Opportunities and Constraints of Beekeeping Practices in Ethiopia

Abstract

Beekeeping has been practiced for centuries in Ethiopia. Currently, there are three broad classification of honey production systems in Ethiopia; these are traditional (forest and backyard), transitional (intermediate) and modern (frame beehive) systems. Ethiopian honey production is characterized by the widespread use of traditional technology resulting in relatively low honey yield and poor honey quality. Despite the challenges and constraints, Ethiopia has the largest bee population in Africa with over 10 million bee colonies, of which 5 to 7.5 million are hived while the remaining exists in the wild. Consequently, these figures, indeed, has put Ethiopia as the leading honey and beeswax producer in Africa. In fact, Ethiopia has even bigger potential than the current honey production due to the availability of plenty apicultural resources such as natural forests with adequate apiculture flora, water resources and a high number of existing bee colonies. However, lack of well-trained man powers, lack of standardization, problems associated with honey bee pests and diseases, high price and limited availability of modern beekeeping equipment’s for beekeepers and absconding and migration of bee colonies are some of the major constraints reported for beekeeping in Ethiopia. In this review, an attempt was made to present all beekeeping practices in Ethiopia. The opportunities and major constraints of the sector were also discussed.

Keywords:

Beekeeping, Beeswax, Honey, Practice, Challenges, Opportunity, EthiopiaINTRODUCTION

Ethiopia, with a total surface area of 1,127,127 km2, is located within the tropics in the Horn of Africa between 3° and 15°N latitude and 33° and 48°E longitudes (Fig. 1). According to the World Bank Report (2019), Ethiopia is the second most populous nation in Africa with about 105 million people in 2017, and the fastest growing economy in the region. However, it is also one of the poorest, with a per capita income of $783. Ethiopia aims to reach lower-middle-income status by 2025 (World Bank Report, 2019).

Geographic location of Ethiopia and major apicultural production regions. The major honey and beeswax producing regions are Oromia (41%), Amhara (22%), SNNPR (21%), and Tigray (5%).

Ethiopian is characterized by a wide range of agro-climatic conditions and biodiversity, which favor the existence of diversified honey bees and bee flora (Fichtl and Adi, 1994). When the Queen of Sheba went on her historic journey north to visit King Solomon, it was believed that she may have brought honey as a gift. At that time honey was considered as liquid gold. There are five subspecies of Apis mellifera distributed in Ethiopia (Mohammed, 2002). Due to a favorable climatic condition, Ethiopia has the largest bee population in Africa with over 10 million bee colonies, of which 5 to 7.5 million are hived while the remaining exist in the wild (Mo, 2007; Tadesse and Kebede, 2014). As a result, Ethiopia is the leading honey producer in Africa and one of the top ten countries (45,3000 metric tons) and fourth bee wax producer (3,800 metric tons) in the world (Fiku, 2015; Demisew, 2016).

According to a review report by Fikru (2015) that beekeeping has a substantial role in generating and diversifying the income of Ethiopian small landholder farmers and landless youths. In line with the government policy, the beekeeping sub-sector has a great opportunity to create job opportunity for smallholder in both rural and urban areas of the country (Assefa, 2011). A long lasting practice of beekeeping in Ethiopia has helped beekeepers develop indigenous knowledge on traditional hive manufacturing from different locally available materials. The main aim of this review was to share some experience of Ethiopia’s beekeeping practices to a wider world, including Koreans. Moreover, constraints and opportunities of beekeeping practices in the country were also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this review, an attempt was made to present and compile all beekeeping practices in Ethiopia, after consultation with experts in the area of apiculture in Ethiopia. Also, we have reviewed several research manuscripts published in the national and international journals, seminars, workshop proceedings, annual reports, and students’ dissertation. Honey bee diversity, honey production, opportunities and major constraints of the sector are also discussed. One of the authors (CJ) had a 4-day field trip to Jimma city of Oromia region of Ethiopia where the beekeeping is actively being practiced in the month of February. During the trip, some important information was gathered from public data and also by interviewing the government officers, union leaders, and beekeepers. A visit was also arranged to local market to have a quick look at the value-chain system of honey and other bee products.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Honey bee diversity

Ethiopia has a vast ecological diversity and a huge wealth of biological resources because of its geographical positions, range of altitudes, rainfall patterns and soil variability. This complex topography coupled with environmental heterogeneity offers suitable conditions for honey production. Ruttner (1976, 1988) assumed the bees of Ethiopia to be disjunctive populations of Apis mellifera monticola Smith, 1961, which was the subspecies of the mountains of Kenya and Tanzania. Afterward, the existence of three different subspecies in Ethiopia was suggested by Radloff and Hepburn (1997a); these were A.m. jemenitica Ruttner, 1976 in the North, A.m. scutellata Lepeletier, 1836 in the South, and A.m. bandasii Mogga, 1988 in the central mountains. Interestingly, five different subspecies were identified later in these regions (Amssalu et al., 2004). These identifications were all based on the morphological traits, such as wing and body characters, pigmentation and pilosity. It was interesting to note that Ethiopian honey bee populations seemed to be varied from the existing reference subspecies, after collecting mitochondrial DNA sequence information on the five subspecies (Franck et al., 2001).

Meixner et al. (2011) described the Ethiopian honeybee species as a single new subspecies, Apis melliferasimonensis, after analyzing some honeybee samples collected from 33 locations throughout Ethiopia. The name “simonensis” refers to the Semien mountains, which comprises the tallest peak (Ras Dejen) in Ethiopia. The body size of the worker bees of Apis mellifera simonensis is higher and larger than the East African mountain bee, A.m. monticola. Though, A.m. simonensis is only slightly smaller than the bees of Egypt, A.m. lamarckii, it is with much longer and broader wings. Compared with other honey bees of Africa, A.m. simonensis is very dark, although pigmentation can be variable. Selected morphometric characters of A.m. simensis were compared with surrounding African honey bee subspecies are discussed in Table 1.

Types of beekeeping practices in Ethiopia

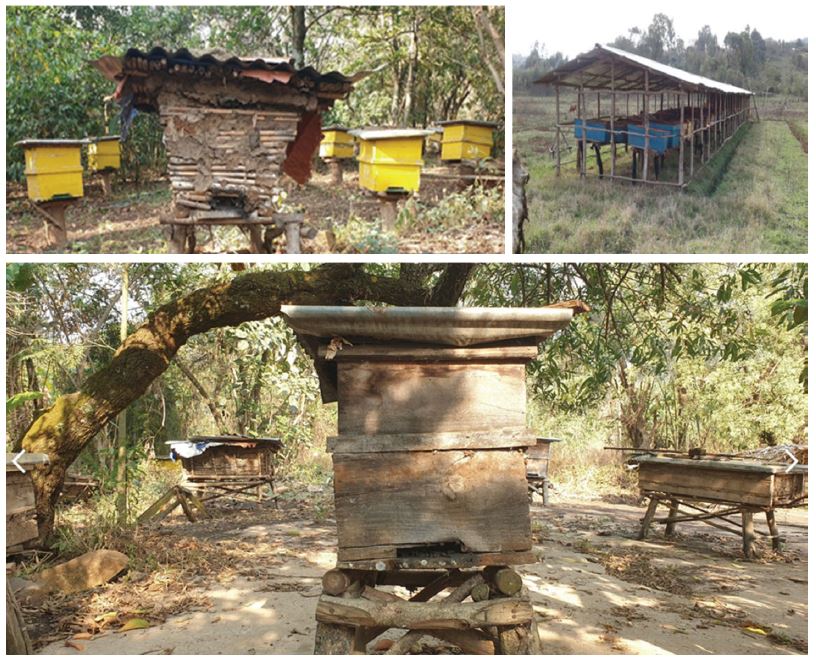

Currently, beekeeping practices in Ethiopia are broadly classified into three major groups, namely, traditional (forest and backyard), transitional (intermediate) and modern (frame beehive) systems (Teferi, 2018). These classifications are based on productivity and the technologies employed.

Traditional beekeeping

In Ethiopia, traditional beekeeping (Fig. 2) is the oldest practice, which has been carried out by the people for several years in almost all parts of the country (Fichtl and Adi, 1994; Sebsib and Yibrah, 2018). There are two traditional beekeeping types, namely forest and backyard beekeepings (Fig. 2). In some places, especially in the western and southern parts of the country, forest beekeeping is widely practiced by hanging a number of hives on trees. On the other hand, backyard beekeeping with relatively better management is common in most parts of the country (Birhan et al., 2015; Sebsib and Yibrah, 2018). Traditional beehives were categorized in to three different types; these include: Log (local name: Bidiru), Mud (local name: Dogogo) and Basket hive type, but all were oval in shape with the dimension of around 90 to 100 cm in length and a diameter of approximately 30 cm (Sebsib and Yibrah, 2018). According to the information gathered from beekeepers by Sebsib and Yibrah (2018) they were plastering interior of the hive by mud and cow dung to protect bees from cold weather conditions, and the exterior part were covered with grass and bamboo sheath (local name: hoyine) to protect from rain and sun. However, traditional beekeeping is often characterized by low honey yield and poor honey quality.

Traditional forest beekeeping: Traditional type of beekeeping practice (Fig. 2) includes the use of traditional techniques of harvesting honey and beeswax using various traditional styles (Belie, 2009; Fikru, 2015). Traditional forest beekeeping practice is putting of hives in the forest on very tall trees for catching swarms. This system is commonly practiced in the region where the forest coverage is high. Indeed, the forest-covered areas of the country is characterized by abundant water resources and high population of honeybees (Fikru, 2015). The advantage of forest beekeeping is that the honey bees do not sting and harm domestic animals and people. Moreover, the bees can get abundant forage plants in their vicinity. However, its disadvantages are lack of close follow up and also bad harvesting techniques employed by the local. During honey harvesting, beekeepers usually bring down the hive from the tree, and as a result, it damages the honeybee colony (Fikru, 2015). Honey harvesting activity of this practice was carried out at night using smokes. However, there is always a risk of falling down from the tree as the beekeeper climbs a tall tree in dark (Fikru, 2015).

Traditional backyard beekeeping: Backyard beekeeping (Fig. 2) is being undertaken in the vicinity of homestead areas to keep the honeybees safe. The advantages of such practices are: construction is very simple and does not require improved beekeeping equipment and skilled manpower. On the other hand, the disadvantages of this practice are an inconvenience to conduct internal inspection and feeding. In some places of the country the size of the hive is too small and causes swarming. According to the study reported by Tesfaye et al. (2017) the traditional backyard beekeeping with relatively better management than forest beekeeping was common in most parts of the country, particularly in Bale zone of south-eastern Ethiopia.

Transitional beekeeping

Transitional beekeeping practice (Fig. 3) was first introduced into Ethiopia in 1976. It is a type of beekeeping practice intermediate between traditional and modern beekeeping methods (Belie, 2009). It is one of the improved methods of beekeeping practices compared with those of traditional ones. There are three types of hives for this practice, namely Kenya Top Bar Hive (KTBH), Tanzania Top Bar Hive (TTBH) and mud-block hives. The KTBH has been proved to be the most suitable because of its low cost and its easiness of construction. Among these hives, KTBH is widely known and commonly used in many parts of the country (Belie, 2009).

The transitional hives can be constructed from timber, mud or locally available materials. Each hive carries 27-30 top bars on which honeybees attach their combs. The top bars have 3.2 cm and 48.3 cm in width and length, respectively. Transitional beekeeping practice has the following advantages (Fikru, 2015); easy access to hives to monitor, bees are guided into building parallel combs by following the line of the top bars, the top bars are easily removable and this enables beekeepers to work fast, the top bars are easier to construct than frames, honeycombs can be removed from the hive for harvesting without disturbing combs containing broods, and the hive can be suspended with wires or ropes and this gives protection against pests. On the other hand, this practice has its own disadvantages such as, top bar hives are relatively more expensive than traditional hives, combs suspended from the top bars are more apt to break off than combs which are building within frames (Fikru, 2015).

Modern beekeeping

Equipped with the right modern techniques, honey production in Ethiopia has the potential to pull thousands of poor farmers out of poverty. Modern beekeeping practices (Fig. 4) are required to provide the maximum honey yield for long time without harming bees (Nicola, 2002). Modern movable-frame hive consists of precisely made rectangular box hives superimposed one above the other in a tier (Belie, 2009). The number of boxes is varied according to the population size of bees and the season. In Ethiopia, about 5 types of movable frame hives were introduced since 1970. Zandar and Langstroth hives are the most commonly used in the country. Other modern hives such as Dadant, modified Zandar, and foam hive are found rarely (Belie, 2009; Fikru, 2015). Improved box hive has advantages over the traditional and transitional hives in that it gives high honey yield in quality and in quantity. The other advantages of the improved box hive are its possibilities of swarming control by spurring the bees from place to place for searching honeybee flower and pollination services. Based on the national estimate, the average yield of pure honey from movable frame hive is 15~20 kg/year, and the amount of beeswax produced is 1~2% of the honey yield (Gezahegne, 2001). However, in potential areas, up to 50~60 kg honey harvest has been reported (Belie, 2009). Movable frame hives allow colony management and use of a higher level of technology, with larger colonies, and can give higher yield and quality honey but are likely require high investment cost and trained manpower (Belie, 2009; Fikru, 2015).

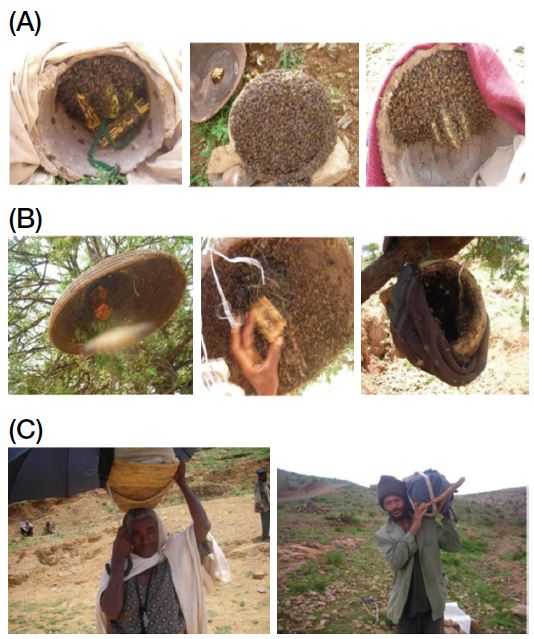

Honeybee colony transport and marketing

Marketing on honeybee colony (Fig. 5) is becoming a common practice in Bure district of Amhara region of Ethiopia, in which colonies are carried to market when a beekeeper household decides to sell a honeybee colony (Belie, 2009). Only a small portion of the respondents (14.4%) had the experience of selling honeybee colonies (Belie, 2009). The price of one bee colony ranged from 75.00 to 160.00 Ethiopian Birr (ETB) with an average of 117.50 ETB (Belie, 2009). According to the respondents, the selling price of one bee colony is drastically increasing from time to time. This fact may be attributed to decrease in the trend of honeybee colonies due to different reasons such as environmental degradation, intensification of agriculture, poisoning of honeybees and increased attention to the beekeeping sub-sector by the government by involving non-beekeepers through improved beekeeping practices (Belie, 2009).

Honey bee colony and queen market: (A) Varieties of colonies in the colony markets. Source: (Gebretinsae and Tesfay, 2014); (B) Worker bee attraction and queen selling: Source: (Gebretinsae and Tesfay, 2014); (C) Methods of colony transporting to and from market: Source: (Gebretinsae and Tesfay, 2014).

A related study conducted in Tigray region, north part of the country both honeybee colony sellers and purchasers transported their colonies to and from the markets by putting them in a woven basket (Gebretinsae and Tesfay, 2014). Traditional hives that contain colonies for sale are fixed on top of a forked wooden tool of greater than or equal to the length of the hive (Fig. 5). The wooden tool is needed to assist in holding the hive and minimizing its breakage. To avoid heat accumulation inside the hives and damage to the bees, sellers travel early in the morning and attentively monitor the sound of their bees. When the vibrating sound of bees is increased in an effort to maintain the temperature of the hive, colony sellers go to a shelter and let the colonies rest and cool down by opening their cover (Fig. 5). Additionally, the beekeepers smear their hives with aromatic plants and put their queens inside the hive then hang them on trees in the market (Fig. 5).

The number of colonies markets was the lowest in July and reached a peak in the 2nd and 3rd weeks of August in the Tigray region of Ethiopia (Gebretinsae and Tesfay, 2014). After young colonies with a new queen and not well-established colonies started to appear in the markets (Fig. 5). Gebretinsae and Tesfay (2014) reported that poor technical knowhow and lack of regulation are among some of the major problems in honeybee marketing. For instance, deserting worker bees are marketed as if a colony. Other common problems are marketing queenless colonies, and selling unfertilized queens. Therefore, honeybee colony transportation and marketing is one important issue that the government needs to intervene to have a smooth and fair marketing.

Honeybee pests and predators

There were several studies conducted in different regions of Ethiopia to know the extent of problems associated with pests and diseases. As indicated in Table 2, the occurrence of pests was one of a major challenge to the honeybees and beekeepers. After having identified the major pests facing the beekeepers, they were requested to rank them. Interestingly, beekeepers identified ants as their first challenge, followed by wax moth, and bee lice. Small hive beetles, birds, spider, honey badger, termite, and snake were also problems of beekeeping and their priority depends on the regions (Table 2).

Constraints of beekeeping in the country

In order to utilize the beekeeping sub-sector, identifying the existing constraints and searching for solutions are very important. There were several studies conducted by interviewing beekeepers in different honey producing regions of Ethiopia (Belie, 2009; Ejigu et al., 2009; Yemane and Taye, 2013; Beyene and Verschuur, 2014; Gebretsadik and Negash, 2016; Tesfaye et al., 2017; Ambaw and Teklehaimanot, 2018) (Table 3). Participants of the study identified major constraints of beekeeping in the country. Based on those findings, beekeepers much suffered from a number of constraints and challenges that are antagonistic to in honey production. Some of the major problems in beekeeping are caused by bee characteristics or environmental factors that are beyond the control of the beekeepers which include too much application of pesticides and herbicides, lack of forages, honeybee pests and predators, lack of beekeeping equipment such as modern hives and its accessories (Table 3). Even beekeepers who are using the top bar and moveable frame type hives lack protective cloth, smoker, casting mold and honey extractors, without which improved beekeeping practices can’t be successful (Belie, 2009). Additionally, apiculture equipment is expensive relative to the purchasing power of the beekeepers and they have also a knowledge gap (Belie, 2009). Therefore, the adoption of improved beekeeping practices also relies on the supply of these basic inputs.

While others are due to problems connected with poor marketing infrastructure and storage facilities. Though Ethiopia is the leading country in honey production, not all productions are delivered for export. Honey is mainly used for local consumption purpose and to a very large extent (80%) for brewing of mead, locally called ‘Tej’ the national drink made from fermented honey (Hartmann, 2004).

In some regions forage is also the main constraint which is resulted from increasing deforestation and overgrazing and lack of attention to introduce potential bee forage plants. The disappearance of woody vegetation and overgrazing has nearly depleted the bee forage supply. The supply of natural bee forage is disappearing and as consequence bee colonies are suffering, ultimately resulting in low yield (Belie, 2009). Therefore, beekeepers have to provide supplementary feed to their colony, planting drought-resistant bee forage species around the apiary and provide water to the colony (Belie, 2009).

Opportunities of honey beekeeping in the country

According to CSA and Agricultural sample survey reported by Lewoyehu and Amare (2019), the major honey and beeswax producing regions in Ethiopia are Oromia (41%), Amhara (22%), SNNPR (21%), and Tigray (5%) (Fig. 1). In Ethiopia, beekeeping is an integral part of the lifestyle of the farming communities, except for a few areas. It is a common practice in every place where humankind has settled. In addition, Ethiopia has probably the longest tradition of all the African counties in beeswax and honey marketing. Fikru (2015) reviewed the time is immemorial as to when and where marketing of honey and beeswax has been started in the country. Beekeeping is a sub-sector which is important for the economic development of the country as results of its benefits to the environment, conservation of native habitats and its potential to increase the yield of food and forage crops. The direct contribution of beekeeping includes the value of the outputs produced such as honey, bee wax, queen and bee colonies, and other products such as pollen, royal jelly, bee venom, and propolis in cosmetics and medicine (Gezahegn, 2001). There is still huge potential to increase honey production and to improve the livelihood of the beekeepers in Ethiopia.

Plentiful forage availability coupled with favorable and diversified agro-climatic conditions of Ethiopia create conducive conditions for the growth of 6000~7000 species of flowering plants (Fichtl and Adi, 1994) which has supported the existence of large number of bee colonies in the country (Kinati et al., 2012; Shibru et al., 2016) (Table 4). It is estimated that over two million bee-colonies in the countries exist in the forest and crevices. The density of hives occupied by the honeybees on the land may be the highest compared with any country in the African continent (Fikru, 2015). Other opportunities include water availability, indigenous beekeepers knowledge, and experience, socioeconomic value, experience in beekeeping, market demand of bee products and establishment of Ethiopian beekeeping association and favorable government policy and NGOs involvement in the beekeeping activities (Kinati et al., 2012; Shibru et al., 2016).

NGOs are also giving more attention to the sub-sector than ever before as an important intervention to support the poor and particularly the women. These intervention by NGOs has provided the Ethiopian farmers the opportunity to access improved technologies and capacity building (training on apiculture). Moreover, the Ministry of Agriculture and the leading business associations such as beekeepers unions and cooperatives, the Ethiopia Beekeepers Association (EBA) and the Ethiopian Honey & Beeswax Producers and Exporters Association (EHBPEA) take high responsibility and did actively participate to enhance quality honey production (Belie, 2009). These institutions will give a good opportunity to create increasing demand for honey and competitive market in different regions and to promote export of hive products, which will, in turn, result in endogenous technological change and overall development in the sub-sector in the country. In addition to the existing natural base, the Ethiopian government has put in its agenda the need to develop apiculture as one of the strategies to reduce poverty and to diversify national exports (Belie, 2009; MoA and ILRI, 2013).

Potential of honey production in Oromia region

Oromia is one of the nine National regional states of Ethiopia (Fig. 1). The region covers 363,315 km2, accounting 34.3% of the total area of the country. Oromia region has a wide range of agro-ecological and climatic zones, natural and cultivated flora well suited to beekeeping. The climatic conditions prevailing in the region are grouped into 3 major categories: the dry climate, tropical rainy climate and temperate rainy climate. The altitude ranges from 500 masl to the highest peak, Mt. Batu (4607 masl). Jimma, Ilu Aba Bor, West Wollega, Kellam Wollega, Horo Guduru Wolega, Guji, and West Shoa are among high potential zones for beekeeping subsector in the region.

Oromia has high water resources which include major rivers such as Awash, Wabe-Shebele, and Genale, as well as lakes, such as Bishoftu, Kuriftu, and Bishoftu-Gudo. Oromia has a diversified honey flora, growing wide range of flowering field crops and vegetables and fruits The natural and cultivated flora well suited to beekeeping in the region includes Eucalyptus sp., Cordia africana, Acacia sp., Hygenia abyssinica, Croton macrostachus, Guizota scabra, Coffea arabica, Ricinus communis, Euphorbia sp., Erythrinia abyssinica, Syzygivm guinees, Callistemon citrunus, Schefflera abyssinica, and Anigaria altisma are some of the tree species sources of both pollen and nectar (Oromia Livestock & Fishery Resource Development Bureau). Oromia contributes 41~50% of the country’s honey and beeswax production, which is considered only as 10% of the potential in this region (Lewoyehu and Amare, 2019; Oromia Livestock & Fishery Resource Development Bureau). The high potential of bees’ product in the region is due to the availability of a large number of native bee colonies, variable climate, and honey bee floras which include natural trees, forage plants, horticultural and cultivated crops. The region has a large number of bee colonies accounting about 60% of bee colonies in the country. Over 6.3 million honey bee colonies are estimated to exist in the region (Oromia Livestock & Fishery Resource Development Bureau).

Quality of Ethiopian honey

Ethiopian honey production is characterized by the widespread use of traditional technology resulting in relatively low honey yield and poor quality. Despite the low yields, Ethiopia remains one of the world’s largest honey producers and a leader in Africa. There are some attempts to improve the quality of honey n Ethiopia. According to the reports by the African Business Magazine (2012) Ethiopian honey has began marketing honey as a high-quality and well-packaged product. CONAPI, Slow Food and other Italian NGOs have helped Ethiopian beekeepers improve the production process, packaging and label the product. Then so far, Slow Food has given its recognition of approval and guaranteeing the quality of seven different types of honey, under the honeys of Ethiopia label, namely the Tigray white honey, the Wenchi volcano honey, the Dawro Konta honey, the Wolisso honey, the Shalala honey, the Horde honey and the Getche honey (African Business Magazine, 2012). Ethiopian honey comes from different regions, each with a unique environment, climate and flora to make distinctive honey (Fig. 6).

Some typical Ethiopian honey samples: (A) Honey extraction by hand squeezing; (B) Dark brown honey from Vernonia spp. (particularly, Vernonia amygdalina, locally called Grawa) tree; (C) Red-brown honey from sunflower, black mustard and papaya and mango trees; (D) White honey from Becium grandiflorum (locally called Tebeb).

One of the major constraints of honey production in Ethiopia is the lack of standardization. Honey and its by-products are susceptible to adulteration. Some of the possible adulterants are corn syrup, sugar etc. Therefore, honey standards and certification are an important way for consumers to know the quality and the consistency of the product. Physicochemical (moisture, reducing sugar, sucrose, water-insoluble, ash, free acid, hydroxymethylfurfural contents, pH, electrical conductivity and specific rotation), sensorial and microbiological characteristics are used to determine the quality of honey. The physicochemical properties for given honey are influenced by the nectar types that the honey bee used, geographical ecology (climatic and soil) and postharvest honey handling practices. Evaluation of the physicochemical properties of honey harvested from traditional and frame hives located in the Harenna forest, Bale, Ethiopia showed all quality indicators of honey from traditional and frame hives were within the criteria set by Codex Alimentarius (CA), European Union (EU) and Ethiopian standard, except for water insoluble solids (Belay et al., 2013).

Future perspectives

Ethiopia has huge potential to increase honey productivity and its by-products due to the country’s favorable climatic conditions for beekeeping practice. Beekeeping practices are known as less labour intensive and environmentally friendly compared to other agricultural activities like livestock. Thus, beekeeping business activities have the potential to provide a wide range of economic benefits. There are two main economic benefits from engaging in beekeeping business: income generation by selling honey and its by-products (beeswax, royal jelly, pollen, propolis, bee colonies, and bee venom) and the creation of employment opportunities, especially for women and youth. Insects, particularly honey bees, are the major sources of crop pollination, accounting one-third of food crops. Thus, agricultural productivity and conservation of natural flora can be greatly benefited from beekeeping activities. Beekeeping can coexist almost effortlessly with regular farming activities due to its relatively low labor requirements, Thus, beekeeping business is a promising non-farm activity for the rural and urban households which can, directly and indirectly, contribute to the incomes of households and the economy of the country. The economic importance of bee products also includes foreign currency earning, employment opportunity, income generation, row materials and poverty alleviation., Therefore, an understanding of honey production in Ethiopia is very important for the development of the country in general and increases the cultural values, gender inclusive activities, the diet and the industry input.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported in part by the Basic Science Research Programme through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862).

References

- African Business Magazine, (2012), Honey: Ethiopia’s liquid gold, https://africanbusinessmagazine.com/uncategorised/honey-ethiopias-liquid-gold// Accessed on January 26, 2018.

- Ambaw, M., and T. Teklehaimanot, (2018), Characterization of beekeeping production and marketing system and major constraints in selected districts of Arsi and West Arsi zones of Oromia region in Ethiopia, Children, 6, p2408-2414.

-

Amssalu, B., A. Nuru, S. E. Radloff, and H. R. Hepburn, (2004), Multivariate morphometric analysis of honeybees (Apis mellifera) in the Ethiopian region, Apidologie, 35, p71-81.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2003066]

- Assefa, M., (2011), Pro-poor value chains to make market more inclusive for the rural poor: Lessons from the Ethiopian honey value chain, Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen, Denmark, p35-50.

- Ayalew, K., and T. Gezahegn, (1991), Suitability Classification in Agricultural Development, Ministry of Agriculture, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

-

Belay, A., W. Solomon, G. Bultossa, N. Adgaba, and S. Melaku, (2013), Physicochemical properties of the Harenna forest honey, Bale, Ethiopia, Food Chem., 141(4), p3386-3392.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.06.035]

- Belay, F., A. Daba, and W. Oljirra, (2016), The significance of honey production for livelihood In Ethiopia, J. Environ. Earth Sci., 6(4), ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online).

- Belie, T., (2009), Honeybee production and marketing systems, constraints and opportunities in Burie District of Amhara Region, Ethiopia, Bahir Dar University.

- Beyene, T., and M. Verschuur, (2014), Assessment of constraints and opportunities of honey production in Wonchi district South West Shewa Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia, Am. J. Res. Commun., 2(10), p342-353.

- Birhan, M., S. Selomon, and Z. Getiye, (2015), Assessment of challenges and opportunities of beekeeping in and around Gondar. University of Gondar, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ethiopia, Acad. J. Entomol., 8(3), p127-131.

- Daba, F. B., and O. W. Alemayehu, (2016), The Significance of honey production for livelihood in Ethiopia, Environ. Earth Sci., 6(4), ISSN 2224-3216 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0948 (Online).

- Demisew, W., (2016), Beekeeping in Ethiopia: country situation paper presented to 5th annually African Association of Apiculture Exporter, 21-26 September 2016, African Association of Apiculture Exporter, Kigali, Rwanda.

- Ejigu, K., T. Gebey, and T. Preston, (2009), Constraints and prospects for apiculture research and development in Amhara region, Ethiopia, Livestock Res. Rural. Dev., 21(10), p172.

- Fichtl, R., and A. Adi, (1994), Honeybee flora of Ethiopia, Margraf Verlag.

- Fikru, S., (2015), Review of honey bee and honey production in Ethiopia, J. Anim. Sci. Adv., 5(10), p1413-1421.

-

Franck, P., L. Garnery, A. Loiseau, B. P. Oldroyd, H. R. Hepburn, M. Solignac, and J.-M. Cornuet, (2001), Genetic diversity of the honeybee in Africa: microsatellite and mitochondrial data, Heredity, 86, p420-430.

[https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2540.2001.00842.x]

- Gebretinsae, T., and Y. Tesfay, (2014), Honeybee colony marketing and its implications for queen rearing and beekeeping development in Tigray, Ethiopia, Int. J. Livest. Prod., 5(7), p117-128.

- Gebretsadik, T., and D. Negash, (2016), Honeybee production system, challenges and opportunities in selected districts of Gedeo zone, southern nation, nationalities and peoples regional state, Ethiopia, Int. J. Res. Knowl. Reposit., 4, p49-63.

- German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Promotion of wild coffee and honey as sustainable forest products. The Sheka biosphere reserve, https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/39619.htm Accessed on February 1, 2019.

- Gezahegne, T., (2001), Marketing of honey and beeswax in Ethiopia: past, present and perspective features, p78-88, in Proceedings of the third National Annual Conference of the Ethiopian Beekeepers Association (EBA), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ethiopia, Holeta Bee Research Centre, (2003), Annual Progress Report 2002/2003.

- Hartmann, I., (2004), The management of resources and marginalization in beekeeping Societies of South West Ethiopia, in Proc. Paper submitted to the conference: Bridge Scales and Epistemologies, Alexandria.

-

Ito, Y., (2014), Local honey production activities and their significance for local people: A case of mountain forest area of Southwestern Ethiopia.

[https://doi.org/10.14989/185109]

- Legesse, M., K. Wakjira, A. Bezabeh, D. Begna, and Addi A, (eds) (2012), Apiculture research achievements in Ethiopia, Oromia Agricultural Research Institute, Holeta Bee Research Center, Holeta, Ethiopia.

-

Lewoyehu, M., and M. Amare, (2019), Comparative assessment on selected physicochemical parameters and antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of honey samples from selected districts of the Amhara and Tigray regions, Ethiopia, Int. J. Food Sci., 2019, Article ID 4101695, 10 pages.

[https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4101695]

-

Meixner, M., M. Leta, N. Koeniger, and S. Fuchs, (2011), The honey bees of Ethiopia represent a new subspecies of Apis mellifera-Apis mellifera simensis n. ssp., Apidologie, 42, p425-437.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-011-0007-y]

- Mo, A., (2007), Livestock development master plan study phase I report-data collection and analysis, volume N-apiculture, ministry of agriculture and rural development (MoARD), Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- MoA and ILRI, (2013), Apiculture value chain vision and strategy for Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, Ministry of Agriculture and International Livestock Research Institute.

- Mohammed, N. A., (2002), Geographical races of the Honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) of the Northern Regions of Ethiopia, Rhodes University.

- Nicola, B., (2002), Taking the sting out of beekeeping, Arid Lands Information Network-East Africa (CD-Rom), Nairobi, Kenya.

- Oromia Livestock and Fishery Resource Development Bureau. Oromia regional state beekeeping potential.

- Radloff, S. E., and H. R. Hepburn, (1997), Multivariate analysis of honeybees, Apis mellifera L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) on the horn of Africa, Afr. Entomol., 5, p57-64.

- Ruttner, F., (1976), African races of honeybees, p1-20, in: Proc. Int. Beekeeping Congr, 25, Apimondia, Bucharest.

- Ruttner, F., (1985), Graded geographic variability in honey bees and environment, Pszczel. Zesz. Nauk., 29, p81-92.

-

Ruttner, F., (1988), Biogeography and taxonomy of honeybees, Springer, Berl.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-72649-1]

-

Sebsib, A., and T. Yibrah, (2018), Beekeeping practice, opportunities, marketing and challenges in Ethiopia: Review, DairyVet. Sci. J., 5(3), Article number: 555662.

[https://doi.org/10.19080/JDVS.2018.05.555662]

-

Serda, B., T. Zewudu, M. Dereje, and M. Aman, (2015), Beekeeping practices, production potential and challenges of bee keeping among beekeepers in Haramaya District, Eastern Ethiopia, J. Vet. Sci. Technol., 6, p255.

[https://doi.org/10.4172/2157-7579.1000255]

- Shenkute, A., Y. Getachew, D. Assefa, N. Adgaba, G. Ganga, and W. Abebe, (2012), Honey production systems (Apis mellifera L.) in Kaffa, Sheka and Bench-Maji zones of Ethiopia.

-

Shibru, D., G. Asebe, and E. Megersa, (2016), Identifying opportunities and constraints of beekeeping: the case of Gambella Zuria and Godere Weredas, Gambella Regional State, Ethiopia, Entomol. Ornithol. Herpetol., 5(3).

[https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0983.1000182]

- Shimelis, S., (2017), A diagnostic survey of honey production system and honey bee disease and pests in Ejere District, West Shoa Zone, Ethiopia, Addis Ababa University.

- Tadesse, G., and H. Kebede, (2014), Survey on honey production system, challenges and opportunities in selected areas of Hadya Zone, Ethiopia, J. Agric. Biotech. Sustain. Dev., 6(6), p60-66.

-

Teferi, K., (2018), Status of Beekeeping in Ethiopia-a review, J. Dairy Vet. Sci., 8(4), p555743.

[https://doi.org/10.19080/JDVS.2018.08.555743]

- Tesfaye, B., D. Begna, and M. Eshetu, (2017), Beekeeping practices, trends and constraints in Bale, South-eastern Ethiopia, J. Agric. Ext. Rural Dev., 9(4), p62-73.

- Tessega, B., (2009), Honeybee production and marketing systems, constraints and opportunities in Burie District of Amhara Region, Ethiopia, A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Animal Science and Technology, School of Graduate Studies, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, p24-45.

- World Bank Report, (2019), Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ethiopia/overview Accessed 24 June 2019.

- Yemane, N., and M. Taye, (2013), Honeybee production in the three Agro-ecological districts of Gamo Gofa zone of southern Ethiopia with emphasis on constraints and opportunities, Agric. Biol. J. N. Am., 4(5), p560-567.