은 식을 통해 계산되었다:

| (1) |

풍부도는 전체 종수 (S)에서 1을 뺀 값을 총 개체수 (N)의 자연로그를 취한 값으로 나눈 값이다. 종다양성지수 (H′)는 다음과 같은 식을 통해 계산되었다:

| (2) |

종다양성지수는 i번째 속하는 개체수의 비율 (Pi)에 자연로그를 취한 값과 각 종들의 Pi를 곱하고, 전체 총 합으로 계산된다. Pi는 각 종의 개체수를 전체 개체수로 나눈 값이다.

결 과

1. 화밀 분비량 및 꽃 특성

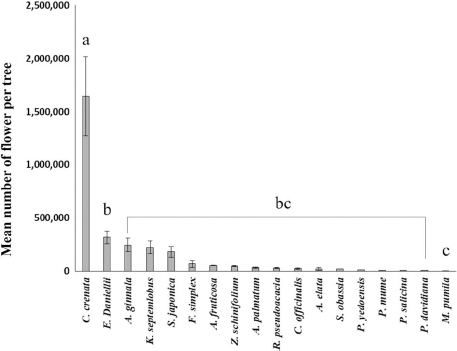

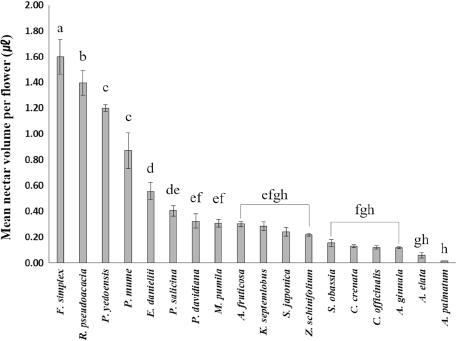

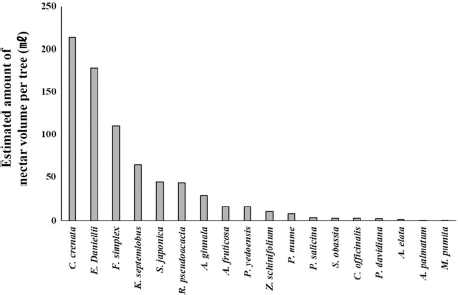

밀원수의 나무당 평균 꽃 수는 밤나무가 1,646,405.0±373,191.8개로 가장 많았고, 쉬나무 319,191.2±58,141.1개가 다음으로 많았으며, 사과나무가 1,324±91.8개로 가장 적었다 (Table 1; Fig. 1.). 꽃당 평균 화밀 분비량은 벽오동나무가 1.60±0.13 μL로 가장 많았으며, 1.40±0.01 μL인 아까시나무가 다음으로 많았고, 단풍나무가 0.02±0.00 μL으로 가장 적었다 (Table 1; Fig. 2.). 꽃당 평균 화밀 분비량과 나무당 평균 꽃 수로 나무당 전체 화밀 분비량을 추정한 결과 밤나무가 약 214.0 mL로 가장 많았으며, 쉬나무가 약 177.8 mL로 두 번째로 많았다 (Fig. 3). 나무당 꽃 수가 가장 적었던 사과나무가 나무당 전체 화밀량이 가장 적게 추정됐고, 꽃 당 평균 화밀 분비량이 가장 적었던 단풍나무가 다음으로 적었다.

Mean numbers of flower per tree for 18 honey plant species commonly distributed in Andong, South Korea. Following the Kruskal-Wallis test (χ²=87.959, df=17, P<0.001), a post hoc analysis was carried out using the Dunn’s test. The error bar indicated the standard error.

Mean nectar volume (μL) per flower for 18 honey plant species measured in 2023, Andong, South Korea. Following the Kruskal-Wallis test (χ²=425.06, df=17, P<0.001), a post hoc analysis was carried out using the Duun’s test. The error bar indicated the standard error.

Estimated amount of nectar per plant (mL) based on the nectar amount of each flower and flower number per tree.

꽃 특성 조사 결과, 화서 (꽃차례)는 원추 (Panicle), 산방 (Corymb), 산형 (Umbel), 총상 (Raceme), 수상 (Spike), 미상 (Catkin) 등 6가지가 확인되었다. 원추를 갖는 형태의 종은 6가지였고, 산방은 4가지, 산형 3가지로 나타났다. 총상과 수상은 각 2가지였고, 미상은 1가지로 나타났다. 화관 형태는 장미형 (Rosaceous), 순형 (Bilabiate), 나비형 (Papillionaceous), 십자형 (Cruciform), 종형 (Campanulate) 등 5가지로 조사됐다. 장미형 화관 형태를 갖는 종은 12가지가 있었으며, 나비형 3가지, 순형과 십자형 및 종형은 각 1가지로 나타났다. 화관 색상의 경우 하얀색을 갖는 종은 7가지, 노란색 4가지, 초록색 3가지로 나타났고, 보라색 2가지와 분홍색과 붉은색은 각 1가지로 나타났다. 꽃 특성 별 화밀 분비량을 비교한 결과 모든 꽃 특성에서 화밀 분비량의 통계적 차이는 나타나지 않았다 (Fig. 4). 화서의 경우 총상에서 평균 약 0.78 μL로 수치상 가장 많은 화밀량을 보였고, 수상 0.59 μL, 원추 0.56 μL, 산방 0.40 μL, 산방 0.16 μL, 미상 0.15 μL 순으로 나타났다. 화관 형태의 경우 나비형이 약 0.79 μL로 수치상 가장 많았으며, 장미형 0.5 μL, 순형 0.17 μL, 종형 0.16 μL, 십자형 0.12 μL 순으로 나타났다. 화관색의 경우 하얀색이 0.60 μL로 수치상 가장 많았으며, 노란색 0.57 μL, 분홍색 0.34 μL, 보라색 0.30 μL, 초록색 0.18 μL, 빨간색 0.08 μL로 나타났다.

Comparison of the mean nectar volume per flower (μL) based on the inflorescence shape (A), corolla shape (B), and colors (C). The Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted to compare the means (A; χ²=5.50, df=5, P=0.3579, B: χ²=3.60, df=4, P=0.4629, C: χ²=7.33, df=5, P=0.1972). The error bar indicated the standard error.

2. 꽃 특성과 밀원수-화분매개자 상호작용 생물다양성

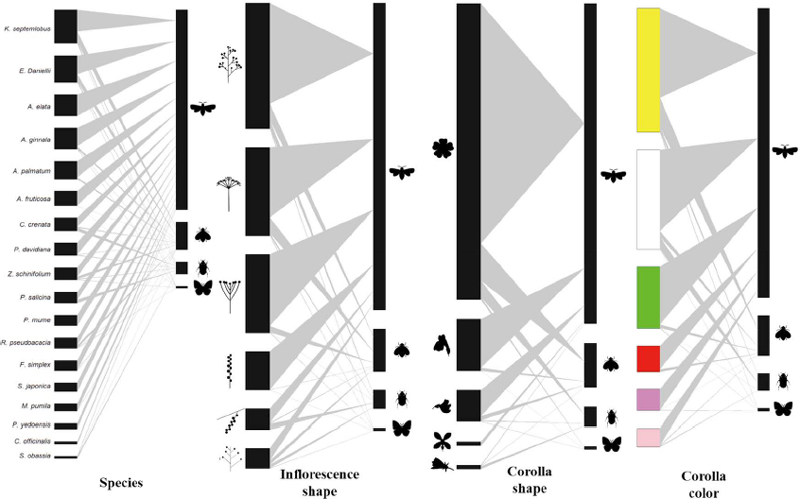

밀원수 18종에서 조사된 화분매개자는 총 4목 24과 38속 46종이고, 조사기간 동안 밀원수에 방문한 화분매개자 빈도수는 4,405개로 나타났다 (Fig. 5). 상호작용 참여 화분매개자를 목별로 구분하면, 벌목이 82.7%로 가장 많은 비율을 차지하였으며, 파리목 11.5%, 딱정벌레목 5.0%, 나비목 0.8% 순으로 나타났다. 상호작용 참여 화분매개자 중 양봉꿀벌 (Apis mellifera)이 41.4%로 절반 가까이 차지하였으며, 재래꿀벌 (Apis cerana)이 11.7%로 두 번째로 많았다. 화분매개자 방문수를 밀원수별로 비교하면, 음나무가 13.9%로 가장 많은 방문 수를 기록하였으며, 11.1%인 쉬나무가 두 번째로 많은 방문 수를 나타냈다. 전체 상호작용에서 나타난 화분매개자의 생물다양성을 분석한 결과 양봉꿀벌이 우점종이었고, 재래꿀벌이 아우점종으로 나타났다 (Table 2). 또한, 풍부도 (R)는 5.36, 종다양성지수 (H′)는 2.36이었다. 각 밀원수별 화분매개자 개체수는 음나무가 611개체로 가장 높았으며, 회화나무가 44개체로 가장 적었다. 풍부도는 쉬나무가 3.71로 가장 높았으며, 두릅나무가 0으로 가장 적었다. 종다양성지수는 쉬나무가 가장 높았으며, 풍부도가 가장 낮았던 두릅나무가 종다양성지수도 가장 낮게 나타났다. 화서 형태에 따른 화분매개자 상호작용 분석 결과 원추 형태가 33.8%로 가장 많은 방문 수를 보였으며, 산형이 23.9% 다음으로 많았다 (Fig. 5). 화관 형태는 장미형이 76.5%로 가장 높았으며, 순형이 13.4%로 두 번째로 높았다. 화관 색상은 노란색이 35.4%로 가장 높았고, 하얀색 28.5%가 다음으로 높았다. 각 밀원수 꽃 특성마다 방문하는 화분매개자의 종별 상호작용 분석 결과 모든 화서 형태, 화관 형태, 화관색에서 꿀벌류가 대부분 우점하였고, 애꽃벌류와 꼬마꽃벌류가 아우점종으로서 나타나는 경향을 보였다 (Fig. 6).

Analysis of pollinator biodiversity among different 18 honey plant species in honey plant-pollinator interaction on Andong, South Korea

Analysis of the honey plant-pollinator interaction and floral characteristics of honey plants commonly distributed in forests and agricultural areas in Andong, South Korea. In all figures, the left side represents honey plant and floral characteristics, while the right side represents the pollinators (from top to bottom: Hymenoptera, Diptera, Coleoptera and Lepidoptera). The width of the black box in the network indicates the frequency of species interaction participation, while the middle gray lines indicate interactions. As the frequency of interactions between species increases, the thickness of the intermediate gray line also increases. The forms of inflorescence shapes are indicated in the following order from top to bottom: panicle, umbel, corymb, spike, catkin, and raceme. The forms of corolla shapes are indicated in the following order from top to bottom: rosaceous, bilabiate, papilionaceous, cruciform, and campanulate.

Analysis of honey plant-pollinator interaction and floral characteristics of honey plants commonly distributed in forests and agricultural areas in Andong, South Korea. In all figures, the left side represents honey plant and floral characteristics, while the right side represents the pollinators. The width of the black box in the network indicates the frequency of species interaction participation, while the middle gray lines indicate interactions. As the frequency of interactions between species increases, the thickness of the intermediate gray line also increases. The forms of inflorescence shapes are indicated in the following order from top to bottom: panicle, umbel, corymb, spike, catkin, and raceme. The forms of corolla shapes are indicated in the following order from top to bottom: rosaceous, bilabiate, papilionaceous, cruciform, and campanulate.

고 찰

밀원수종 18종에 대한 꽃당 화밀 분비량을 조사한 결과 벽오동나무가 가장 많았고, 아까시나무가 두 번째로 많았다. 나무당 평균 화밀 분비량을 추정했을 때에는 밤나무가 가장 많았고, 쉬나무가 다음으로 많았다. 화밀 분비의 절대적인 양도 중요하지만 유리당의 함량과 유리당 중 주요 당 구성 비율이 어떻게 존재하는지도 중요하다 (Jablonski and Koltowski, 2001; Kim et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2023). 당 구성 비율 및 유리당의 양에 따라 벌꿀 전환량이 달라질 수 있기 때문이다 (Gismondi et al., 2018). 밀원수별 화밀의 양봉산업적 가치를 계산하기 위해서는 각 밀원수가 분비하는 화밀 내 유리당에 대한 추가적인 연구가 요구된다. 또한, 본 조사에서 밤나무의 경우 꽃당 평균 화밀량이 0.13±0.01 μL로, 이전 연구 결과인 약 1.8 μL보다 낮았다 (Kim et al., 2017). 쉬나무도 본 연구에서는 0.6±0.07 μL로 이전 연구 결과의 0.58±0.42~2.73±0.63 μL에 포함되기는 하지만 대체적으로 더 낮은 경향을 보였다 (Kim et al., 2014). Han et al. (2009)의 경우 아까시나무의 꽃당 평균 화밀량이 2.20±1.18 μL로 본 연구의 1.4±0.10 μL보다 좀 더 높게 조사됐다. 이러한 이유에는 여러 가지 요인이 결합된 것으로 보이는데, 첫 번째로 국내에서는 현재까지 매년 해가 거듭할수록 벌꿀 생산량이 감소하였는데 (Kim et al., 2021a), 벌꿀 생산량의 감소 원인은 여러 환경 요인에 의한 밀원수의 화밀 분비량 감소이다 (Kim et al., 2022a). 밀원수 화밀 분비량 감소의 주요 원인 중 하나는 기후변화인데, Takkis et al. (2015)에 따르면 기후변화가 그 지역 토착식물의 화밀 분비량에 영향을 미친다고 연구를 통해 발표하였다. Takkis et al. (2018) 역시 기후변화가 식물의 화밀 분비량에 영향을 준다는 것을 실험을 통해 증명하였다. 두 연구 결과 모두 기온이 높아짐에 따라 식물의 화밀 분비량이 낮아지는 경향을 나타냈다. 최근 국내 연간 평균기온은 +0.18℃/10년으로 상승하였으며 (Lee and Kim, 2021), 국내 밀원수도 위와 비슷한 증상이 발생할 수 있을 것으로 추측되고, 더 추가적인 연구도 필요해 보인다. 두 번째로 식물의 나이가 많아지거나 질병에 오염된 경우 화밀 분비량과 유리당 함량에 영향을 줄 수 있다 (Nicolson, 2022). 화밀 분비에는 jasmonate라는 호르몬과 관련이 있는데 (Radhika et al., 2010), 이는 식물체 발달과 병해충으로부터의 방어에 관련된 호르몬이다. 이 호르몬의 분비는 식물의 나이와 병해충으로부터 영향을 받으며 이는 곧 화밀 분비에까지 영향을 주는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Ahmad et al., 2016). 국내 다른 밀원수들의 시간에 따른 연령과 분포 변화에 대한 자세한 연구자료는 없으나 해충의 피해는 지속적으로 발표되고 있다 (Lee et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2009; Ha and Lee, 2016). 각 밀원수를 대상으로 병해충 피해 유무와 화밀 분비량 사이의 관계에 대한 연구는 존재하지 않지만 이전의 관련 연구를 토대로 병해충 피해는 식물의 화밀 생성에 다른 요인과 함께 영향을 줄 가능성이 높다 (Nicolson, 2022). 위와 같은 여러 변수들이 복합적으로 밀원수에 작용하게 되면 밀원수의 과거 화밀 특성 분석자료는 시기와 주변 환경 요인에 따라 현재의 자료와 차이가 있을 것으로 사료된다. 또한, 추후에 밀원수에 따른 화밀 생산량과 병해충 및 나무의 연령에 대한 관련성 연구도 필요할 것이다. 마지막으로 화밀을 수집하는 방법에 따라 꽃당 화밀 분비량을 측정하는 데 차이가 발생할 수 있다고 한다 (Kim et al., 2022b). 차이가 나는 가장 큰 원인은 수분 함량이며, 조사 방법에 따라 수분량이 달라 전체 화밀 추정량이 일정치 않게 나온 것으로 본다. 본 연구에서는 Capillary 튜브로 측정하였고, 다른 문헌에서는 모두 원심분리법을 이용하여 조사된 화밀량에 차이가 있었다 (Kim et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2017).

꽃 특성별 화밀 분비량에는 차이가 있었다. 화서는 총상, 화관의 형태는 나비형, 화관색은 하얀색에서 화밀 분비가 많은 경향이 있었다. 최근까지 꽃의 형태와 화밀 분비량 사이의 관련성은 거의 연구되지 않았다. 다만 화밀 분비량은 토양, 강수량, 기온 등 주변 환경 요인과 그에 따른 호르몬의 변화에 큰 영향을 받는다고 알려져 있기 때문에 (Nicolson, 2022) 꽃의 형태와 화밀 분비량 간 상관성을 규명하는 연구가 필요해 보인다.

밀원수종 18종에서 화서 형태, 화관 형태, 화관 색상 등이 각각 다르게 나타났고, 그에 따른 방문 화분매개자의 개체수와 종 구성도 다르게 나타났다. 화서 형태의 경우 원추가 가장 많은 화분매개자 방문 수를 보였고, 화관 형태는 장미형, 화관 색상은 노란색이 가장 많았다. 꽃의 형태는 화분매개자 유인력에 상당한 영향을 미친다고 알려져 있다 (Harder et al., 2004; Erickson et al., 2022). 일반적으로 화서 형태는 원추나 산형처럼 무한화서에 해당하는 경우 시각적으로 더 풍성해 보여 상대적으로 더 많은 화분매개자에게 선택될 수 있다고 한다 (Harder et al., 2004). 그리고 화관 형태는 화분매개자를 시각적으로 유혹하는 기능과 더불어 꽃가루나 화밀의 배치에도 영향을 주기 때문에, 기능적으로 화분매개자를 가려낼 수 있다 (Kaczorowski et al., 2012). 화서와 화관 형태별 화분매개자의 선호도는 지역적 또는 생물 종 분포 등 여러 생물적 및 환경요인에 따라 다르게 작용할 수 있다 (Gomez et al., 2014). 따라서, 환경 조건과 생물 분포가 다른 지역에서 식물-화분매개 상호작용을 조사하게 된다면, 본 연구의 결과와 달라질 수 있다. 화관 색상의 경우 노란색과 하얀색이 가장 많은 화분매개 방문 수를 나타냈는데, 노란색과 하얀색은 곤충에게 스펙트럼 중 반사율이 높은 영역으로 화분매개자에게 다른 색보다 비교적 선호되는 경향이 있다고 한다 (Lunnau and Maier, 1995; Reverte et al., 2016).

밀원수 18종에서 4가지 화분매개자 그룹 중 벌목이 가장 많은 참여 빈도를 보였고, 파리목, 딱정벌레목, 나비목 순이었다. Son et al. (2019)의 결과보다 벌목의 비율과 벌목 내 양봉꿀벌의 비율이 매우 높아 다른 야생벌과 화분 매개자 그룹이 상대적으로 낮게 나타났다. 이는 최근 발생하는 이상기후와 서식처 파괴 등 다양한 원인으로 인한 야생 화분매개자의 감소와 관련이 있는 것으로 보인다 (Potts et al., 2010; LeBuhn and Luna, 2021). 밀원수별 방문 빈도를 보면 음나무가 화분매개자로부터 가장 높은 방문 수를 나타냈고, 쉬나무가 다음으로 높았다. 음나무와 쉬나무는 국내에서 가장 잘 알려진 주요 밀원수로 대부분의 화분매개자에게 선호도가 높고, 화밀도 많은 것으로 연구되었다 (Han et al., 2010; Truong et al., 2022). 그 밖의 주요 밀원수에 대한 연구는 현재로서 미흡한 실정이며, 국내에서 알려진 주요 밀원 자원의 화밀 특성과 화분매개자에 대 한 연구, 그리고 지속적인 데이터 관리가 필요하다고 판단된다.

적 요

2023년 국내 중부지방의 산림과 농경지에서 일반적으로 분포하는 18종의 밀원수에 대한 화밀 분비량 및 꽃 특성을 조사하였다. 그 결과 밀원수의 나무당 평균 꽃 수는 밤나무가 가장 많았고, 꽃당 화밀 분비량은 벽오동나무가 가장 많았다. 나무당 평균 화밀 분비량을 추정한 결과 밤나무가 가장 많았다. 꽃 특성을 조사한 결과 화서는 원추가 가장 많았고, 화관 형태는 장미형, 화관 색은 하얀색이 가장 많았다. 꽃 특성에 따른 화분매개자 상호작용 방문 빈도수는 화서의 경우 원추가 가장 많았고, 화관 형태는 장미형, 화관 색상은 노란색이 가장 많았다. 화분매개자 그룹별로는 벌목이 가장 많았으며, 파리목이 그 다음으로 많았다. 밀원수별 방문 화분매개자 다양성 분석 결과 대부분의 밀원수에서 우점종은 양봉꿀벌이었고, 화분매개자 개체수가 가장 많은 것은 음나무로 나타났다. 풍부도와 종다양성지수가 가장 높은 밀원수는 쉬나무로 나타났다. 본 연구의 결과를 바탕으로 지역적 밀원수의 중요성과 생태계 상호작용 연구에 필요한 기초자료로 사용될 수 있을 것으로 사료된다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 산림청 (한국임업진흥원) 연구과제 “산림과학기술 연구개발사업 (2021362A00-2123-BD01)” 과제와 이공계대학 중점연구소과제 (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862)의 지원으로 수행되었습니다.

References

-

Ahmad, P., S. Rasool, A. Gul, S. A. Sheikh, N. A. Akram, M. Ashraf, A. M. Kazi and S. Gucel. 2016. Jasmonates: Multifunctional roles in stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 7: 813.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00813]

-

Albrecht, M., D. Kleijn, N. M. Williams, M. Tschumi, B. R. Blaauw, R. Bommarco, A. J. Campbell, M. Dainese, F. A. Drummond, M. H. Entling, D. Ganser, G. A. de Groot, D. Goulson, H. Grab, H. Hamilton, F. Herzog, R. Isaacs, K. Jacot, P. Jeanneret, M. Jonsson, E. Knop, C. Kremen, D. A. Landis, G. M. Loeb, L. Marini, M. McKerchar, L. Morandin, S. C. Pfister, S. G. Potts, M. Rundlof, H, Sardinas, A. Sciligo, C. Thies, T. Tscharntke, E. Venturini, E. Veromann, I. M. G. Vollhardt, F. Wackers, K. Ward, D. B. Westbury, A. Wilby, M. Woltz, S. Wratten and L. Sutter. 2020. The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: a quantitative synthesis. Ecol. Lett. 23(10): 1488-1498.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13576]

-

Baden-Bohm, F., J. Thiele and J. Dauber. 2020. Response of honeybee colony size to flower strips in agricultural landscapes depends on areal proportion, spatial distribution and plant composition. Basic Appl. Ecol. 60: 123-138.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2022.02.005]

-

Baker, H. G. and I. Baker. 1975. Studies of nectar-constitution and pollinator-plant coevolution. pp. 100-140. in Coevolution of Animals, eds, by Gilbert, L.E. and P. H. Raven. University of Texas Press, Austin, TX, USA.

[https://doi.org/10.7560/710313-007]

-

Baldock, K. C. 2020. Opportunities and threats for pollinator conservation in global towns and cities. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 38: 63-71.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2020.01.006]

-

Balzan, M. V., G. Bocci and A. Moonen. 2014. Augmenting flower trait diversity in wildflower strips to optimize the conservation of arthropod functional groups for multiple agroecosystem services. J. Insect Conserv. 18: 713-728.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-014-9680-2]

-

Bansch, S., T. Tscharntke, D. Gabriel and C. Westphal. 2021. Crop pollination services: Complementary resource use by social vs solitary bees facing crops with contrasting flower supply. J. Appl. Ecol. 58(3): 476-485.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13777]

-

Baude, M., W. E. Kunin, N. D. Boatman, S. Conyers, N. Davies, M.A.K. Gillespie, R. D. Morton, S. M. Smart and J. Memmott. 2016. Historical nectar assessment reveals the fall and rise of floral resources in Britain. Nature 530: 85-88.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16532]

-

Biella, P., J. Ollerton, M. Barcella and S. Assini. 2017. Network analysis of phenological units to detect important species in plant-pollinator assemblages: can it inform conservation strategies? Community Ecol. 18: 1-10.

[https://doi.org/10.1556/168.2017.18.1.1]

-

Borchardt, K. E., C. L. Morales, M. A. Aizen and A. L. Toth. 2021. Plant-pollinator conservation from the perspective of systems-ecology. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 47: 154-161.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2021.07.003]

- Chang, C., H. Kim and K. S. Chang. 2011. Illustrated encyclopedia of fauna & flora of Korea, Vol 43. Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Seoul.

-

Decourtye, A., E. Mader and N. Desneus. 2010. Landscape enhancement of floral resources for honey bees in agro-ecosystems. Apidologie 41(3): 264-277.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2010024]

-

Drobney, P., D. L. Larson, J. L. Larson and K. Viste-Sparkman. 2020. Toward improving pollinator habitat: Reconstructing prairies with high forb diversity. Nat. Areas J. 40(3): 252-261.

[https://doi.org/10.3375/043.040.0322]

-

Erickson, E., R. R. Junker, J. G. Ali, N. McCartney, H. M. Patch and C. M. Grozinger. 2022. Complex floral traits shape pollinators attraction to ornamental plants. Ann. Bot. 130: 561-577.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcac082]

-

Futuyma, D. J. and C. Mitter. 1996. Insect-plant interactions: the evolution of component communities. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 351(1345): 1361-1366.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1996.0119]

-

Garibaldi, L. A., L. G. Carvalheiro, S. D. Leonhardt, M. A. Aizen, B. R. Blaauw, R. Isaacs, M. Kuhlmann, D. Kleijn, A. M. Klein, C. Kremen and L. Morandin. 2014. From research to action: enhancing crop yield through wild pollinators. Front. Ecol. Environ. 12(8): 439-447.

[https://doi.org/10.1890/130330]

-

Giannini, T. C., S. Boff, G. D. Cordeiro, E. A. Cartolano Jr., A. K. Veiga, V. L. Imperatriz-Fonseca and A. M. Saraiva. 2015. Crop pollinators in Brazil: a review of reported interactions. Apidologie 46: 209-223.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-014-0316-z]

-

Gismondi, A., S. de Rossi, L. Canuti, S. Novelli, G. D. Marco, L. Fattorini and A. Canini. 2018. From Robinia pseudoacacia L. nectar to Acacia monofloral honey: biochemical changes and variation of biological properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 98(11): 4312-4322.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.8957]

-

Gomez, J. M., F. Perfectti and C. P. Klingenberg. 2014. The role of pollinator diversity in the evolution of corolla-shape integration in a pollination-generalist plant clade. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B-Biol. Sci. 369: 1649.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0257]

-

Gomez-Ruiz, E. P. and T. Lacher. 2019. Climate change, range shifts, and the disruption of a pollinator-plant complex. Sci. Rep. 9(1): 14048.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50059-6]

-

Ha, M. and C. Lee. 2016. Insect pests fauna and the natural enemy insects at eco-friendly and conventional chestnut orchards. JALS 50(4): 17-25.

[https://doi.org/10.14397/jals.2016.50.4.17]

- Han, J., M. S. Kang, S. H. Kim, K. Y. Lee and E. S. Baik. 2009. Flowering, honeybee visiting and nectar secretion characteristics of Robinia pseudoacacia L. in Suwon, Gyeonggi province. J. Apic. 24(3): 147-152.

- Han, J., M. Kang, S. Kim and K. Lee. 2010. Flowering blossom and nectar secretion characteristics of nectar source on Evodia daniellii Hemsl in Suwon. J. Apic. 25(3): 223-227.

-

Harder, L. D., C. Y. Jordan, W. E. Gross and M. B. Routley. 2004. Beyond floricentrism: The pollination function of inflorescences. Plant Spec. Biol. 19(3): 127-218.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-1984.2004.00110.x]

-

Hill, D. B. and T. C. Webster. 1995. Apiculture and forestry (bees and trees). Agrofor. Syst. 29: 313-320.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00704877]

-

Hipolito, J., D. Boscolo and B. F. Viana. 2018. Landscape and crop management strategies to conserve pollination services and increase yields in tropical coffee farms. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 256: 218-225.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2017.09.038]

-

Irwin, R. E., J. L. Bronstein, J. S. Manson and L. Richardson. 2010. Nectar robbing: Ecological and evolutionary perspectives. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 41: 271-292.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120330]

-

Isaacs, R., N. Williams, J. Ellis, T. L. Pitts-Singer, R. Bommarco and M. Vaughan. 2017. Integrated crop pollination: Combining strategies to ensure stable and sustainable yields of pollination-dependent crops. Basic Appl. Ecol. 22: 44-60.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2017.07.003]

-

Isbell, F., P. R. Adler, N. Eisenhauer, D. Fornara, K. Kimmel, C. Kremen, D. K. Letourneau, M. Liebman, H. W. Polley, S. Quijas and M. Scherer-Lorenzen. 2017. Benefits of increasing plant diversity in sustainable agroecosystems. J. Ecol. 105: 871-879.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2745.12789]

- Jablonski, B. and Z. Koltowski. 2001. Nectar secretion and honey potential of honey-plants growing under Poland’s conditions. J. Apic. Sci. 49: 59-63.

- Jang, J. W. 2008. A study on honey plants in Korea (The kind of honey plants in Korea and Around a former Scanning electron microscope form structure of the pollen). Department of Natural Resources, Ph.D. Thesis, Daegu University, p. 134.

- Jung, C. and J. H. Shin. 2022. Evaluation of crop production increase through insect pollination service in Korean agriculture. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 61(1): 229-238.

-

Kaczorowski, R, L., A. R. Seliger, A. C. Gaskett, S. K. Wigsten and R. A. Raguso. 2012. Corolla shape vs. size in flower choice by a nocturnal hawkmoth pollinator. Funct. Ecol. 26: 577-587.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.01982.x]

-

Kang, H. and J. Jang. 2004. Flowering patterns among Angiosperm species in Korea: Diversity and constraints. J. Plant Biol. 47: 348-355.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03030550]

- Kim, J. S. and T. Y. Kim. 2011. Tree of South Korea. Dolbegae, Paju.

-

Kim, K., J. Kim, D. Oh, B. Park, S. Kim, E. Kang, Y. Choi, S. M. Han, M. Lee and D. Kim. 2022a. Survey of the characteristics and current status on acacia honey production in 2021 and 2022. Korea. J. Apic. 37(3): 185-189.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2022.09.37.3.185]

-

Kim, K., M. Lee, Y. Choi, E. Kang, H. Park, B. Park, O. Frunze, J. Kim, S. M. Han, S. O. Woo, S. G. Kim, H. Y. Kim, S. Kim and D. Kim. 2021a. Status and environmental factors of the annual production of acacia honey from the false acacia (Robinia pseudoacacia) in South Korea. J. Apic. 36 (1): 11-16.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2021.04.36.1.11]

-

Kim, M. S., S. H. Kim, J. H. Song and H. S. Kim. 2014. Analysis of secreted nectar volume, sugar and amino acid content in male and female flower of Evodia daniellii Hemsl. J. Korean For. Soc. 103(1): 43-50.

[https://doi.org/10.14578/jkfs.2014.103.1.43]

-

Kim, S. H., A. Lee, H. Y. Kwon, U. Lee and M. S. Kim. 2017. Analysis of flowering and nectar characteristics of major four chestnut cultivars (Castanea spp.). J. Apic. 32(3): 237-246.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2017.09.32.3.237]

- Kim, T., H. Lim, K. Lee, C. Oh, I. H. Lee and H. S. Hwang. 2023. Plus tree selection of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) for tree improvement of timber characteristics. Korea J. Plant Res. 36(1): 91-99.

-

Kim, Y. K., H. W. Yoo, H. Y. Kwon and S. J. Na. 2021b. Estimation of nectar secretion, sugar content and honey production of Prunus mume (Siebold) Siebold & Zucc. J. Apic. 36(3): 141-147.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2021.09.36.3.141]

- Kim, Y. K., J. H. Song, M. S. Park and M. S. Kim. 2020. Analysis of Nectar characteristics of Idesia polycarpa. J. Korean Soc. For. Sci. 109(4): 510-520.

-

Kim, Y. K., S. H. Kim, J. H. Song, J. I. Nam, J. Song and M. S. Kim. 2019. Analysis of secreted nectar volume, sugar and amino acid content in Prunus yedoensis Matsum. and Prunus sargentii Rehder. J. Apic. 34(3): 225-232.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2019.09.34.3.225]

-

Kim, Y., S. Na, H. Kwon and W. Park. 2022b. Comparison of nectar volume and sugar content according to nectar sampling method: Focusing on the capillary tube and centrifuge method. J. Apic. 37(1): 25-34.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2022.04.37.1.25]

-

Kowalska, J., M. Antkowiak and P. Sienkiewicz. 2022. Flower strips and their ecological multifunctionality in agricultural fields. Agriculture 12(9): 1470.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12091470]

-

Lazaro, A., C. Vignolo and L. Santamaria. 2015. Long corollas as nectar barriers in Lonicera implexa: interactions between corolla tube length and nectar volume. Evol. Ecol. 29: 419-435.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-014-9736-5]

-

LeBuhn, G. and J. V. Luna. 2021. Pollinator decline: what do we know about the drivers of solitary bee declines? Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 46: 106-111.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2021.05.004]

- Lee, C. and O. Kim, J. Hwang, J. Choi, Y. Chung and S. M. Lee. 2003. Survey on the forest insect pests in Junsanri-gol, Daewonsa-gol and Georim-gol of Mt. Jiri. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 42(2): 101-110.

-

Lee, J., Y. Jung, K. Choi, I. Kim, Y. Kwon, M. Jeon, S. Shin and W. I. Choi. 2009. Seasonal fluctuation and distribution of Obolodiplosis robiniae (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) Within crown of Robinia pseudoacacia (Fabaceae). Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 48(4): 447-451.

[https://doi.org/10.5656/KSAE.2009.48.4.447]

- Lee, J., Y. Kim, C. Kim. and S. Woo. 2019. The crisis and implications of the beekeeping industry. Agricultural Policy Focus 178: 1-27.

- Lee, W. and H. Kim. 2021. Prediction model of average temperature based on characteristic of urban-space using LSTM and GRU: The case of Wonju city. The Korea Spatial Planning Review 109: 89-104.

-

Lunau, K. and E. J. Maier. 1995. Innate colour preferences of flower visitors. J. Comp. Physiol. A-Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 177: 1-19.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00243394]

- Margalef, R. 1958. Information theory in ecolgy. Int. J. General Syst. 3: 36-71.

-

Morton, E. M. and N. E. Rafferty. 2017. Plant-pollinator interactions under climate change: The use of spatial and temporal transplants. Appl. Plant Sci. 5(6): 1600133.

[https://doi.org/10.3732/apps.1600133]

-

Mustajarvi, K., P. Siikamaki, S. Rytkonen and A. Lammi. 2001. Consequences of plant population size and density for plant-pollinator interactions and plant performance. J. Ecol. 89: 80-87.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2745.2001.00521.x]

-

Nicolson, S. W. 2022. Sweet solutions; nectar chemistry and quality. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 377: 1853.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2021.0163]

-

Ouvrard, P., J. Transon and A. Jacquemart. 2018. Flower-strip agri-environment schemes provide diverse and valuable summer flower resources for pollinating insects. Biodivers. Conserv. 27: 2193-2216.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-018-1531-0]

- Park, K., Y. J. Kwon, J. K. Park, Y. S. Bae, Y. J. Bae, B. Byun, B. Lee, S. Lee, J. Lee, J. Lee, K. Han and H. Han. 2012. Insects of Korea. Geobook. Seoul.

-

Pielou, E. C. 1966. The measurement of diversity in different types of biological collections. J. Theor. Biol. 13: 131-144.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(66)90013-0]

-

Potts, S. G., J. C. Biesmeijer, C. Kremen, P. Neumann, O. Schweigher and W. E. Kunin. 2010. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25(6): 345-353.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2010.01.007]

-

Proesmans, W., D. Bonte, G. Smagghe, I. Meeus, G. Decocq, F. Spicher, A. Kolb, I. Lemke, M. Diekmann, H. H. Bruun, M. Wulf, S. V. D. Berge and K. Verheyen. 2019. Small forest patches as pollinator habitat: oases in an agricultural desert? Landsc. Ecol. 34: 487-501.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-019-00782-2]

-

Radhika, V., C. Kost, W. Boland and M. Heil. 2010. The role of jasmonates in floral nectar secretion. PLoS One 5(2): e9265.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0009265]

- R core team. 2022. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna.

-

Reilly, J. R., D. R. Artz, D. Biddinger, K. Bobiwash, N. K. Boyle, C. Brittain, J. Brokaw, J. W. Campbell, J. Daniels, E. Elle, J. D. Ellis, S. J. Fleisher, J. Gibbs, R. L. Gillespie, K. B. Gundersen, L. Gut, G. Hoffman, N. Joshi, O. Lundin, K. Mason, C. M. McGrady, S. S. Peterson, T. L. Pitts-Singer, S. Rao, N. Rothwell, L. Rowe, K. L. Ward, N. M. Williams, J. K. Wilson, R. lsaacs and R. Winfree. 2020. Crop production in the USA is frequently limited by a lack of pollinators. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 287(1931): 20200922.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.0922]

-

Reverte, S., J. Retana, J. M. Gomez and J. Bosch. 2016. Pollinators show flower colour preferences but flowers with similar colours do not attract similar pollinators. Ann. Bot. 118(2): 249-257.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcw103]

-

Robinson, R. A., H. Q. P. Crick, J. A. Learmonth, I. M. D. Maclean, C. D. Thomas, F. Bairlein, M. C. Forchhammer, C. M. Francis, J. A. Gill, B. J. Godley, J. Harwood, G. C. Hays, B. Huntley, A. M. Hutson, G. J. Pierce, M. M. Rehfisch, D. W. Sims, M. B. Santos, T. H. Sparks, D. A. Stroud and M. E. Visser. 2009. Travelling through a warming world: climate change and migratory species. Endanger. Species Res. 7(2): 87-99.

[https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00095]

-

Russo, L., U. Fitzpatrick, M. Larkin, S. Mullen, E. Power, D. Stanley, C. White, A. O’Rourke and J. C. Stout. 2022. Conserving diversity in Irish plant-pollinator networks. Ecol. Evol. 12(10): e9347.

[https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9347]

- Ryu, J. B. and J. W. Jang. 2008. Newly found honey plants in Korea. J. Apic. 23(3): 221-228.

-

Sharma, G., P. A. Malthankar, V. Mathur and A. Notes. 2021. Insect-plant interactions: A multilayered relationship. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 114(1): 1-16.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/saaa032]

-

Son, M., S. Jung and C. Jung. 2019. Diversity and interaction of pollination network from agricultural ecosystems during summer. J. Apic. 34(3): 197-206.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2019.09.34.3.197]

- Son, M. W. and C. Jung. 2021. Effects of blooming in ground cover on the pollinator network and fruit production in apple orchards. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 60(1): 115-122.

-

Sutter, L., P. Jeanneret, A. M. Bartual, G. Bocci and M. Albrecht. 2017. Enhancing plant diversity in agricultural landscapes promotes both rare bees and dominant crop-pollinating bees through complementary increase in key floral resources. J. Appl. Ecol. 54(6): 1856-1864.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.12907]

-

Takkis, K., T. Tscheulin, P. Tsalkatis and T. Petanidou. 2015. Climate change reduces nectar secretion. Aob Plants 7: plv111.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/aobpla/plv111]

-

Takkis, K., T. Tscheulin and T. Petanidou. 2018. Differential effects of climate warming on the nectar secretion of early- and late-flowering Mediterranean plants. Front. Plant Sci. 9: 874.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00874]

-

Thomann, M., E. Imbert, C. Devaux and P. Cheptou. 2013. Flowering plants under global pollinator decline. Trends Plant Sci. 18(7): 353-359.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2013.04.002]

-

Timberlake, T. P., I. P. Vaughan and J. Memmott. 2019. Phenology of farmland floral resources reveals seasonal gaps in nectar availability for bumblebees. J. Appl. Ecol. 56(7): 1585-1596.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13403]

-

Truong, A., M. Yoo, Y. S. Cho and B. Yoon. 2022. Identification of seasonal honey based on quantitative detection of typical pollen DNA. Appl. Sci. 12(10): 4846.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/app12104846]

-

Wood, T. J., I. Kaplan and Z. Szendrei. 2018. Wild bee pollen diets reveal patterns of seasonal foraging resources for honey bees. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6: 210.

[https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00210]

-

Wratten, S. D., M. Gillespie, A. Decourtye, E. Mader and N. Desneux. 2012. Pollinator habitat enhancement: Benefits to other ecosystem services. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 159: 112-122.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2012.06.020]