배(Pyrus pyrifolia N.) 개화기의 기상조건에 따른 꿀벌(Apis mellifera L.)과 서양뒤영벌(Bombus terrestris L.)의 화분매개활동 특성

Abstract

We investigated pollination and foraging activities of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) and bumblebee (Bombus terrestris L.) during flowering season of the asian pear (Pyrus pyrifolia N.) under different weather conditions. There was no significant statistical difference about the pollination activities of two species. However, the pollination activities of bumblebee were more active than those of honeybee under low temperature and rainfall period. The activities of honeybee and bumblebee were more influenced by temperature than other factors (i.e. illumination and wind velocity). Honeybee was more sensitive to temperature and illumination than bumblebee. At low temperatures (<20°C ) on cloudy days (<30,000 lux) with a certain wind velocity (>4.0 m/s), the pollination activity of the honeybee was lower twice than that of bumblebee. Therefore, the results from this study suggest that there was different foraging activity properties between honeybee and bumblebee, and bumblebee was more effective for pear pollination than honeybee under low temperature and bad weather during pear blossoming season.

Keywords:

Pear, Pollination, Weather condition, Foraging activity서 론

전 세계 작물의 75%는 부분적으로 화분매개자(pollinator)에 의존하고 있으며, 연 2,350~5,700억 톤의 작물생산은 화분매개자와 직접적인 관련이 있다고 보고되었다(IPBES, 2016). 더욱이, 인간이 섭취하는 작물의 84%는 화분매개곤충에 의해 수정이 이루어진다(Richards, 1993; Williams, 1994). 지구온난화 등 최근의 인위적인 기후 변화는 화분매개곤충의 감소 및 식물과 화분매개곤충 간의 상호관계 등에 문제가 발생하는 하나의 원인으로 여겨지고 있다(Biesmeijer et al., 2006). 특히, 평균 기온이 상승하거나 하락함으로 인하여 작물의 꽃가루, 꽃꿀, 개화량의 변화나(Saavedra et al., 2003; Koti et al., 2005), 화분매개곤충의 화분매개 활동특성, 생활사 변화 등의 생태·생리적인 문제를 야기 할 수 있다(Bosch et al., 2000; Radmacher and Strohm, 2011). 이러한 문제는 식물 개화시기와 화분매개곤충의 방화활동 시기의 불일치(Wall et al., 2003)를 일으킬 수 있으며, 종국적으로는 화분매개곤충의 멸종이나 식물-곤충간 상호작용의 붕괴가 일어날 수 있을 것으로 보고되었다(Memmott et al., 2007; Scaven and Rafferty, 2013).

국내에도 기후변화에 의해 농작물의 재배환경, 과수의 개화기 및 재배적지의 변화 등이 확인되었고(Lee et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010), 특히, 3~4월에 개화하는 낙엽과수의 경우 겨울철의 기온상승으로 인해 개화기간이 앞당겨져, 결실 불량이 나타나고 있다고 보고되었다(Jang et al., 2002; Seo and Park, 2003). 따라서 기상조건에 따른 화분매개곤충의 방화활동에 대한 연구는 계획적인 농작물의 수정에 있어 매우 중요하다고 할 수 있다(Choi, 1987). 이에 북미와 유럽에서는 주요 화분매개곤충인 꿀벌, 뒤영벌 및 뿔가위벌류의 방화활동과 온도, 조도, 풍속 등의 기상조건과의 상관관계에 대한 연구가 진행되었다(Vicens and Bosch, 2000; Peat and Goulson, 2005; Zisovich et al., 2012). 국내에서는 배 개화기에 기상조건에 따른 꿀벌의 방화활동 특성과(Choi, 1987; Choi and Kim, 1988), 사과 개화기에 기상조건에 따른 서양뒤영벌과 머리뿔가위벌의 활동특성에 대한 연구가 보고되었다(Yoon et al., 2013).

배(Pyrus pyrifolia var. culta Nakai)는 국내에서 사과와 더불어 가장 많이 재배되는 낙엽과수 중 하나이다. 또한, 배는 대표적인 자가불화합성 작물로 결실을 위해서 반드시 화분매개곤충을 통한 수분이나, 인공수분이 필요하다(Cho et al., 2007; RDA, 2013). 이에 배의 수분에 있어 화분매개곤충의 활동특성과 효율성에 대한 연구들이 진행되었다. Free(1993)와 Mayar and Lunden(1996)은 배에서 꿀벌과 뒤영벌의 화분매개 활동 특성을, Benedek and Ruff(1998)는 다양한 품종의 서양배(P. communis)에 대한 꿀벌의 화분매개특성을 비교하였다. 또한 배 품종별로 꿀벌의 방화활동 특성과 봉군의 효율적인 도입방법 둥이 보고되었다(Monzón et al., 2004; Stern et al., 2004). 국내에서는 배 개화기에 기상조건에 따른 꿀벌의 방화활동 특성분석과(Choi, 1987; Choi and Kim, 1988), 신고 배를 대상으로 한 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 및 인공수분의 수분효과 비교 등이 보고되었다(Lee et al., 2007).

배의 발아기와 개화기는 근 30년 동안 점차 빨라지는 경향을 보이고 있다(Yim et al., 2012). 따라서 개화시기에 이상저온이 나타난다면, 개화시기와 화분매개곤충의 활동시기가 달라져, 수분과 결실에 큰 손실을 입을 수 있다(Jang et al., 2002). 그럼에도 국내에서 배의 개화기에 기상에 따른 화분매개곤충의 활동특성에 대한 보고는 약 30년전의 데이터이거나, 기상요소별로 분석이 되지 않아 최근의 기상상황에 따른 적용이 어려움이 있다.

이에 본 연구는 배의 개화기의 기상상황에서 온도, 조도, 풍속 중 어떠한 요소가 화분매개곤충에 가장 큰 영향을 미치는지를 조사하였다. 아울러, 배 개화기에 저온, 우천 등 기상불량 시 적합한 화분매개곤충을 선발하기 위하여, 꿀벌과 뒤영벌의 활동특성을 확인하고, 기상조건에 따른 화분매개활동을 비교·분석하였다.

재료 및 방법

실험 곤충과 시험구 배치

배 개화기에 기상요소별 화분매개곤충의 활동 특성 비교실험은 전라남도 나주의 국립원예특작과학원 배 시험장 실험포장에서 2015년 4월 3일부터 4월 20일까지, 충청남도 아산시 둔포면 소재 농가포장에서 4월 10일부터 4월 22일까지 수행하였다. 실험곤충은 꿀벌(Apis mellifera L.)과 서양뒤영벌(Bombus terrestris L.)을 사용하였다. 각 조사지역별 배 꽃의 만개기는 Table 1에 표시하였다. 꿀벌은 양봉농가에서 구입한 이탈리안계 황색종을 사용하였고, 2014년 11월부터 4개월 월동 후 1개월 사양한 봉군을 사용하였다. 서양뒤영벌은 국립농업과학원 곤충산업과에서 2015년 2월부터 3개월간 26°C, RH 65%, 암조건에서 사육한 8세대 봉군을 사용하였다(Yoon et al., 2002). 실험대상 배는 아시아 배(Pyrus pyrifolia var. culta Nakai)로서 품종은 나주배 연구소의 경우, 망실에 11년생 ‘신고’, ‘만풍배’, ‘슈퍼골드’, ‘화산’품종을 노지에 11년생 ‘신고’, 황금배’, ‘추황배’, ‘화산’, ‘감천배’ 품종 등을 사용하였고, 아산 농가 포장의 경우, 8~15년생 ‘신고’, ‘화산’, ‘감천배’, ‘원황’ 품종을사용하였다.

실험장소는 망실과 노지로 나누어 배치하였다. 나주 배 연구소의 경우 망실은 540m2 면적을 2구역(꿀벌시험구, 서양뒤영벌 시험구)으로 나누어 각각 망실(mash: 2×2mm)로 밀폐하였고, 배 품종별로 8주씩 총 40주를 정식하였다. 꿀벌 시험구와 서양뒤영벌 시험구에는 각각 일벌 약 2,000마리와 100마리 봉군을 배치하였다. 노지는 3,000m2 면적 내 신고 80주 외에 품종별로 각각 20주씩 정식된 2개의 포장을 선정하였다. 각 포장에 꿀벌 시험구(일벌 약 10,000마리, 1봉군)와 서양뒤영벌 시험구(일벌 200마리, 5봉군)를 배치하였다. 각 시험구의 간섭을 줄이기 위하여 각 포장사이 거리는 1km 이상으로 정하였다(Table 2). 아산 농가포장의 경우 노지에서만 조사를 진행하였으며, 1ha 면적의 포장의 우측 끝에 꿀벌 시험구(일벌 약 10,000 마리, 1봉군)와 좌측 끝에 서양뒤영벌 시험구(일벌 200마리, 5봉군)를 배치하였다.

기상조건에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 화분매개활동 특성

배의 망실과 노지에서 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌을 대상으로 기상조건에 따른 화분매개활동을 조사하기 위하여 나주의 경우, 봉군 설치 후 7일(2015년 4월 10일), 8일(4월 11일), 10일(4월 13일)에, 아산의 경우 7일(4월 17일), 10일(4월 20일)에 오전 9시부터 19시까지, 2시간 간격으로 기상조건에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율을 조사하였다. 봉군의 설치는 일벌들의 시험구 내부 적응을 위하여 예상 개화기보다 3~4일 일찍 설치하였다. 아울러, 조사날짜 및 기간은 조생품종의 만개기와 수분수의 개화기를 고려하였고(Table 1), 배의 수정 적기가 개화 시작 3~4일이므로 이를 감안하여 설정하였다(RDA 2013). 조사시간은 이전 배에서 화분매개곤충의 활동 보고에 따라(Lee et al., 2007), 조도와 온도가 증가하기 시작하는 오전 9시 부터, 조도와 온도가 가장 낮아지는 시점인 19시 구간을 추가하여 조사시간을 설정하였다.

화분매개 활동비율은 5분간 봉군에서 출입하는 일벌의 수를 조사하여 총 출입봉의 수를 봉군의 총 일벌 수에 대한 비율로 나타내었다. 기상조건의 경우 2시간 마다 조도, 온도 및 풍속 등 3가지의 요인을 조사하였다. 온도는 Testo 176T4 temperature data logger(Testo, Germany)로 측정하였고, 결과는 10°C 이하, 10.1~15.0°C, 15.1~20.0°C, 20.1~25.0°C, 25.1~30.0°C로 나누어 분석하였다. 조도는 TM-204 Lux/Fc Lighter meter(Tenmars, Taiwan)로 측정하였고 0~20,000lux, 20,100~40,000lux, 40,100~60,000lux, 60,100~100,000lux로 나누어 분석하였다. 풍속은 Kestrel®2000 Pocket weather meter(Nielsen-Kellerman, USA)를 사용하여, 5분간 평균풍속 측정하였고, 측정된 데이터는 0.0~1.0m/s, 1.1~2.0m/s, 2.1~3.0m/s, 3.1~4.5m/s로 나눠 분석하였다. 각 구간은 통계분석을 위하여 임의로 온도는 5°C단위, 조도는 20,000lux 단위, 풍속은 1m/s 단위로 설정하였다. 그 외 강수량은 농업기상정보서비스(www.weather.rda.go.kr)에서 확인하였다. 아울러, 각 온도, 조도, 풍속 등 각각의 기상조건과 활동비율에 대하여 다중회귀분석의 표준화계수(Beta coefficient)를 계산하여, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동 및 기상조건의 관계를 확인하였다.

배 개화기에 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동 특성

배 개화기에 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동 특성을 확인하기 위하여, 앞선 같은 실험구에서 봉군 설치 후 7일, 8일, 10일, 총 3회에 걸쳐 오전 11시부터 17시 까지, 2시간 간격으로 30분간 망실과 노지실험구의 내의 화분수집봉 비율, 방화시간 및 꽃간이동시간 등을 조사하였다. 조사시간은 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌이 가장 활동이 활발한 시간으로 설정하였다. 화분수집봉 비율은 방화활동을 마치고 봉군으로 복귀하는 일벌 중 다리의 꽃가루솔에 화분단자를 달고 들어오는 일벌의 비율을 조사하였다. 방화시간은 일벌이 한 송이의 꽃에서 화밀 또는 화분을 수집하는 시간을, 꽃 간 이동시간은 한 꽃에서 다른 꽃으로 이동하는 시간을 측정하였다.

통계분석

개화기간 중 봉군방사 후 7, 8, 10일째 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동 비율 비교는 일원배치 분산분석(one-way ANOVA test)를 통하여 분석하였다. 기상조건에 따른 화분매개곤충의 활동변화를 확인하기 위하여 온도, 조도 및 풍속 각 요인에 따른 화분매개곤충의 화분매개 활동비율의 차이를 검정하였다. 다만 조도, 온도 및 풍속이 서로 연관이 되어있을 수 있으므로, 상관분석을 통하여 각 요인별로 상호간에 상관이 있는 요인은 찾은 후, 그 요인을 배제하여 공분산 분석(ANCOVA test)을 실시하였다. 또한 각 기상요인의 변화에 따른 화분매개 활동비율의 변화를 확인하기 위하여, 회귀분석(Regression analysis)을 통하여 회귀식을 산출하였다. 각 기상조건 범위 내에서 화분매개곤충들 간의 활동비율 차이는 T-test로 검정하였다. 곤충의 활동비율에 가장 큰 영향을 미치는 기상조건요인을 확인하기 위하여, 다중회귀분석(Multiple regression analysis)을 수행하였다. 화분매개곤충들 간의 방화활동 특성조사에서 시간대별 화분수집봉의 비율은 일원배치분산분석(one-way ANOVA test)을, 곤충 종류에 따른 화분수집봉 비율, 방화시간, 꽃간이동시간의 차이는 T-test와 welch’s T-test를 통하여 분석하였다. 분산분석을 통한 결과는 Tukey’s HSD test로 사후분석하였고, 모든 통계분석은 SPSS PASW 18.0 for windows 통계 패키지 프로그램(IBM, USA)을 사용하였다.

결과 및 고찰

기상조건에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 화분매개활동 특성

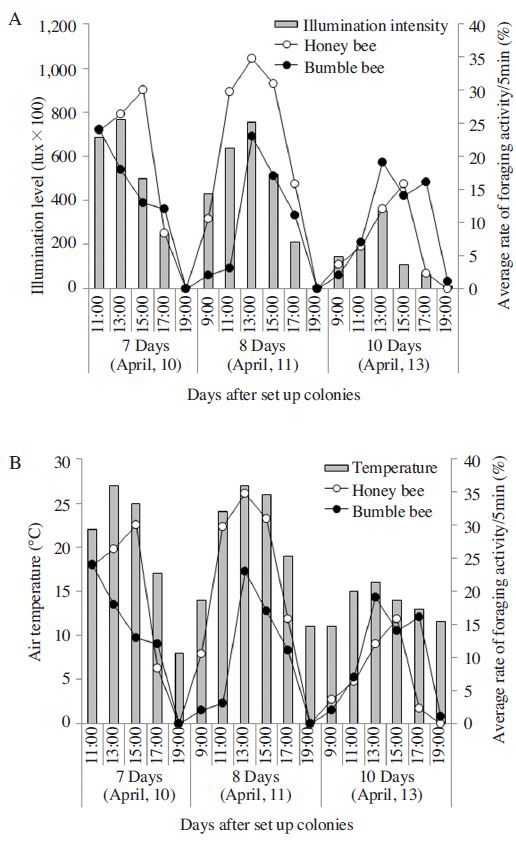

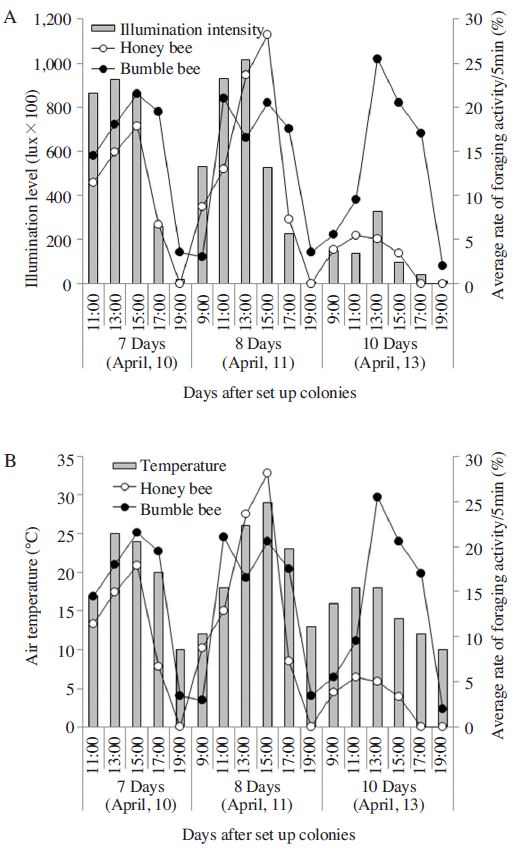

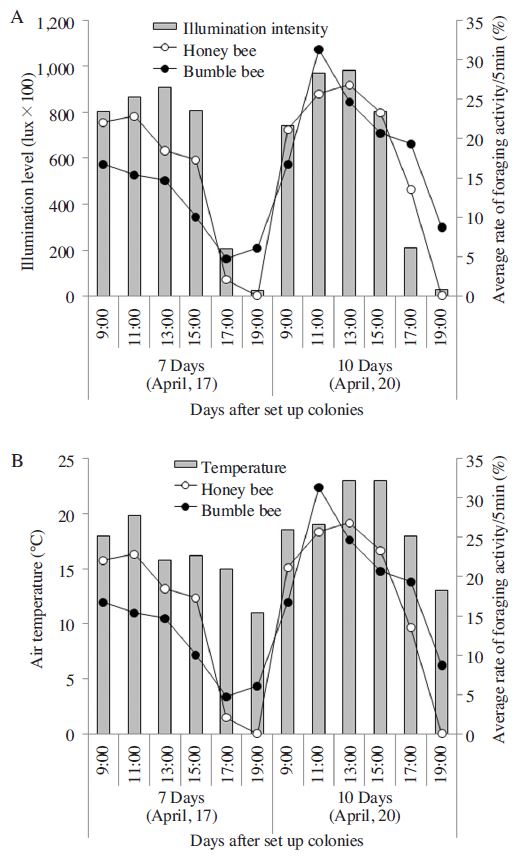

배의 조생품종 만개기를 중심으로, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동을 조사하였다. 전남나주배연구소에서 조사기간 동안의 기상환경은 봉군 설치 후 7일과 8일의 경우 09시부터 19시 동안, 최저온도 8~10°C, 최고온도 27~29°C, 최고조도 76,500~101,300 lux 그리고 강수량은 0.0mm로 맑은 날씨를 보여주었다. 그러나 10일차의 경우 최저온도 10~11°C, 최고온도 16~18°C, 최고조도 32,800~35,000lux, 그리고 강수량 7.5mm로 7일과 8일차와 비교하여 비교적 저온과 흐린 날씨 및 우천현상도 관측되었다(Fig. 1, 2). 충남 아산지역의 경우 봉군설치 7일차 최고온도 19.5°C, 최저온도 11°C, 최고조도 95,000lux이었고, 10일차 최고온도 23°C, 최저온도 13°C, 최고조도 98,400lux로 7일차는 10일차보다 기온이 평균 4°C 낮았으나, 조사기간 동안 맑은 날씨를 나타내었다(Fig. 3). 조사장소별로 망실 시험구는 노지 시험구보다 온도와 조도는 같거나, 약간 낮은 경향을 보여주었고, 풍속은 1/3 수준으로 낮았다(조도: T-test t(70)=-0.55, p=0.956; 온도: t(70)=-1.064, p=0.291; 풍속: t(70)=-5.223, p=0.0001).

The weather conditions including illumination (A) and temperature (B) and the rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in the pear orchard in 'Naju' during the experiment for net screen house. The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera differed significantly at day after set up colonies, in contrast foraging activity of B. terrestris did not differed significantly (one-way ANOVA test, A. mellifera: F(2,11)=4.999, p=0.029; B. terrestris: F(2,11)=0.742, p=0.498).

The weather conditions including illumination (A) and temperature (B) and the rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in the pear orchard in 'Naju' during the experiment for the open field. The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera differed significantly at day after set up colonies, in contrast foraging activity of B. terrestris did not differed significantly (one-way ANOVA test, A. mellifera: F(2,11)=5.363, p=0.024; B. terrestris: F(2,11)=0.231, p=0.797).

The weather conditions including (A) illumination and (B) temperature and the rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in the pear orchard in 'Asan' during the experiment for the open field.

설치날짜별 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율을 조사한 결과, 전반적으로 꿀벌은 설치날짜에 따라 활동비율에 유의미한 차이를 보였다. 망실에서 꿀벌의 경우 7일차 22.2±9.6%, 8일차 24.3±10.5%로 조도와 온도가 낮았던 10일차 8.0±5.8%보다 2.7~3배 유의미하게 높았다. 그러나 서양뒤영벌의 경우 같은 기간 11.6~16.7%의 활동비율로 통계적으로 비슷한 수준이었다. 노지 역시 망실과 같은 패턴을 보였는데, 꿀벌의 경우 7일차 12.7±4.8%, 8일차 16.1±9.3%로 10일차 3.5±2.2%보다 4.0~4.6배 높은 결과를 나타내었다. 서양뒤영벌의 경우 같은 기간 11.6~18.4%로 활동비율을 보여 설치날짜에 따른 유의미한 차이는 나타나지 않았다.

이러한 결과로 볼 때, 전반적으로 기상상황에 따라 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동차이가 있는 것으로 생각된다. Free(1993)와 Corbet(1993)은 서양뒤영벌이 15°C 미만의 저온이나 흐린 날에서 꿀벌에 비해 높은 활동성을 보고하였다(Free, 1993; Corbet, 1993).

망실에서 온도에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율을 조사한 결과, 꿀벌의 경우, 온도변화에 따라 통계적으로 유의미한 활동비율의 차이를 보였다. 20°C 초과에서 26.8~30.5%로 20°C 미만(10.1~20.0°C에서 9.5~10.6%)에 비해 2배 이상 높았으며, 특히 15°C 이하에서는 활동비율이 10%미만으로 떨어졌다(Table 3). 서양뒤영벌 역시, 온도변화에 따라 활동비율의 차이를 보여주었다. 그러나 꿀벌과는 달리 15°C 보다 높은 온도에서는 12.3~17.8%대의 고른 활동을 보여주었고, 10°C 이하에서 활동비율이 10%미만으로 떨어져 꿀벌에 비해 활동비율의 변화폭이 적었다(Table 3).

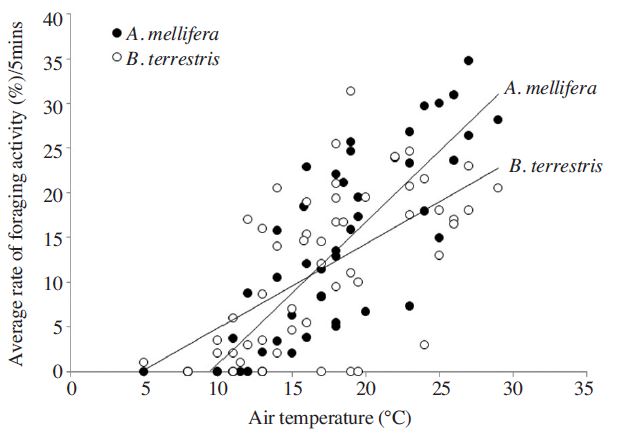

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris at different temperatures in pear orchard

노지에서 꿀벌의 경우, 통계적인 유의성은 없으나 온도변화에 따라 활동비율이 변화하는 경향을 보여주었다. 온도가 10~25°C 범위에서 3.0~10.6%였으나, 25°C 초과일 경우 22.2%로 2배 증가하였고, 20°C 이하부터 활동비율이 10% 미만으로 급격히 줄었다(Table 3). 서양뒤영벌의 경우, 온도의 변화에 따라 큰 폭의 활동비율 변화 없이 비슷한 수준의 활동비율을 보여주었다. 10~30°C 범위에서 11.0~18.3%의 활동비율을 보여주었고, 10°C 이하에서 활동비율이 10% 미만으로 떨어지는 경향을 나타내어, 꿀벌에 비해 온도에 따른 활동비율의 변화가 적었다. 망실과 노지에서 온도범위에 따른 활동량 패턴은 유사하였지만, 활동비율수치는 차이를 보였다. 이러한 차이는 망실용으로 쓰인 봉군의 크기가 다름으로 외역봉의 비율이 달라져 생기는 차이일 것으로 생각된다. 온도와 화분매개곤충의 활동에 대하여 회귀분석한 결과, 꿀벌은 서양뒤영벌에 비해 야외온도 변화에 민감하였다(Fig. 4). 온도범위에 따라서 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 간 방화활동 차이를 조사한 결과, 25°C 이상에서는 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌 보다 약 1.5배 높았다(T-test: t(12)=0.185, p=0.006). 20~24°C에서는 꿀벌, 서양뒤영벌 모두 같은 수준의 활동비율을 나타내었다. 15~19°C에서는 서양뒤영벌이 1.5배 높은 경향을 보였고(t(16)=-1.849, p=0.083), 15°C 이하에서는 통계적 유의성은 없으나, 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 1.9배 높은 활동비율을 보였다(t(12)=-1.361, p=0.198).

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in relation to air temperature. The regression equation for A. mellifera is y=1.583x-14.897 and the R2 value is 0.756 (ANOVA: F(1,50)=112.239, p=0.0001). The regression equation for B. terrestris is y=0.940x-4.463, and R2 value is 0.465 (ANOVA: F(1,50)=29.233, p=0.0001).

이상의 결과를 종합하여볼 때, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 모두 온도에 따라 화분매개 활동비율의 차이가 나타났고, 전반적으로 온도가 높아질수록 활동도 많아지는 경향을 보여주었다. 특히, 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌에 비해 온도변화에 민감하게 활동비율이 변화했다. 25°C 초과에서는 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌에 비해 1.5배 높은 활동비율을 보였지만, 15°C 이하의 비교적 저온에서는 오히려, 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율이 꿀벌의 약 2배 정도로 높았다. 뒤영벌은 꿀벌보다 온도에 대한 영향이 적거나(Wratt, 1968), 저온에서도 높은 활동성을 보이는데(Corbet et al., 1993), 이는 뒤영벌은 꿀벌이나 고독성 벌보다 더욱 효과적인 체내온도조절 기구를 가지므로, 낮은 주변 온도에도 활동의 제약이 적기 때문으로 보고되었다(Willmer, 1983; Stone and Willmer, 1989).

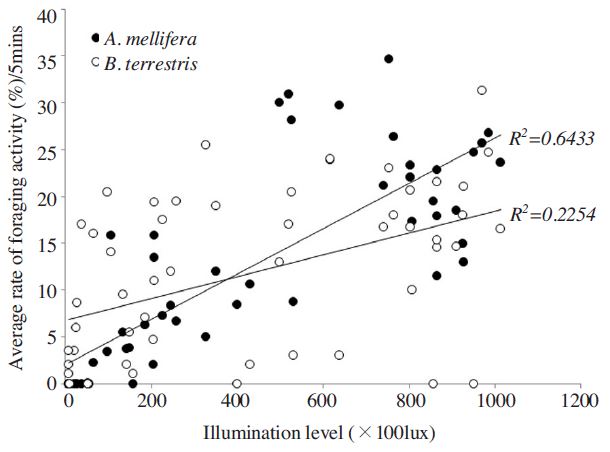

망실에서 조도에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율을 Table 4에 나타내었다. 망실 내에서 꿀벌의 경우 통계적인 유의성은 없었지만, 조도가 증가할수록 활동비율도 증가하는 경향을 보였다. 20,000lux부터 활동량이 증가하기 시작하여 100,000lux에는 20,000lux 대비 2배 이상 활동비율이 증가하였다. 서양뒤영벌의 경우 20,100~100,000lux범위에서 14.0~17.0%의 고른 활동비율을 나타내어 조도변화에 따른 통계적인 활동비율의 차이는 없었다.

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris at different level of illuminations in pear orchard

노지에서는 꿀벌의 경우 조도에 따른 방화활동이 통계적으로 유의미한 차이를 보였다. 조도에 증가에 따라 꿀벌의 활동비율도 증가하는 경향으로, 20,000lux부터 활동량이 증가하기 시작하여 100,000lux에는 20,000lux 대비 3배 활동비율이 증가하였다. 그러나 서양뒤영벌의 경우, 조도에 따른 활동비율의 유의미한 차이는 없었다. 조도와 화분매개곤충의 활동비율 간 회귀분석 한 결과(Fig. 5), 꿀벌은 조도에 대하여 상관관계가 있었고, 서양뒤영벌 경우, 조도와 낮은 상관관계가 있었다. 일부 관찰값 중 80,000~10,0000lux 사이의 활동비율이 50,000~ 80,000lux 사이의 활동비율보다 낮게 나타났는데, 이는 80,000~10,0000lux 당시의 온도가 20~21.5°C로 관측됨에 따라 25°C 이상이었던 50,000~80,000lux 범위에 비하여 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동이 떨어졌기 때문으로 판단된다. 조도범위 별로 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 간의 활동비율을 분석한 결과, 40,000lux 이상의 맑은 날은 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 약 1.4배 높은 활동비율을 보여주었다(T-test: t(126)=2.056, p=0.050). 그러나 40,000lux 이하 부터는 서양뒤영벌의 활동이 꿀벌보다 높은 경향을 보여주었는데, 20,000~39,000lux 범위에서는 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 약 1.9배 높은 활동비율을 보여주었고 통계적인 유의성이 인정되었다(t(10)=-3.017, p=0.013). 20,000lux 이하 범위에서는 서양뒤영벌과 꿀벌 모두 10% 미만의 활동비율을 보였으나 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율이 꿀벌보다 높은 경향이었다(t(30)=-1.926, p=0.064).

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in relation to the illumination level. The regression equation for A. mellifera is y=0.024x+2.015, and the R2 value is 0.643 (ANOVA: F(1,50)=90.182, p=0.0001). The regression equation of B. terrestris is y= -2.542x2+15.069x-6.414, and the R2 value is 0.494 (ANOVA: F(1,16)=7.326, p=0.006).

이상의 결과를 볼 때, 온도와 마찬가지로 꿀벌은 서양뒤영벌에 비해 조도변화에 더욱 민감했으며, 조도가 낮은 흐린 날씨의 경우 조도에 영향을 적게 받는 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 높은 활동비율을 보여주었다. Szabo(1980)은 3년간 꿀벌의 기상조건에 따른 활동을 조사한 결과, 꿀벌의 활동과 조도와 상관관계가 있음을 보고하였고, Vicens and Bosch(2000) 역시 사과에서 꿀벌 활동을 기상조건별로 분석한 결과, 조도에 영향을 받는 것으로 보고하였다. 꿀벌과 달리 뒤영벌의 활동은 토마토하우스 실험에서 상대습도나 조도와는 상관이 없는 것으로 보고되었다(Morandin et al., 2001). 벌목곤충은 가시광선 파장의 조도 외에 자외선 영역을 감지할 수 있고(Kevan et al., 2001), 뒤영벌 같은 벌목곤충은 자외선이 높게 투과되는 환경에서 더 높은 활동량을 보인다고 보고되었다(Costa et al., 2002). 따라서 차후 조도 외에 자외선 수치에 따른 화분매개곤충 간 활동특성의 차이도 조사되어야 할 것으로 생각된다.

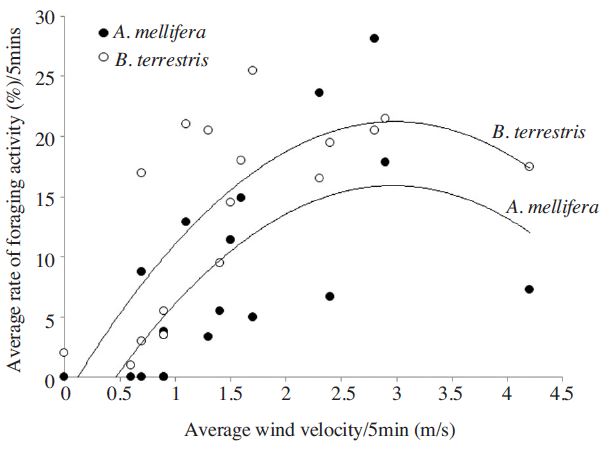

Table 5에는 5분간 평균풍속에 따른 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율을 나타내었다. 앞선 온도와 조도와는 달리 망실과 노지 시험구 모두 풍속에 따른 꿀벌의 활동비율의 차이는 없었으며, 서양뒤영벌 역시 유의미한 차이는 없었다.

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris at different wind velocities in a pear orchard

그러나 노지에서 풍속과 화분매개곤충의 활동비율에 대한 Dot plot 작성과 회귀분석을 한 결과, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율 모두 풍속의 특점시점까지는 정의상관을 보이다가 이후 감소하는 유의미한 이차회귀식의 형태를 확인할 수 있었다(Fig. 6). 꿀벌의 경우 전반적으로 평균 풍속 2.5m/s까지 활동이 늘어나다가 그 이후에는 급격히 감소하는 경향을 보였고, 서양뒤영벌의 경우는 3m/s까지 활동이 늘어나다가 3m/s 초과에서는 활동이 소폭 감소하는 경향을 보여주었다. 평균풍속 범위별로 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 간의 활동비율 차이를 분석한 결과, 바람이 불기 시작하는 1.0~2.0m/s의 범위에서 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율이 꿀벌보다 2.1배 높았고(T-test: t(10)=-3.091, p=0.011), 바람이 강한3.1~4.5m/s 범위에서는 2.7배 서양뒤영벌의 활동비율이 높았다(welch’s T-test: t(1.179)=-11.034, p=0.039). 바람이 거의 없는 0~1m/s의 범위와(T-test: t(12)=-1.357, p=0.200) 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동이 가장 많았던 2.1~3.0m/s 범위에서 활동비율의 차이는 나타나지 않았다(t(4)=-1.111, p=0.329). 전반적으로, 바람의 세기에 따라 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동이 변화하는 경향을 보였는데, 특정 풍속까지는 활동이 늘어났지만, 그 이상의 풍속에서는 감소하는 패턴이었다. 특히 서양뒤영벌의 경우, 3m/s 초과의 풍속에서 꿀벌보다 활동비율 높은 것으로 나타나 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 강풍 조건에 더 효율적일 것으로 생각된다. 일반적으로 꿀벌의 활동은 낮은온도와 높은 풍속에 저해받는 것으로 알려져있다(Abrol, 2015). Brittain(1933)은 사과 개화기에 3.1m/s의 풍속에서 꿀벌의 활동은 감소한다고 보고하여 이번 결과와 유사하였다. 뒤영벌의 경우, 꿀벌이 활동이 불가능한 6.7m/s에서도 활동이 가능하다고 보고된바 있고(Roubik, 1992), Yoon et al.(2013)은 4.1m/s의 풍속에서도 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동이 유지됨을 보고하였다. Broussard et al.(2011) 은 크랜베리의 개화기에 뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 높은 풍속에서 활동이 가능한 것으로 보고하였다.

The average rate of foraging activity of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in relation wind velocity measured at 5min intervals. The regression equation of A. mellifera is y= -2.542x2+15.069x-6.414 and R2 value is 0.494 (ANOVA: F(1,16)=7.326, p=0.006). The regression equation of B. terrestris is y=2.593x2+15.475x-1.798 and R2 value is 0.560 (ANOVA: F(1,16)=9.539, p=0.002).

온도, 조도, 풍속 중 어떤 요소가 가장 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동에 더 큰 영향을 미치는 지 확인하기 위하여, 다중회귀분석을 한 결과를 Table 6에 나타내었다. 꿀벌의 경우는 온도(ß=0.585)와 조도(ß=0.434)가 활동비율에 영향을 미치고, 온도가 조도보다 상대적으로 더 많은 영향을 끼쳤다. 서양뒤영벌은 온도(ß=0.698)만이 활동비율에 영향을 미쳤다. 풍속의 경우 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 활동에 영향을 미치지 못했다. 따라서 개화기의 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 활동에 실질적으로 가장 큰 영향을 끼치는 기상조건은 온도로 확인되었다. 또한, 서양뒤영벌은 꿀벌에 비해 온도에 영향을 적게 받는 것으로 판단된다(꿀벌 Adj. R2=0.721, 서양뒤영벌 Adj. R2=0.455). 이전 연구에서 배 개화기 때 꿀벌의 활동에 영향을 미치는 기상요인에 대한 결과는 보고자들 마다 달랐다. Choi(1987)와 Choi and Kim(1988)은 배 개화기 때 꿀벌활동과 일사량과 높은 상관관계가 있음을 보고하였고, Kim et al.(2002)은 온도만이 상관을 보인다고 보고하였다. 이러한 차이는 조사 시간이 오전부터 해가 지는 시각까지 조사가 되지 않았거나(Kim, 2002), 야외조사임에도, 조도와 온도의 상관관계를 고려하지 않은 분석을 했기 때문으로 생각된다(Choi, 1987).

배 개화기에 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동 특성

시간대별 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 5분간 화분수집봉의 비율을 조사한 결과를 Table 7에 나타내었다. 서양뒤영벌의 평균 화분수집봉 비율은 69.6±27.7%이었고, 꿀벌의 화분수집봉 비율은 31.2±13.7%이었다. 서양뒤영벌과 꿀벌의 화분수집 활동과는 뚜렷한 차이를 보였다. 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 모두 시간대별 화분수집봉의 비율은 통계적인 차이는 나타나지 않았다. Lee et al.(2007)은 망실 내에 배나무 개화기에 화분매개곤충을 방사하였을 경우, 꿀벌은 34.7%, 서양뒤영벌은 100%의 화분수집봉 비율을 보고하였다. 또한, 서양배 품종중 하나인 ‘Conference’에서 뒤영벌과 꿀벌의 화분매개활동을 조사한 보고에서는 뒤영벌의 꽃가루 수집량이 꿀벌보다 통계적으로 유의미하게 많음이 보고되었다(Jacquemart et al., 2006). 이렇게 뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 화분수집봉의 비율이 높은 이유는 뒤영벌의 경우 화밀을 2~4일 분만 저장하고, 이 후에는 유충에게 필요한 화분을 집중적으로 채취하기 때문으로 생각된다(Heirich, 1979). 또한, Lee et al.(2007)은 뒤영벌의 봉군 하부에 있는 먹이용 설탕물이 일벌과 유충의 먹이양에 충분하므로, 단백질원인 화분을 수집하는 일벌이 화밀을 수집하는 일벌보다 더 많다고 보고하였다. 그 외에도 꿀벌의 경우, 연구마다 다른 화분수집봉 비율을 보이는데, 1986년 다양한 품종의 배꽃에서 꿀벌의 화분수집봉에 대한 비율을 조사한 결과 36.1%로서 이번 조사결과와 유사하였지만(Choi and Kim, 1988), Benedek and Ruff(1998)은 13개의 품종의 배에서 방화활동을 한 꿀벌의 95.6%가 화분만을수집한일벌이었다고보고하였고, ’Comice’품종 배에서는 51.8%만이 화분수집봉으로 확인되었다(Monzón et al., 2004). 이는 꿀벌이 특정 꽃의 화분 또는 화밀을 수집하는 선호성이나, 수집능력이 유전적인 차이에 따라 달라질 수 있기 때문으로 생각된다(Graham, 1993; Rashad, 1957). Konzmann and Lunau(2014)는 뒤영벌 역시 일벌이 화밀을 수집하는 행동이나 화분을 수집하는 행동이 화밀의 성분이나 화분의 단백질 함량에 따라 변할 수 있음을 보고하였다.

화분매개곤충의 꽃 당 머무는 시간과 꽃 간 이동시간을 조사한 결과를 Table 8에 나타내었다. 꿀벌의 경우 꽃에 머무는 시간은 5.7±4.9초, 서양뒤영벌은 2.4±1.9초로 약 2.4배 정도 꽃에 머무르는 시간이 길었고 통계적인 유의성이 인정되었다. 꽃 간 이동시간은 통계적인 유의성은 없었으나, 꿀벌이 2.1±1.0초, 서양뒤영벌이 1.7±0.8초로 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 1.2배 더 긴 경향을 보였다. 따라서 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 꽃에서 화분매개하는 시간이 더 짧고, 다음 꽃으로 이동하는 시간 역시 더 짧은 경향을 보여 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 같은 시간에 더 많은 꽃을 방문하는 것으로 조사되었다. Free(1968)와 Kevan and Baker(1983)는 꽃의 화기구조에 따라 곤충간의 꽃을 방문하는 시간이나 횟수는 달라질 수 있지만, 일반적으로 같은 시간에 뒤영벌은 꿀벌보다 2배 이상 꽃을 방문한다고 보고하였다. 특히 라벤더 같은 화관통부(corolla-tube)를 가지는 꽃에서는 꿀벌보다 긴 혀를 가진 뒤영벌이 더 많은 화분매개활동을 한다고 보고하였다(Balfour et al., 2013). 그러나 사회성 곤충인 벌의 화밀 및 화분수집행동은 봉군의 내적환경요인, 벌의 환경적응, 기상조건 및 밀원식물의 형태 등에 의하여 차이를 보일 수 있다(Free, 1968; Menzel, 1979; Kevan and Baker, 1983). 예를 들면 시설 참외, 매실, 복분자 및 딸기에서는 서양뒤영벌의 꽃 체류시간이 꿀벌보다 짧았으나(Lee et al., 2010; Park et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2013), 고추, 파프리카, 참다래 및 시설 딸기 등에서는 오히려 꿀벌의 체류시간이 서양뒤영벌 보다 더 짧았다(Kim et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2008). 같은 ‘신고’ 품종의 배꽃에서도 본 연구는 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 3.3초 꽃에 더 오래 머문데 비하여, Lee et al.(2007)은 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 1.2초 정도 더 머무는 것으로 보고하였다. 특히 꿀벌의 경우는 배 꽃에 머무르는 시간이 보고자마다 차이가 큰데, Kim et al.(2002)은 약 5초라고 보고했고, Lee et al.(2007)은 3.5초로 보고하여 이번 연구결과와 차이가 있었다. Kim et al.(2003)은 외역봉들이 꽃에 머무는 시간이 봉군설치 날짜가 지날수록 통계적으로 유의미하게 떨어지고, 방화활동하는 벌이 화분수집봉(pollen-collector)인지 화밀수집봉(nectar-collector)인지에 따라 방화시간에서 차이 날 수 있음을 보고하였다. 따라서 이러한 차이를 설명하기 위해서는, 긴 시간동안의 관측을 통한 화분매개곤충별 방화시간 변화나, 방화하고 있는 곤충이 화분수집봉 인지, 화밀수집봉인지 구분하여 비교 조사하는 것, 그리고 꽃의 화기구조, 화밀, 화분의 양 등과 같은 꽃의 특성과 함께 조사하여 분석이 필요할 것으로 판단된다.

The visiting time on the flower and spending time from a flower to another flower of A. mellifera and B. terrestris in pear orchard

이상의 결과를 종합하여 볼 때, 배 개화기에 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 방화활동 특성이 차이가 있음을 확인할 수 있었다. 전반적으로 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 모두 기상조건 중 온도에 영향을 받는 것으로 나타났지만, 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 온도와 조도에 더 많은 영향을 받는 것으로 확인되었다. 특히, 20°C 이상의 온도, 40,000lux 이상의 조도, 평균 2m/s 이하의 풍속에서는 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 1.5~2.0배 높은 활동비율을 보여주지만, 20°C 이하의 온도, 30,000lux 이하의 흐린 날씨, 평균 풍속 4m/s 이상의 비교적 강풍 조건에서는 오히려 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌에 비해 높은 약 2배 이상의 높은 활동비율을 보여주었다. 배의 개화기는 주로 4월 초순에서 중순으로 이어지며 이때의 기상조건은 저온 또는 강우가 빈번하게 나타난다(KMA, 2010). 따라서 배의 개화기중 기상불량이나 저온이 지속될 경우 꿀벌보다는 서양뒤영벌을 화분매개용 곤충으로 이용하는 것이 효율적이라고 생각된다.

적 요

배 과수원에서 개화기의 기상조건에 따른 망실과 노지에서 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 화분매개활동 특성을 비교 조사하였다. 그 결과, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동은 통계적으로 유의미한 차이는 없었지만, 저온과 강우가 있는 날에는 서양뒤영벌이 꿀벌보다 유의미하게 높은 활동을 보였다. 온도, 조도 및 풍속별로 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌의 활동을 비교한 결과, 꿀벌과 서양뒤영벌 모두 조도와 온도변화에 영향을 받는 것으로 나타났고, 가장 높은 영향을 끼치는 기상요소는 온도였다. 꿀벌이 서양뒤영벌보다 온도, 조도에 더 민감한 활동변화를 보여주었다. 특히 20°C 이하, 30,000lux이하의 흐린 날씨 및 4m/s 이상의 바람이 부는 조건에서는 서양뒤영벌에 비해 꿀벌의 활동이 약 2배 이상 감소하였다. 따라서 배의 개화기중 기상불량이나 저온이 지속될 경우 꿀벌보다는 서양뒤영벌을 화분매개용 곤충으로 이용하는 것이 효율적이라고 생각된다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 국립농업과학원 농업기초기반 연구개발사업(과제번호: PJ01001003)의 지원에 의해 이루어진 것입니다.

인 용 문 헌

- Abrol, D. P., (2015), Pollination biology (Vol. 1). Pests and pollinators of fruit crops, Springer, Cham, Switzerland.

-

Balfour, N. J., M. Garbuzov, and F. L. Ratnieks, (2013), Longer tongues and swifter handling: why do more bumble bees (Bombus spp.) than honey bees (Apis mellifera) forage on lavender (Lavandula spp.)?, Ecol. Entomol., 38, p323-329.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/een.12019]

- Benedek, P., and J. Ruff, (1998), Flower constancy of honeybee and its importance during pear pollination, Acta Hort., 475, p427.

-

Biesmeijer, J. C., S. P. M. Roberts, M. Reemer, R. Ohlem?ller, M. Edwards, and T. Peters, (2006), Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands, Science, 313, p351-354.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127863]

-

Bosch, J., W. P. Kemp, and S. S. Peterson, (2000), Management of Osmia lignaria (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) populations for almond pollination: methods to advance bee emergence, Environ. Entomol., 29, p874-883.

[https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-29.5.874]

- Brittain, W. H., (1933), Apple pollination studies in the Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, Can. Dept. Agric. Bull., (n.s.), 162p1-198.

- Broussard, M., S. Rao, W. P. Stephen, and L. White, (2011), Native bees, honeybees, and pollination in Oregon cranberries, Hort. Sci., 46, p885-888.

- Cho, K. S., S. S. Kang, D. S. Son, S. B. Jeong, J. H. Song, Y. K Kim, M. S. Kim, K. H. Hong, H. M. Cho, and G. C. Koh, (2007), ‘Jinhwang’, a New mid-season pear with high quality and good appearance, Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol., 25, p133-137.

- Choi, S. Y., (1987), Diurnal foraging activity of honey bees in the pear blossoms, Korean J. Apiculture, 2, p108-116.

- Choi, S. Y., and Y.S. Kim, (1988), Diurnal foraging activity of honey bees in the pear blossoms (Ⅱ), Korean J. Apiculture, 3, p90-97.

- Corbet, S. A., (1993), Wild bees for pollination in the agricultural landscape, In: Bees for Pollination, Bruneau, E. Ed., p175-189, Commission of the European Communities, Brussels, Belgium.

-

Corbet, S. A., M. Fussell, R. Ake, A. Fraser, C. Gunson, A. Savage, and K. Smith, (1993), Temperature and the pollinating activity of social bees, Ecol. Entomol., 18, p17-30.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1993.tb01075.x]

-

Costa, H. S., K. L. Robb, and C. A. Wilen, (2002), Field trials measuring the effects of ultraviolet-absorbing greenhouse plastic films on insect populations, J. Econ. Entomol., 95, p113-120.

[https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-95.1.113]

-

Free, J. B., (1968), The Foraging behaviour of honeybees (Apis mellifera) and bumblebees (Bombus Spp.) on blackcurrant (Ribes nigrum), raspberry (Rubus idaeus) and strawberry (Fragaria×Ananassa) flowers, J. Appl. Ecol., 5, p157-168.

[https://doi.org/10.2307/2401280]

- Free, J. B., (1993), Insect pollination of crops, 2nd ed., Academic Press, London.

- Graham, J. M., (1993), The hive and the honeybee, Hamilton, Dadant and Sons, Illinois, USA.

- Heinrich, B., (1979), Bumblebee economics, p245, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (IPBES), (2016), Summary for policy makers of the assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services on pollinators, pollination and food production, IPBES, (deliverable 3 (a)) of the 2014-2018 work programme.

-

Jacquemart, A. L., A. Michotte-Van der Aa, and O. Raspé, (2006), Compatibility and pollinator efficiency tests on Pyrus communis L. cv. ‘Conference’, J. Hort. Sci. Biotech., 81, p827-830.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2006.11512145]

- Jang, H. I., H. H. Seo, and S.J. Park, (2002), Strategy for fruit cultivation research under the changing climate, Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol, 20, p270-275.

-

Kevan, P. G., and H. G. Baker, (1983), Insects as flower visitors and pollinators, Annu. Rev. Entomol., 28, p407-453.

[https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.28.010183.002203]

- Kevan, P. G., L. Chittka, and A. G. Dyer, (2001), Limits to the salience of ultraviolet: lessons from the birds and the bees, J. Exp. Biol., 204, p2571-2580.

- Kim, M. A., H. J. Yoon, I. G. Park, K. Y. Lee, and Y. M. Kim, (2013), Effect of insect pollinators for Korean raspberry (Rubus coreanus MIQ.) in the green house, Korean J. of Apiculture, 28, p323-330.

- Kim, S. Y., I. H. Heo, and S. H. Lee, (2010), Impacts of temperature rising on changing of cultivation area of apple in Korea, J. Korean Assoc. Reg. Geogra., 16, p201-215.

- Kim, Y. S., M. Y. Lee, and M. L. Lee, (2002), The pollination effect of honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) on pear blossom, Korean J. Apiculture, 17, p91-96.

- Kim, Y. S., J. W. Cho, M. Y. Lee, and M. L. Lee, (2003), The pollination of honeybee on peach blossom planted in vinyl house and its valuation of the fruits after harvest, Korean J. Apiculture, 18, p23-28.

- Kim, Y. S., S. B. Lee, H. S. Shim, M. L. Lee, M. Y. Lee, H. J. Yoon, S. H. Nam, and S. J. Chang, (2004), Pollination effect of honeybee (Apis mellifera) and bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) on hot and sweet pepper raised in vinyl house, Korean J. Apiculture, 19, p23-26.

- Kim, Y. S., S. B. Lee, Y. S. Jo, M. L. Lee, H. J. Yoon, M. Y. Lee, and S. H. Nam, (2005), The comparison of pollinating effects between honeybees (Apis mellifera) and Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) on the kiwifruit raised in greenhouse, Korean J. of Apiculture, 20, p47-52.

-

Konzmann, S., and K. Lunau, (2014), Divergent rules for pollen and nectar foraging bumblebees-a laboratory study with artificial flowers offering diluted nectar substitute and pollen surrogate, PLoS one, 9, pe91900.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0091900]

- Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA), (2010), A special report of abnormal climate in 2010, p31-33, KMA Press, Seoul, Korea.

-

Koti, S., K. R. Reddy, V. R. Reddy, V. G. Kakani, and D. Zhao, (2005), Interactive effects of carbon dioxide, temperature, and ultraviolet-B radiation on soybean (Glycine max L.) flower and pollen morphology, pollen production, germination, and tube lengths, J. Exp. Botany., 56, p725-736.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/eri044]

- Lee, D. B., K. M. Shim, and K. A. Rho, (2009), Strategy on adapting crop production to climate change, Korean J. Soil Sci. Fert., 42, p29-32.

- Lee, S. B., D. K. Seo, Y. S. Kim, N. I. Gwak, H. J. Yoon, H. C. Park, and S. J. Hwang, (2007), The pear flower-visiting insects, and the characteristics on pollinating activity of honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) and bumblebee (Bombus terrestris L.) at pear orchard, Korean J. Apiculture, 22, p125-132.

- Lee, S. B., N. G. Ha, K. Y. Lee, H. J. Yoon, I. G. Park, H. S. Gang, S. J. Hwang, M. Y. Lee, and K. Choi, (2008), Characteristics and effects on the pollinating activities of honeybee, Apis mellifera L. and white-tailed bumblebee, Bombus terrestris L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in strawberry vinyl houses, Korean J. of Apiculture, 23, p73-81.

- Lee, S. B., H. S. Sim, W. T. Kim, K. H. Park, S. J. Hwang, and Y. C. Choi, (2010), Characteristics of pollinating activities by Bombus terrestris worker, drone and Apis mellifera worker at the oriental melon houses, Korean J. of Apiculture, 25, p245-252.

- Lee, S., I. Heo, K. Lee, S. Kim, Y. Lee, and W. T. Kwon, (2008), Impacts of climate change on phenology and growth of crops: in the case of Naju, J. Korean Geogr. Soc., 43, p20-35.

- Mayer, D. F., and J. D. Lunden, (1996), A comparison of commercially managed bumblebees and honey bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) for pollination of pears, In VII International Symposium on Pollination, 437, p283-288.

-

Memmott, J., P. G. Craze, N. W. Waser, and M. V. Price, (2007), Global warming and the disruption of plant-pollinator interactions, Ecol. Lett., 10, p710-717.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01061.x]

- Menzel, R., (1979), Spectral sensitivity and colour vision in invertebrates, In: Handbook of Sensory Physiology, vol. VII/6A: Vision in Invertebrates, Ed. by H. Autrum, p503-580, Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

-

Monzón, V., J. Bosch, and J. Retana, (2004), Foraging behavior and pollinating effectiveness of Osmia cornuta (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on "Comice" pear, Apidologie, 35, p575-585.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2004055]

-

Morandin, L. A., T. M. Laverty, and P. G. Kevan, (2001), Effect of bumble bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae) pollination intensity on the quality of greenhouse tomatoes, J. Econ. Entomol., 94, p172-179.

[https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-0493-94.1.172]

- Park, I. G., H. J. Yoon, M. A. Kim, K. Y. Lee, S. B. Lee, and S. J. Jang, (2013), Effect on pollinating activities of honeybee (Apis mellifera), bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) and mason Bee (Osmia cornifrons) in japanese apricot field, Korean J. Apiculture, 28, p303-311.

-

Peat, J., and D. Goulson, (2005), Effects of experience and weather on foraging rate and pollen versus nectar collection in the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol., 58, p152-156.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-005-0916-8]

-

Radmacher, S, and E. Strohm, (2011), Effects of constant and fluctuating temperatures on the the development of the solitary bee Osmia bicornis (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae), Apidologie, 42, p711-720.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-011-0078-9]

- Rashad, S. E., (1957), Some factors affecting pollen collecting by honeybee and pollen as limiting factor in brood rearing and honey production, Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State College, USA.

-

Richards, K. W., (1993), Non-Apis bees as crop pollinators, Rev. Suisse Zool., 100, p807-822.

[https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.part.79885]

- Roubik, D. W., (1992), Ecology and natural history of tropical bees, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Rural Development Administration (RDA), (2013), Pear cultivation, p29, RDA Press, Suwon, Korea.

-

Saavedra, F., D. W. Inouye, M. V. Price, and J. Harte, (2003), Changes in flowering and abundance of Delphinium nuttallianum (Ranunculaceae) in response to a subalpine climate warming experiment, Glob. Change Biol., 9, p885-894.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00635.x]

-

Scaven, V. L., and N. E. Rafferty, (2013), Physiological effects of climate warming on flowering plants and insect pollinators and potential consequences for their interactions, Curr. Zool., 59, p418-426.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/czoolo/59.3.418]

- Seo, H. H., and H. S. Park, (2003), Fruit quality of ‘Tsugaru’ apples influenced by meteorological elements, Korean J. Agric. For. Meteor., 5, p218-225.

- SPSS PASW® Statistics 18.0, (2007), PASW® Core System User’s Guide, SPSS inc., USA.

-

Stern, R. A., M. Goldway, A. H. Zisovich, S. Shafir, and A. Dag, (2004), Sequential introduction of honeybee colonies increases cross-pollination, fruit-set and yield of ‘Spadona’pear (Pyrus communis L.), J. Hort. Sci. Biotech., 79, p652-658.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2004.11511821]

- Stone, G. N., and P. G. Willmer, (1989), Warm-up rates and body temperature in bees: the importance of body size, thermal regime and phylogeny, J. Exp. Biol., 147, p303-328.

-

Szabo, T. I., (1980), Effect of weather factors on honeybee flight activity and colony weight gain, J. Apic. Res., 19, p164-171.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1980.11100017]

-

Vicens, N., and J. Bosch, (2000), Weather-dependent pollinator activity in an apple orchard, with special reference to Osmia cornuta and Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae and Apidae), Environ. Entomol., 29, p413-420.

[https://doi.org/10.1603/0046-225X-29.3.413]

-

Wall, M. A., M. Timmerman-Erskine, and R. S. Boyd, (2003), Conservation impact of climatic variability on pollination of the Federally endangered plant, Clematis socialis (Ranunculaceae), Southeast. Nat., 2, p11-24.

[https://doi.org/10.1656/1528-7092(2003)002[0011:CIOCVO]2.0.CO;2]

- Williams, I. H., (1994), The dependence of crop production within the European Union on pollination by honey bees, Agric. Res. Rev., 6, p229-257.

-

Willmer, P. G., (1983), Thermal constraints on activity patterns in nectar-feeding insects, Ecol. Entomol., 8, p455-469.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1983.tb00524.x]

-

Wratt, E. C., (1968), The pollinating activities of bumble bees and honeybees in relation to temperature, competing forage plants, and competition from other foragers, J. Apic. Res, 7, p61-66.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1968.11100190]

- Yim, S. H., J. J. Choi, J. H Choi, J. H. Han, H. C. Lee, and S. G. Park, (2012), Injury of flower according to degree of low temperature in several asian pear cultivars, Korean J. Hortic. Sci. Technol, Abstracts, p102.

-

Yoon, H. J., S. E. Kim, and Y. S. Kim, (2002), Temperature and humidity favorable for colony development of the indoor-reared bumblebee, Bombus ignitus, Appl. Entomol. Zool., 37, p419-423.

[https://doi.org/10.1303/aez.2002.419]

- Yoon, H. J., K. Y. Lee, M. A. Kim, I. G. Park, and P. D. Kang, (2013), Characteristics on pollinating activity of Bombus terrestris and Osmia cornifrons under different weather conditions at apple orchard, Korean J. Apiculture, 28, p163-171.

-

Zisovich, A. H., M. Goldway, D. Schneider, S. Steinberg, E. Stern, and R. A. Stern, (2012), Adding bumblebees (Bombus terrestris L., Hymenoptera: Apidae) to pear orchards increases seed number per fruit, fruit set, fruit size and yield, J. Hort. Sci. Biotech, 87, p353-359.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.2012.11512876]