고온 환경의 방울토마토 시설하우스에서 환풍장치가 설치된 서양뒤영벌 (Bombus terrestris L.) 봉군의 화분매개효과

Abstract

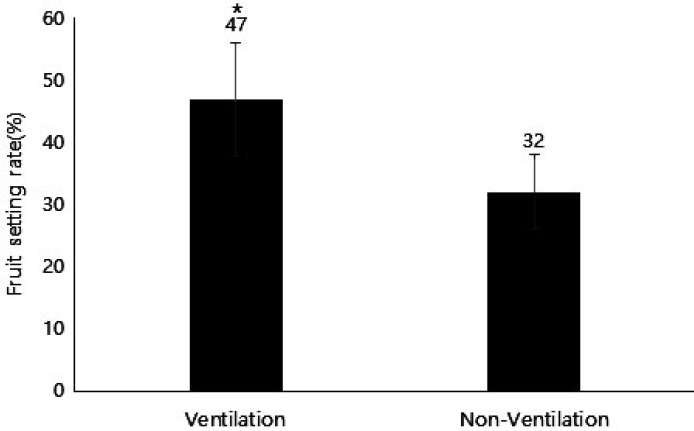

This study compared the internal environment and pollination efficiency of ventilated and non-ventilated bumblebee colonies under high-temperature conditions in August during cherry tomato cultivation. The maximum and minimum temperatures inside the greenhouse were recorded as 32.8±4.4ºC and 30.8±3.3ºC, respectively. The internal temperature of the ventilated colonies reached a maximum of 31.4ºC and a minimum of 27.0ºC, while the non-ventilated colonies reached a maximum of 34.3ºC and a minimum of 27.4ºC. Although there was no significant difference in minimum temperature, the maximum temperature in the ventilated colonies was, on average, 3ºC lower. Additionally, CO2 concentrations in the ventilated colonies ranged from 612.9 ppm to 454.8 ppm, compared to 865.8 ppm to 517.3 ppm in the non-ventilated colonies, showing a maximum difference of 253 ppm. Analysis of hourly bee activity showed that the ventilated colonies exhibited peak activity at 8:00 AM and 7:00 PM, with a total daily activity level 1.2 times higher than the control. Consequently, the fruit set rate was 32% in the non-ventilated colonies, compared to 47% in the ventilated colonies, a 1.5-fold increase. These findings confirm that ventilation improves the pollination efficiency of bumblebees in high-temperature conditions exceeding 35ºC in greenhouses.

Keywords:

Bumblebee, Bombus terrestris L., Pollination, Cherry tomato greenhouse서 론

방울토마토 (Lycopersicon esculentum L.)는 시설하우스 작목 중에서 재배가 꾸준히 증가하고 있는 과채류이다. 최근 건강과 다이어트에 관심이 높아지면서 방울토마토를 사는 소비자가 증가하고 있고, 안전 농산물에 대한 소비자들의 인식변화에 따라 화분매개곤충을 이용하여 친환경적으로 수분하는 토마토의 재배면적이 증가하고 있다 (Yoon et al., 2008). 토마토 재배는 8월 상중순에 파종하는 촉성재배와 저온기에 육묘하는 반촉성재배, 고온기 육묘하는 억제재배 등 다양화로 연중생산이 가능하게 되었다 (RDA, 2009, 2018; Yoon et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2023). 방울토마토 시설억제재배는 온도가 높은 5월쯤에 파종하여 7~8월에 육묘하고, 8월 하순에서 10월 하순까지 수확한다 (Patiguli et al., 2010; RDA, 2017).

토마토꽃은 양성화로 노지 재배에서는 풍매성 (anemophilous)으로 착과가 가능하지만 토마토의 시설재배면적이 늘어남에 따라 뒤영벌 (Bombus spp.)과 같은 화분매개곤충을 사용하게 되었다. 꿀벌 (Apis mellifera)에 비해 뒤영벌은 먹이원으로 화분을 선호하므로 토마토와 같은 무밀작물에 더 효과적으로 사용될 수 있다 (Plowright and Pendrel, 1977; Sutcliffe and Plowright, 1990; Lee and Yoon, 2017). 특히 토마토의 약 (수술)은 옥수수 모양으로 생겨 화분은 관 모양으로 된 내부에서 형성되어 바깥쪽으로 나오게 되어 있어 진동수분을 하는 뒤영벌이 가장 효과적이다 (Buchmann and Hurley, 1978; Heinrich, 1979; Lee et al., 2012). 서양뒤영벌 (Bombus terestris L.)은 성공적으로 상업화된 화분매개곤충으로 한 해 200만 봉군이 화분매개용으로 생산되고 있으며 (RDA, 2023), 유럽에서는 1987년부터 토마토의 대부분의 시설재배농가에서 화분매개자로 사용하고 있다 (Koidae, 1994; Likeda and Tadauchi, 1995; Dogterom et al., 1998; Velthuis and Van Doorn, 2006).

고온 환경은 뒤영벌과 같은 사회성 꿀벌과 곤충의 방화활동에 영향을 준다. 특히 꿀벌이나 뒤영벌은 봉군 내부의 유충을 안정적으로 양육하기 위해 30℃ 내외로 온도를 유지시키는데, 특히 서양뒤영벌의 경우 온도가 30℃가 넘으면 방화활동이 적어지기 시작하며 32℃에서는 방화활동이 제한되고 뒤영벌이 봉군의 환기를 위해 날개를 떠는 선풍행동 (fanning behavior)이 증가한다 (Heinrich, 1979; Vogt, 1986a; Weidenmüller et al., 2002; Couvillon et al., 2010). 반대로 외기 온도가 5℃ 미만의 추위에서 꿀벌은 봉군을 보호하기 위해 월동봉구 (winter cluster)를 형성하여 추위에 대항한다 (Doke et al., 2015). 벌 대신 인위적인 방법을 통한 봉군의 온도관리는 벌의 활동성을 증대시키고 효과적인 활동을 이끌어 낼 수 있다 (Lee et al., 2022). 특히 30℃ 이상 고온 비닐하우스 환경에서 뒤영벌의 봉군에 환풍장치를 통해 선풍행동을 감소시키고 방화활동을 증가시킬 수 있다 (Lee and Yoon, 2017).

국내의 촉성, 반촉성 및 노지억제재배 토마토는 늦어도 8월 초순이면 수확이 모두 끝나서 8월부터는 토마토의 품귀현상이 나타난다 (RDA, 2017). 이 시기에 재배하는 토마토의 출하 단가가 높아지기 때문에, 최근 고온기에 시설재배하는 방울토마토 농가가 늘어나는 추세이다 (RDA, 2020). 그러나 고온으로 인해 토마토의 꽃가루의 생성이나 발아가 잘 일어나지 않을 뿐만 아니라 서양뒤영벌의 활동도 적어져 이 시기에 토마토 재배자들은 호르몬제를 사용하여 착과시키고 있는 실정이다 (RDA, 2023).

따라서 본 연구는 여름철 고온 시설재배 토마토에서 서양뒤영벌의 이용가능성을 확인하기 위하여, 뒤영벌 봉군에 환풍장치를 설치하고 벌의 활동성과 화분매개효과를 검증하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 시험포장 및 시험곤충

여름 토마토 시설하우스 재배지는 충청남도 논산시 성동면 개척리 소재 (36°10ʹ52ʺN, 127°01ʹ28ʺE), 6동 (660 m2/동, 100 m/길이/동)에서 2021년 8월 10일부터 2021년 8월 20일까지 실험을 진행하였다. 방울토마토는 요요 품종을 사용하였다. 고온에서 서양뒤영벌의 화분매개활동을 확인하기 위하여, 국립농업과학원 양봉생태과에서 26℃, RH 65%, 암조건에서 계대사육된 서양뒤영벌 (Bombus terrestris) 16세대 봉군을 사용하였다 (Yoon et al., 2004). 실험에 사용된 뒤영벌 봉군 크기는 여왕벌 1마리에 일벌 120마리로 설정하였다.

2. 시험구 설치

환풍장치가 봉군에 미치는 효과를 확인하기 위하여, 3개 동에는 환풍장치를 설치한 봉군을 넣어 조사하였고, 다른 3개 동에는 무설치 봉군을 설치하였다. 환풍장치는 Lee and Yoon (2017) 문헌을 참고하여 제작하였다. 서양뒤영벌 벌통의 측면에 70 mm PC용 쿨링팬 (Zalman, Korea), 벌통 덮개 상단에 100 mm 쿨링팬을 설치하였다. 쿨링팬을 측면에 설치하여 외부공기를 흡입시키고, 벌통 위쪽 덮개부분의 쿨링팬을 통하여 봉군 내부의 더운 공기를 배출하는 구조로 봉군 내부를 환기시켰다. 쿨링팬은 벌통 내부 온도가 32℃ 이상이거나 CO2 농도가 1,000 ppm 이상이 될 때 가동이 되도록 별도의 임베디드시스템 (JMP system, Hanam-si, Korea)을 제작하여 사용하였다.

3. 시설온실의 온도와 봉군 내부 환경 및 시험곤충 활동량 조사

방울토마토 시설하우스에 설치된 봉군 내부 환경을 조사하기 위해 자체제작 통합센서 (JMP system, Seoul, Korea)를 설치하여 2021년 8월 10일부터 2021년 8월 20일까지 10일 동안 봉군 내부 온도, 습도와 이산화탄소를 1시간 간격으로 측정하였다. 이미지 기반 벌 활동량 측정장치 (Lee et al., 2020)를 이용하여 일 평균 소문출입량 (Bee traffic)을 측정하고 이를 기반으로 활동량을 계산하였다. 시설하우스 온도는 기상환경정보 수집장치 (Illuminance UV recorder TR-74Ui; T&D Co.; Matsumoto, Nagano, Japan)를 비닐하우스의 입구에서 50 m 되는 지점에 설치하여 20분 간격으로 측정되게 설정하였다.

4. 벌통 환풍 처리에 따른 화분매개효과

벌통 환풍 처리에 따른 화분매개효과를 조사하기 위해 토마토의 착과율과 수확된 과실의 품질을 조사하였다. 토마토 착과율 조사는 뒤영벌 투입 후 15일이 지난 8월 25일에 각 비닐하우스에서 입구에서부터 10 m씩 무작위로 10주씩 총 100주를 선정하고 각 주 수별로 꽃 10개씩 선정하여 수정된 꽃의 비율로 나타내었다. 수정된 꽃의 판단은 서양뒤영벌이 토마토 꽃을 방문한 흔적인 방화흔 (Bite mark)의 유무로 정하였다 (Lee et al., 2009). 과실품질은 뒤영벌 방사 후 35일이 지난 9월 15일 방울토마토를 무작위로 시험구당 100개를 수확하고, 각 수확된 방울토마토의 무게, 장경, 단경, 당도를 측정하였다. 무게는 전자저울 (CB-3000, AND, Seoul, Korea)을 사용하여 조사하였고, 당도는 거즈로 착즙하여 디지털 당도계 (PR-32α, Atago, Tokyo, Japan)를 이용하여 측정하였다. 장경, 단경은 토마토를 절개하여 Vernier calipers를 사용하여 길이를 측정하였다. 장경은 꼭지 부분부터 밑부분까지의 가장 긴 부분을 쟀고, 단경은 방울토마토의 가장 넓은 부분, 폭을 조사하였다.

5. 통계분석

벌의 활동량에 대한 분석은 R program을 통하여 계산되었다 (R Core Team, 2021). 그룹별 시간의 평균 벌의 봉군출입수를 계산하기 위해 group_by와 summarise 함수를 사용하였다. 각 그룹의 시간 단위 누적 출입수를 계산하기 위해 cumsum 함수를 사용하였다. 각 그룹의 10일간 매시간의 누적 출입수의 그래프를 pracma 패키지의 trapz 함수를 사용하여 면적으로 계산 후 시험구와 대조구의 활동성을 비교하였다 (Borchers, 2019). 시설하우스 내부 환경과 벌의 봉군 출입수 간의 관계를 확인하기 위하여 pearson 상관분석을 실시하였다. 무처리구와 처리구간 환경요인 (온도, 습도, CO2 농도), 토마토 착과율과 수확물의 평균 비교는 정규성 검정 후 정규분포를 만족한 데이터셋을 기준으로 t-test로 비교분석하였다. 통계분석 패키지는 SPSS PASW 22.0 for windows (IBM, USA)를 사용하였다.

결론 및 고찰

1. 고온 환경인 시설하우스에서 서양뒤영벌 봉군 내부의 환풍 처리에 따른 일별 환경 변화

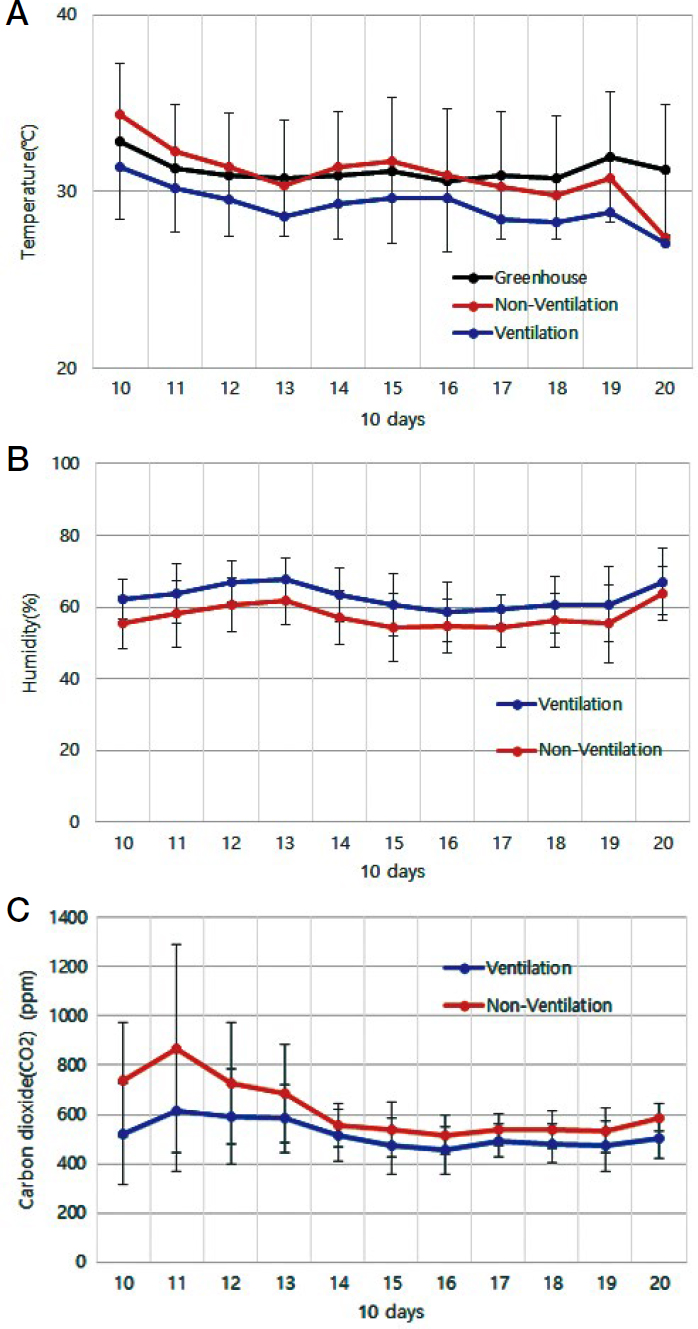

방울토마토 하우스 내부 온도 변화를 10일 동안 측정한 결과, 평균 31.2℃, 최고온도 32.8±4.4℃, 최저온도 30.8±3.3℃로 나타났다 (Fig. 1-A). 날짜별 서양뒤영벌 봉군 내부의 온도 변화를 조사한 결과, 환풍설치 봉군의 평균온도 29.1±1.1℃, 최고온도 34.3±1.3℃, 최저온도 25.2±1.4℃이고, 무설치 봉군은 평균온도 31.0±1.6℃, 최고온도 37.6±1.0℃, 최저온도 26.3±1.5℃로 최저온도는 차이가 없지만 (t-test t19.862=-1.672, p=0.110) 최고온도는 3.3℃ 정도 유의미한 차이가 있었다 (t18.954=-6.550, p=0.0001; Fig. 1-A). 환풍 처리 시 뒤영벌 봉군 온도는 외기보다 평균 2.1℃ 낮게 유지되었다. 뒤영벌은 봉군 내부 온도를 약 28~32℃에 유지될 수 있도록 일벌의 수와 유충의 양육을 조절한다고 보고하였고 (Vogt, 1986a), 33℃ 이상이면 방화활동이 감소하는 경향이 있다고 알려져 있다 (Couvillon et al., 2010). 따라서 고온 환경에서 환풍설치나 무설치나 모두 봉군 내부 온도가 33℃ 이상 올라가기 때문에 화분매개활동에 지장을 받을 것으로 생각된다. 그러나 환풍 처리구와 무처리구의 온도범위를 고려할 때 환풍설치구가 무설치구보다 화분매개활동에 유리할 것으로 예상된다.

Variations by date in the internal environmental conditions of the cherry tomato greenhouse and bumblebee colonies. (A): Temperature variations of the greenhouse, non-ventilation colonies, and ventilation colonies. (B): Humidity variations of the non-ventilation and ventilation bumblebee colonies. (C): Carbon dioxide variations of the non-ventilation and ventilation bumblebee colonies.

날짜별 서양뒤영벌 봉군 내부의 습도 변화양상은 온도 변화양상의 반대로 나타났다. 이는 봉군 내부 온도가 높으면 반대로 상대습도가 낮은 음의 상관관계를 나타낸다는 Hou et al. (2016)의 보고와 유사하였다 (Fig. 1-B).

환풍 처리에 따른 봉군 내부의 CO2 농도는 환풍설치 봉군 내부와 무설치 봉군 내부가 처음 4일 동안은 최대 493 ppm까지 차이가 있었고, 그 이후 60~160 ppm으로 큰 차이는 나지 않았지만, 환풍설치 봉군의 CO2 농도는 지속적으로 낮은 ppm을 보였다 (Fig. 1-C). 뒤영벌 일벌은 33℃ 이상의 고온 환경에서 봉군 내부의 온도 감소와 CO2 농도 감소 (Weidenmüller et al., 2002)를 위해 선풍행동을 하는 것으로 보고되었다 (Heinrich, 1979; Seeley and Heinrich, 1981; Barrow and Pickard, 1985; Vogt, 1986a, 1986b; Couvillon et al., 2010). 이번 결과는 환풍 처리 시 고온에서 CO2의 농도를 낮춰주므로 선풍행동보다는 화분매개활동이 증가될 것이라고 예상된다.

2. 고온 환경인 시설하우스에서 서양뒤영벌 봉군 내부의 환풍 처리에 따른 시간별 환경 분석

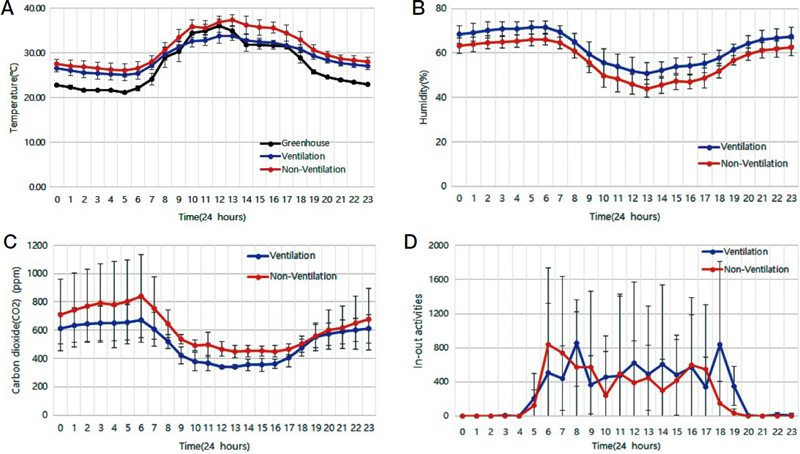

일주시간에 따른 방울토마토 온실의 평균온도를 측정한 결과, 12시에 36.2±1.5℃로 최고온도를 보였고 그 시간에 환풍설치 봉군 내부 평균온도가 가장 낮은 온도를 보였다 (Fig. 2-A). 시간별로 평균 봉군 내부 온도 변화를 10일 동안 조사한 결과, 0시부터 8시, 19시부터 23시까지는 환풍설치 봉군과 무설치 봉군에서 차이가 크게 나진 않았지만 무설치 봉군보다는 환풍설치 봉군이 낮은 온도를 보였다. 평균적으로는 약 1.9℃ 차이를 보였다. 환풍설치 봉군의 최저 봉군 내부 온도는 5시 25.1℃, 최고온도는 12시 33.9℃이고, 일반 벌통의 최저 봉군 내부 온도는 5시에 26.2℃, 최고온도는 13시에 37.4℃로 나타났다. 환풍설치 봉군과 무설치 봉군의 내부 온도는 9시부터 차이가 벌어지기 시작하여 가장 고온인 12시부터 16시까지 범위에서는 3~4℃ 차이를 보였다 (Fig. 2-A).

Diurnal variations in the internal environmental conditions of the cherry tomato greenhouse and bumblebee colonies. (A): Temperature variations of the greenhouse, non-ventilation colonies, and ventilation colonies. (B): Humidity variations of the non-ventilation and ventilation bumblebee colonies. (C): Carbon dioxide variations of the non-ventilation and ventilation bumblebee colonies. (D): In-out activities of the non-ventilation and ventilation colonies.

10일 동안 시간별로 봉군 내부 상대습도 평균값을 비교해 본 결과, 무설치 봉군 내부 습도는 환풍설치 봉군보다 낮은 습도를 보였다. 무설치 봉군과 환풍설치 봉군의 습도 평균차는 조사된 시간 동안 대체로 약 6% 정도로 나타났다 (Fig. 2-B).

환풍설치 봉군과 무설치 봉군의 봉군 내부의 이산화탄소의 변화를 관찰한 결과, 모든 시간대에서 환풍설치 봉군의 CO2가 더 낮은 농도를 보였다. 두 그룹 모두 오전에 CO2의 농도가 증가하다가 낮에는 감소하고 다시 오후부터 증가하는 패턴을 나타내었다. 환풍설치 봉군 CO2 최고농도는 6시 670.2 ppm이고, 최저농도는 13시 342.0 ppm을 보였다. 무설치 봉군 최고 CO2 농도는 6시 840 ppm이고, 최저농도는 13시 449.9 ppm으로 나타났다 (Fig. 2-C).

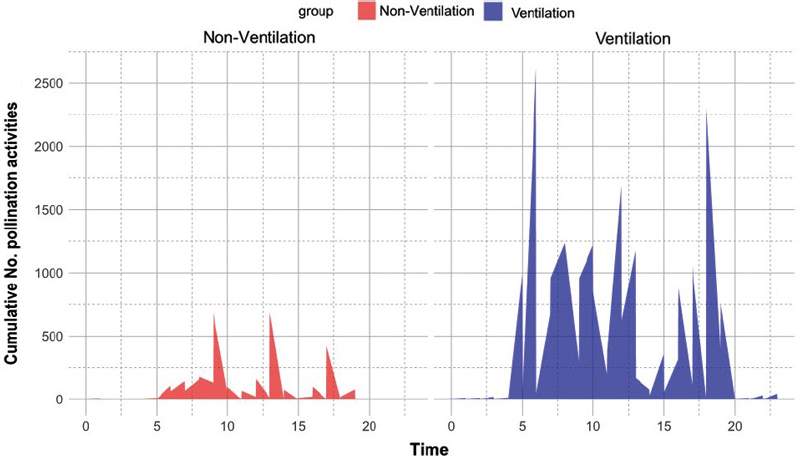

시간별 봉군 출입수의 평균을 조사한 결과, 환풍 처리 봉군은 8시에 높은 출입수를 보였고 19시에 다시 활동이 활발해지는 반면, 무설치 봉군은 6시에 가장 많은 봉군 출입수를 나타낸 이후로 감소하다가 16시경 다시 많아지다가 다시 감소하는 경향이었다 (Fig. 2-D).

봉군 내부가 고온이 되면 벌들의 대사가 증가함에 따라 봉군의 CO2 농도가 증가하게 되는데, 이때 일벌들은 외기 산소를 공급하기 위하여 선풍행동을 한다 (Heinrich, 1979; Weidenmüller et al., 2002; Lee and Yoon, 2017). 일부 뒤영벌 (B. bifarius) 중에는 내역봉 중 선풍행동 같은 봉군 내부의 환경을 조절하는 일벌의 수가 많아지면 외역이나, 유충 사육하는 일벌의 수가 줄어들기도 한다고 알려져 있다 (O’Donnell et al., 2000; Lee and Yoon, 2017).

이번 결과는 봉군 내부 온도와 CO2 농도는 반대의 패턴을 보였다 (person correlation r=-0.945, p=0.0001; Table 1). 이러한 결과는 봉군 내부의 온도가 올라가면서 선풍행동을 하는 벌의 수가 늘어나 봉군 내부의 CO2 농도가 낮아지기 때문이었을 것으로 생각된다. 또한 무설치 봉군의 경우 봉군 내 CO2 농도와 벌의 소문출입수 간 상관을 나타냈다 (r=0.579, p=0.030; Table 1). 이는 벌의 선풍행동으로 인해 CO2의 농도가 낮을 때 벌의 소문출입행동이 적어지고, 반대로 선풍행동의 감소로 CO2의 농도가 높아지면 벌의 소문출입행동이 증가하기 때문으로 생각된다. 환풍설치 봉군의 경우 역시 봉군 온도와 CO2는 부의 상관이 있었다 (r=-0.983, p=0.0001; Table 1). 이는 환풍설치구의 FAN의 작동조건이 봉군 온도가 32℃ 이상일 때 작동하는 것으로 설정되어 봉군 내부 온도가 오르면 FAN이 작동되어 CO2의 농도를 낮추었기 때문으로 설명될 수 있다. 다만 흥미로운 점은 CO2 농도와 벌의 소문출입수 간 상관이 없는 것으로 나타났다는 점인데 (p=0.940; Table 1), 이는 온도에 따라 FAN이 작동하여 환풍이 됨으로 인해 CO2 농도에 상관없이 벌이 활동을 했다는 것으로 해석할 수 있다. 달리 말하면 환풍 처리가 벌의 선풍행동을 대체하여 벌의 활동을 비교적 안정적으로 유지시켰다고 할 수 있는데, 실제로 환풍설치 봉군과 무처리 봉군의 누적활동량을 비교한 결과 (Fig. 3), 환풍설치 봉군은 75258.5이고, 일반 봉군은 63453.5로 환풍설치 봉군이 화분매개활동 수가 1.2배 더 많은 것으로 확인되었다.

Analysis of the correlation between CO2, colony temperature, and bee traffic in a high-temperature tomato greenhouse

3. 고온 시설 토마토 재배 환경에서 환풍 처리 봉군의 화분매개효과

고온 토마토 재배 환경에서 환풍설치 봉군과 무설치 봉군의 화분매개효과를 조사하였다. 착과율을 비교한 결과 무설치 봉군은 32.0±6.0%의 착과율을 보였으며, 환풍설치 봉군은 46.9±9.1%로 무설치 봉군보다 1.5배 더 높은 착과율을 보였다 (t-test, t11.889=3.686, p=0.003; Fig. 4).

Analysis of fruit setting rate in ventilation and non-ventilation bumblebee colonies. Statistical Analysis: t-test t11.889=3.686, p=0.003.

수확물을 비교한 결과, 환풍설치 봉군의 무게는 12.9±3.2 g이고, 무설치 봉군은 12.4±3.1 g으로 다소 차이가 나지 않았다 (t-test, t57.987=0.702, p=0.486). 장경과 단경 길이는 환풍설치 봉군이 각각 42.4±3.9 mm, 22.1±2.6 mm이고, 무설치 봉군이 41.6±3.9 mm, 21.7±2.3 mm로 통계적인 차이는 없었다 (t-test. t58=0.804, p=0.425, t57.228=0.628, p=0.533). 다만 당도는 무설치 봉군이 약 1.15 brix 높은 것으로 나타났다 (t-test. t12.429=3.555, p=0.004, Table 2). Lee and Yoon (2017)은 6월 채종용 양파 비닐하우스에서 환풍설치 뒤영벌 봉군과 무설치 봉군의 화구수정률과 수확된 종자 수 비교한 결과 환풍설치 봉군이 무설치 봉군보다 1.1~1.4배 높았지만, 종자 품질의 차이는 없는 것으로 보고하였는데 이번 결과와 유사하였다.

Comparison of merchatable quality percentage of cherry tomatoes between ventilation and non-ventilation bumblebee colonies.

이러한 결과들을 종합하면, 고온 토마토 재배 환경에서 뒤영벌 봉군에 환풍설치할 경우 봉군 내부의 온도와 CO2 농도가 무설치 봉군보다 낮아지고, 서양뒤영벌의 활동을 높여 화분매개효과를 높일 수 있었다. 특히 본 연구의 결과는 인공수분에 의존해왔던 여름 토마토의 생산을 향상시켜 농가의 소득향상에 도움을 줄 수 있다는 데 가치가 있다. 그럼에도 이 기술의 실용성 측면에서, 고온 상황에서 환풍설치 뒤영벌이 얼마나 오래 쓸 수 있는지, 그리고 기존의 인공수분에 비해 어느 정도의 경제성이 있는지에 대한 결과가 부족하다. 따라서 향후 환풍설치 뒤영벌 봉군의 사용과 기존 인공수분과의 착과율과 수확물 품질 비교 연구가 필요할 것으로 판단된다. 아울러 이번 연구는 고온 상황에서 환풍을 통한 봉군 내부 환경 개선이 목적이었다고 한다면 동계작물에서 봉군 내부 온도를 안정적으로 유지시키기 위한 보온장치에 대한 연구로도 확장할 수 있다 (Lee et al., 2022).

이 결과를 바탕으로 벌통 내부를 뒤영벌이 생존하기 좋은 조건으로 만들어 화분매개의 능력을 향상시키는 ‘스마트 벌통’과 같은 형태로 발전된다면 향후 시설 농작물에서 다양한 작물의 생산성 향상을 기대할 수 있을 것이다.

적 요

방울토마토 8월의 고온 시설재배 환경에서 환풍설치 봉군과 무설치 봉군의 내부 환경 차이와 화분매개효과를 비교하였다. 비닐하우스 내부 낮 최고온도 32.9±4.4℃, 최저온도는 30.8±3.3℃로 확인되었다. 일별 봉군 내부 온도 변화 결과는 환풍설치 봉군은 최고온도 31.4℃, 최저온도는 27.0℃이고 무설치 봉군의 최고온도는 34.3℃, 최저온도 27.4℃로 최저온도는 차이가 없지만 최고온도는 평균 3℃ 정도 차이가 나타났다. 봉군 내부 CO2 농도 범위는 612.9 ppm에서 454.8 ppm으로 나타났고, 무설치 봉군은 865.8 ppm에서 517.3 ppm로 환풍설치 봉군이 최대 253 ppm 낮은 값을 보였다. 시간별 봉군 출입수의 평균은 환풍설치 봉군은 오전 8시에 높은 출입수를 보였고 19시에 다시 활동하는 결과를 보였다. 각 시간대의 누적 출입수를 비교한 결과 환풍설치 봉군이 활동 수가 무설치 봉군보다 1.2배 더 많은 것으로 나타났다. 착과율은 무설치 봉군이 32%, 환풍설치 봉군이 47%로 1.5배 더 높은 착과율을 보였다. 이러한 결과를 볼 때 비닐하우스 내부가 35℃ 이상의 고온 조건에서 뒤영벌의 환풍설치를 통한 화분매개효과 향상은 인정되었다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 2024년도 농촌진흥청 국립농업과학원 전문 연구원 과정 지원사업과 농촌진흥청 연구사업 (주관과제명: 주요 과채류에 대한 화분매개곤충 기술적용 및 실증, 세부과제번호: RS2021-RD009627)을 수행하는 과정에서 얻은 결과를 바탕으로 작성되었습니다.

References

-

Barrow, D. A. and R. S. Pickard. 1985. Larval temperature in brood clumps of Bombus-Pascuorum (Scop). J. Apic. Res. 24: 69-75.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1985.11100651]

- Borchers, H. W. 2019. Package ‘pracma’. Practical numerical math functions, version 2.2.5.

-

Buchmann, S. L. and J. P. Hurley. 1978. A biophysical model for buzz pollination in angiosperms. J. Theor. Biol. 72: 639-657.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(78)90277-1]

-

Couvillon, M. J., G. Fitzpatrick and A. Dornhaus. 2010. Ambient air temperature does not predict body size of foragers in bumble bees (Bombus impatiens). Psyche 2010: 536430.

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/536430]

-

Dogterom, M. N. H., J. A. Matteoni and R. C. Plowright. 1998. Pollination of greenhouse tomatoes by the North American Bombus bosnesenskii (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 91: 71-75.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/91.1.71]

-

Doke, M. A., M. Frazier and C. M. Grozinger. 2015. Overwintering honey bees biology and management. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 10: 185-193.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2015.05.014]

- Heinrich, B. 1979. Bumblebee economics. Harvard University. Press; Cambridge, MA, USA.

-

Hou, C. S., B. B. Li, S. Deng and Q. Y. Diao. 2016. Effects of Varroa destructor on temperature and humidity conditions and expression of energy metabolism genes in infested honeybee colonies. Genet. Mol. Res. 15(3): gmr.15038997.

[https://doi.org/10.4238/gmr.15038997]

- Koidae, D. 1994. Effects of pollination and caution point by Cultivation and Horticulture pp. 96-99.

-

Lee, H. Y., H. B. Jeong, J. G. Lee, I. D. Hwang, D. H. Kwon and Y. K. Ahn. 2023. Growth, Yield, and Leaf-macronutrient Content of Grafted Cherry Tomatoes as Influenced by Rootstocks in Semi-forcing Hydroponics. J. Bio-Env. Con. 32: 40-47.

[https://doi.org/10.12791/KSBEC.2023.32.1.040]

-

Lee, K. Y. and H. J. Yoon. 2017. The Pollination Properties and Pollination Efficiency of Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris L.) Relation to Colony Ventilation under High Temperature Condition in a Greenhouse. J. Apic. 32(3): 205-221.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2017.09.32.3.205]

-

Lee, K. Y., K. Sankar, Y. B. Lee and H. J. Yoon. 2022. Effect of thermal insulation of honeybee (Apis mallifera L.) hive on strawberry pollination in greenhouse. J. Apic. 37: 207-216.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2022.09.37.3.207]

-

Lee, K. Y., S. Choi, J. Lee and H. J. Yoon. 2020. Development of imaging-based honeybee traffic measurement system and its application to crop pollination. J. Apic. 35: 233-243.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2020.11.35.4.233]

-

Lee, S. B., I. G. Park, I. H. Park, H. J. Yoon, K. Y. Lee, S. J. Jang, Y. Chae, H. J. Yong and B. R. Choi. 2009. Lifespan Elongation of Bombus terrestris and Economic Effect by Regular Pollen Supplement to Its Hives Released on Beefsteak-tomato Varieties. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 48(3): 393-401.

[https://doi.org/10.5656/KSAE.2009.48.3.393]

- Lee, S. B., K. H. Park, Y. C. Choi, W. T. Kim, S. W. Kang, Y. B. Ihm, K. S. Han and I. G. Park. 2012. Comparison of the Pollinating Activities of Bombus terrestris Hive Produced by Domestic Bumblebee Rearing Companies at the Beefsteak-tomato Houses in Korea. J. Apic. 27(4): 275-282

- Likeda, F. and Y. Tadauchi. 1995. Application of bumblebee as pollinators on fruit vegetables. Honeybee Sci. 16: 49-53.

-

O’Donnell, S., M. Reichardt and R. Foster. 2000. Individual and colony factors in bumble bee division of labor (Bombus bifarius nearcticus Handl; Hymenoptera, Apidae). Insectes Soc. 47: 164-170.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00001696]

- Patiguli, S. Yang, B. Wang, G. R. Zhang, T. Yang and Q. H. Yu. 2010. Effects of seeding date of processing tomato in stubble-field on yield in South Xinjiang. Xinjiang Agric. Sci. 47: 1501-1506.

-

Plowright, R. C. and B. A. Pendrel. 1977. Larval growth in bumble bees (Hymenoptera-Apidae). Can. Entomol. 109: 967-973.

[https://doi.org/10.4039/Ent109967-7]

- R Core Team. 2021. R: a language and environment for statistical computing.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). 2009. Tomato culture (Standard textbook for farming) 393p. RDA Press, Suwon, Korea.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). 2017. Tomato. 371p. RDA Press, Jeonju, Korea.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). 2018. Tomato. pp. 47-49. RDA Press, Jeonju, Korea.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). 2020. Tomato. 357p. RDA Press, Jeonju, Korea.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA). 2023. Pollinating insects, bees. 139p. RDA Press, Jeonju, Korea.

- Seeley, T. D. and B. Heinrich. 1981. Regulation of temperature in nests of social insects. pp. 159-234. in Insect thermoregulation ed. by B. Heinrich. New York: J. Wiley.

-

Sutcliffe, G. H. and R. C. Plowright. 1990. The effects of pollen availability of development time in the bumble bee Bombus terricola K. (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Can. J. Zool. 68: 1120-1123.

[https://doi.org/10.1139/z90-166]

-

Velthuis, H. H. W. and A. van Doorn. 2006. A century of advances in bumblebee domestication and the economic and environmental aspects of its commercialization for pollination. Apidologie 37: 421-451.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2006019]

-

Vogt, F. D. 1986a. Thermoregulation in bumblebee colonies. I. Thermoregulatory versus brood-maintenance behaviours during acute changes in ambient temperatures. Physiol. Zool. 59: 55-59.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/physzool.59.1.30156090]

-

Vogt, F. D. 1986b. Thermoregulation in bumblebee colonies. II. Demographic variation throughout the colony cycle. Physiol. Zool. 59: 60-68.

[https://doi.org/10.1086/physzool.59.1.30156091]

-

Weidenmüller, A., C. Kleineidam and J. Tautz. 2002. Collective control of nest climate parameters in bumblebee colonies. Anim. Behav. 63: 1065-1071.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.3020]

- Yoon, H. J., K. Y. Lee, I. G. Park, M. A. Kim and Y. C. Choi. 2011. Current status of insect pollinators use in tomato crop in korea. J. Apic. 26: 341-353.

- Yoon, H. J., K. Y. Lee, S. B. Lee, I. G. Park, S. J. Jang, Y. C. Choi, Y. S. Choi and G. G Lee. 2008. Research on the current status of insect pollinator use in Korea. J. Apic. 23: 295-304.

- Yoon, H. J., S. E. Kim, S. B. Lee and H. S. Sim. 2004. Comparison of the Colony Development in the Bumblebees, Bombus ignitus and B. terrestris. Korean J. Appl. Entomol. 43: 117-121