양봉꿀벌 봉군에서 꿀벌응애 (Varroa destructor)와 중국가시응애 (Tropilaelaps mercedesae)에 대한 살비제 약제 효과 평가

Abstract

Varroa destructor and Tropilaelaps mercedesae are the major ectoparasitic mites of honey bee (Apis mellifera). This study evaluated the efficacy of the five commercial acaricides registered for Varroa mite control (Coumaphos, Amitraz, Thymol, Formic acid and Oxalic acid) during the autumn season in reproductive colonies. The five chemicals were applied twice and followed by Fluvalinate treatment. The rate of mite fall and overall control efficacy were assessed based on the sticky board and sugar-shaking counts. For Varroa mite, the study found that Formic acid achieved the highest efficacy (72.3%), while Oxalic acid showed the lowest (50.0%). For Tropilaelaps mite, Formic acid also had the highest efficacy (59.2%), and Coumaphos the lowest (37.9%). Notably, Coumaphos showed statistically significant difference in controlling Varroa mite compared to Tropilaelaps mites. These results underscore the need for species-specific mite control strategies and contribute to integrated pest management approaches in apiculture.

Keywords:

Honey bee, Varroa destructor, Tropilaelaps mercedesae, Acaricide, Susceptibility서 론

꿀벌은 화분매개를 통해 농작물 생산에 중요한 역할을 한다 (Morse and Calderone, 2000; Jung, 2008). 특히, 양봉꿀벌 (Apis melliferea)은 다양한 화분매개자 중 가장 많은 작물에 화분매개 서비스를 제공한다고 알려져 있다 (Breeze et al., 2014). 식물의 꽃을 방문하고 꽃가루를 매개하기 때문에 생물 다양성 유지 및 식량생산 기여 가치가 매우 높다 (Calderone, 2012). 또한, 전 세계 농작물의 70% 이상이 꿀벌 등에 의한 화분매개곤충에 의존한다 (Klein et al., 2007; Gallai et al., 2009).

미국에서는 2006년 꿀벌이 대규모로 사라지는 현상이 보고되었고, 이를 봉군붕괴현상 (Colony Collapse Disorder, CCD)이라 하였다 (vanEngelsdorp et al., 2007). 미국뿐만 아니라 유럽과 세계 도처에서 꿀벌이 사라지는 증상이 지속적으로 보고되고 있다 (Laurent et al., 2015). 우리나라에서는 월동 폐사와 소실 등 꿀벌 감소 문제가 발생하여 (Lee et al., 2022), 원인 파악과 대책을 요구하고 있다. 꿀벌 감소의 주된 원인으로 외부 기생성 응애류, 병원균, 영양 부족, 기후변화, 여왕벌 폐사 및 농약 피해 등을 지목하고 있다 (Johnson et al., 2010; Francis et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2013; de Jongh et al., 2022; Lee et al., 2022). 이러한 현상들은 한 요인에 의해서만 발생하는 것이 아니라, 여러 원인들이 복합적으로 작용하여 발생한다고 알려져 있다 (Oldroyd, 2007).

꿀벌 기생성 응애류는 꿀벌의 발육단계 전체에 걸쳐서 기생하며, 꿀벌의 지방체를 섭취하여 꿀벌 성장 및 활동을 방해한다 (Rosenkranz et al., 2010; Ramsey et al., 2019). 또한, 기생 과정에서 날개 변형 바이러스 (Deformed wing virus)와 꿀벌 급성 마비 바이러스 (Acute bee paralysis virus)와 같은 바이러스를 옮기고 (de Miranda et al., 2010; Mondet et al., 2014), 꿀벌 건강을 약화시켜 스트레스를 유발한다 (Forsgren and Fries, 2010; Francis et al., 2013).

국내에는 대표적으로 꿀벌응애 (Varroa destructor, Anderson and Trueman, 2000)와 중국가시응애 (Tropilaelaps mercedesae, Anderson and Morgan, 2007) 총 2종이 분포한다 (Woo and Lee, 1993; Jung et al., 2014). 꿀벌응애는 아시아권에서 재래꿀벌 (Apis cerana)에 기생하는 것으로 알려져 있었다 (Oudemans, 1904; Delfinado, 1963). 하지만 1970년대 이래 양봉꿀벌로 기주이동이 이루어져 (Roth et al., 2020) 지금은 전 세계적으로 양봉꿀벌을 사육하는 지역에 분포한다 (Matheson, 1995; Anderson and Roberts, 2013). 중국가시응애는 동남아에 서식하는 A. dorsata와 A. laborosa에 기생하였으나 (Delfinado-Baker et al., 1989), 1980년대 이후 양봉꿀벌로 기주이동하여 피해가 커지고 있다. 우리나라의 경우, 1992년에 중국에서부터 침입한 것으로 보고되었다 (Woo and Lee, 1993). 외부 기생성 응애류는 양봉꿀벌과의 공진화 기간이 짧기 때문에 저항성이 낮아 더 큰 피해를 줄 수 있다 (Warrit and Lekprayoon, 2010).

꿀벌응애는 꿀벌 번데기 기간에 기생하면서 번식하는 번식기와 성충의 몸에 붙어서 이동하는 편승기로 나뉜다 (Jung, 2015; Traynor et al., 2020). 암컷 꿀벌응애는 꿀벌 종령 애벌레가 번데기 되기 직전에 소방에 들어간다. 소방이 봉개되면 60~70시간 후에 산란을 시작하며 (Martin, 1994; Garrido and Rosenkranz, 2003), 30시간 간격으로 산란한다 (Ifantidis, 1983). 그리고 양봉꿀벌의 일벌 번데기에서 0.7~1.5마리의 성숙한 암컷 2세대를 낳으며, 수벌 번데기에는 1.6~2.5마리의 2세대 암컷을 낳는다 (Rosenkranz et al., 2010). 꿀벌 성충이 출방할 때 꿀벌응애와 함께 나오게 되며, 꿀벌 성충에 기생하는 편승기가 시작된다. 이때, 꿀벌응애는 꿀벌 성충의 배판 사이에 주로 기생한다 (de D’Aubeterre et al., 1999). 그리고 꿀벌응애가 섭식하는 부위는 꿀벌응애의 타액으로 인해 상처가 아물지 않는다 (Richards et al., 2011). 중국가시응애의 생활사는 꿀벌응애와 매우 유사하다. 꿀벌응애는 30시간 간격으로 알을 낳는 데에 비해 중국가시응애는 24시간 간격으로 알을 낳는다 (Woyke, 1987). 성충에 기생하는 기간 또한 꿀벌응애는 평균 27일이며 중국가시응애는 1~3일로 매우 짧다 (Woyke, 1987; Rinderer et al., 1994). 따라서 중국가시응애가 꿀벌응애보다 번식 주기가 빨라 꿀벌 봉군 내 밀도 증가 속도가 빠를 수 있다 (Anderson and Morgan, 2007). 그리고 꿀벌의 수명 감소 (Khongphinitbunjong et al., 2015, 2016) 및 체내 총 단백질 함량을 감소시켜 (Naji and Kumar, 2014) 꿀벌 개체수의 감소를 초래할 수 있다 (Camphor et al., 2005).

두 종의 감염 밀도는 지리적 요인과 기후적 요인에 따라 달라지는데, 태국과 아프가니스탄 그리고 베트남에서는 중국가시응애의 밀도가 꿀벌응애보다 높다 (Burgett et al., 1983). 반면에 한국은 꿀벌응애의 밀도가 중국가시응애에 비해 더 높다 (Jung et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2005). 지구온난화로 인해 우리나라는 전 세계 기온 상승 대비 2배 이상 증가하였고 (IPCC, 2007; Jung 2015), 그로 인해 남방계 해충인 중국가시응애의 밀도가 높아질 가능성이 있다. 실제로 일부 양봉장에서는 중국가시응애의 밀도가 꿀벌응애의 밀도를 넘어섰다는 보고가 있으며 (Choi et al., 2014), 점차 중국가시응애의 피해가 심각해지는 추세이다.

꿀벌 기생성 응애류를 방제하기 위하여 양봉농가에서는 합성화합물과 천연물을 이용한 방제, 생태적 방제법을 동원한다 (Jung and Kim, 2008). 합성화합물에는 플루발리네이트, 아미트라즈, 쿠마포스 등이 대표적이다 (Tihelka, 2018). 이 중 피레스로이드계인 플루발리네이트는 간편한 사용법으로 인해 농가에서 장기간 동안 집중적으로 사용되어왔다 (Gracia-Salinas et al., 2006; Jeong et al., 2016). 그로 인해 저항성 발현 문제가 보고되었으며, 전 세계적으로 저항성 문제가 심화되고 있다 (Elzen et al., 1998, 1999; Kamler et al., 2016). 우리나라 역시 플루발리네이트류 의존성이 높은 상태이다 (Jeong et al., 2016). 그로 인해 농가에서는 약제 저항성으로 인한 낮은 응애 방제율로 어려움을 호소하고 있다 (Kim and Lee, 2022). 따라서 피레스로이드계를 대체할 수 있는 살비제 개발이 절실하다. 그리고 꿀벌 기생성 응애류와 관련된 연구개발은 국내외 대부분 꿀벌응애를 대상으로 수행되어 왔다 (Roberts et al., 2020). 중국가시응애는 아시아에 국한되어 발생하여 상대적으로 생리 및 생태 방제 연구가 미비한 실정이다. 중국가시응애에 대한 일부 약제 (플루메트린, 플루발리네이트, 쿠마포스 및 개미산)의 방제 효과에 관한 연구가 진행되었다 (Wilde et al., 2000; Kongpitak et al., 2008; Pettis et al., 2017). 하지만 티몰, 개미산 등이 온도, 습도에 따라 방제 효과가 달라진다는 선행연구들을 비추어 보았을 때 (Underwood and Currie, 2003; Bacandritsos et al., 2007), 선행연구들이 동남아시아 국가에서 진행되어 국내 기후 조건에서 적용하는 데에는 한계가 있다.

본 연구는 우리나라에 꿀벌응애 방제약제로 등록된 5종 살비제의 국내 상황에서 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애에 대한 방제 효과를 검토하고자 하였다. 합성화학농약인 아미트라즈와 쿠마포스, 유기산인 개미산과 옥살산, 식물추출물인 티몰을 사용하였다. 꿀벌응애 방제제로 등록된 약제들이 플루발리네이트 저항성 집단으로 변한 국내 꿀벌응애에 방제 효과가 있는지, 그리고 중국가시응애에도 비슷한 수준의 방제 효과가 있는지를 검토하고자 하였다.

재료 및 방법

1. 공시충

시험은 2023년 9월 21일부터 10월 11일까지 수행하였다. 시험 봉군은 안동대학교 시험양봉장 (36°32ʹ41ʺN, 128°48ʹ04ʺE)에서 사육하는 양봉꿀벌을 이용하였고, 처리구별 5 반복을 위해 총 25개의 봉군을 선발하였다. 그리고 4매 이상의 정상적으로 산란이 진행되는 봉군을 사용하였고, 시험 진행 전 4개월 동안 응애방제를 하지 않았다.

2. 공시 살비제

시험에는 아미트라즈, 쿠마포스, 개미산, 옥살산, 티몰 그리고 약제 효과 평가를 위한 후속 처리로 플루발리네이트를 사용하였다. 각 약제의 유효성분은 아미트라즈 12.5%, 쿠마포스 3.2%, 개미산 76.5%, 옥살산 3.5%, 티몰 2.1%이다. 아미트라즈는 해당 약제 1 mL를 물 1000 mL에 희석하여 소비 사이에 4 mL씩 처리하였으며, 쿠마포스 1 mL를 물 50 mL에 희석하여 봉군당 25 mL를 분무하였다. 개미산은 봉군당 1개의 마이트케이 제품을 소비 위에 배치하였으며, 옥살산 35 g을 50% 자당 수용액 1000 mL에 희석하여 소비 사이에 5 mL씩 처리하였다. 티몰 20 mL를 물 980 mL에 희석하여 소비 사이에 50 mL씩 주사기로 흘림 처리하였다 (Table 1).

3. 꿀벌 외부 기생성 응애류 약제 방제 효과 평가

9월 21일에 설탕분말법을 이용하여 약제 처리 전 꿀벌 외부 기생성 응애류에 대한 꿀벌 성충의 감염률을 확인하였다. Kim and Jung (2008)을 참고하여 봉군당 100여 마리의 성충 꿀벌을 채취 후 설탕분말법을 진행하여 꿀벌 외부 기생성 응애류 개체수를 파악하였다. 그리고 설탕분말법은 봉군 당 3 반복하였다. 같은 방법으로 시험 약제 처리가 끝난 10월 9일에 약제 처리 후 꿀벌 성충의 응애 감염률 조사를 위해 설탕분말법을 진행하였다.

9월 21일 약제 처리 전, 탈락하는 응애수를 파악하기 위하여 벌통 바닥에 바셀린은 도포한 판을 설치하였다. 9월 22일 1차 약제 처리를 진행하였고, 21일에 설치한 판은 수거하였다. 그리고 바셀린을 도포한 새로운 판을 재설치하였다. 약제 처리 이후 1일, 3일, 5일 간격으로 바닥에 설치한 판을 수거 및 재설치하였고, 수거한 판은 실험실로 가져와 판에 떨어진 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애의 개체수를 확인하였다. 2차 약제 처리는 10월 3일에 하였고 1차 약제 처리와 마찬가지로 약제 처리 후 1일, 3일, 5일 간격으로 벌통 바닥에 바셀린을 바른 판을 설치 및 수거하였다. 그리고 수거한 판에 떨어져 있는 꿀벌 외부 기생성 응애류의 개체수를 확인하였다. 약제 방제 효과 평가를 위해 10월 9일에 플루발리네이트를 후속 처리로 진행하였고, 마찬가지로 바셀린을 바른 판을 바닥에 설치하였다. 10월 9일에 설치한 판은 10월 11일에 수거하여 꿀벌 외부 기생성 응애류의 개체수를 파악하였다.

Dietemann et al. (2013)을 참고하여 방제 효과를 계산하였으며, 해당 식은 다음과 같다.

MR: 응애 약제 처리 후 사망 응애수

NMKT: 약제 처리로 죽은 응애수

NMKFT: 후속 처리로 죽은 응애 수

두 응애 종에 대한 약제 방제 효과와 약제 처리 전, 후의 성충 감염률 차이를 t-test를 사용하여 분석하였고, 정규분포하지 않는 자료는 Mann-Whitney U test를 사용하여 분석하였다. 분석은 SPSS software (IBM Armonk, NY, USA)을 이용하였다.

결 과

1. 꿀벌 성충의 응애 감염률

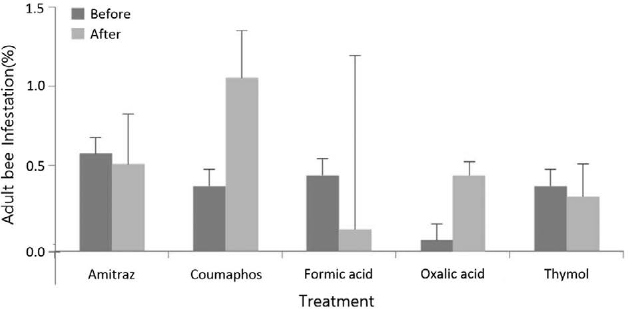

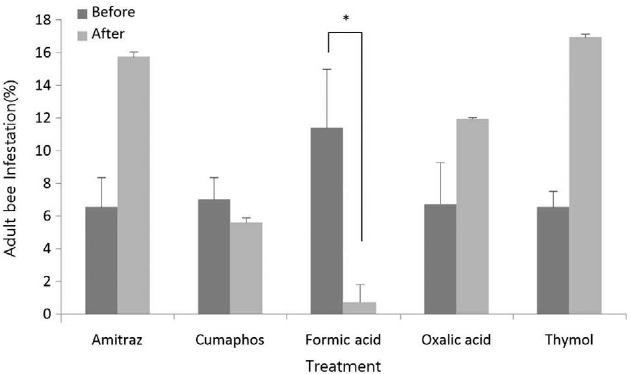

쿠마포스와 개미산 처리구에서는 꿀벌응애 감염률이 감소하였다. 그리고 아미트라즈, 옥살산, 티몰 처리구에서는 꿀벌응애 감염률이 증가한 것을 확인할 수 있었으며, 개미산에서만 통계적으로 유의미한 차이가 나타났다 (t-test, t=5.437, P<0.05, Fig. 1). 중국가시응애의 경우에는 쿠마포스와 옥살산에서 처리 후 감염 비율이 증가하였고 아미트라즈, 개미산, 티몰에서는 감소하였다. 그러나 모두 통계적으로 유의미한 차이는 나타나지 않았다 (Fig. 2).

Infestation rate (Mean±SE%) of Varroa destructor on the body of adult honey bees before and after treatments, determined by sugar shaking method. All colonies received Fluvalinate application after twice applications of each chemical treatment. The bars indicate mean±standard error (SE). *indicates the significant difference before and after treatments with t-test, P<0.05.

2. 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애에 대한 약제 방제 효과

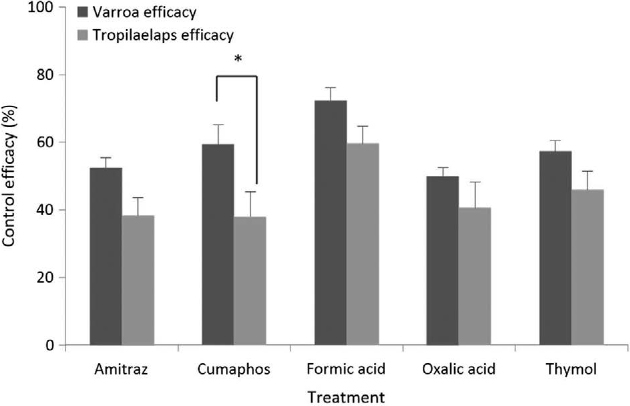

약제 처리 후 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애에 대한 약제 방제 효과는 다음과 같다. 꿀벌응애에 대한 아미트라즈, 쿠마포스, 개미산, 옥살산, 티몰의 방제 효과는 각 52.5%, 59.4%, 72.3%, 50.0%, 그리고 57.3%였다. 중국가시응애에 대한 아미트라즈, 쿠마포스, 개미산, 옥살산, 티몰의 방제 효과는 각 38.4%, 37.9%, 59.6%, 40.6%, 그리고 45.9%였다.

방제 효과는 전반적으로 중국가시응애에서 낮았다. 그러나 아미트라즈, 개미산, 옥살산 그리고 티몰에서는 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애의 방제 효과 사이엔 통계적으로 유의미한 차이는 나타나지 않았으나, 쿠마포스에서는 통계적으로 유의미한 차이가 나타났다 (t-test, t=3.368, P<0.01, Fig. 3).

The control efficacy (Mean±SE%) of Amitraz, Coumaphos, Formic acid, Oxalic acid and Thymol treatment against Varroa destructor and Tropilaelaps mercedesae in the Apis mellifera colony. Counts of all Varroa and Tropilaelaps mites were counted after one day after the first and second application of these products. final application of Fluvalinate in colonies. The bars indicate mean±standard error (SE). *The horizontal brackets indicate the efficacy comparison between Varroa and Tropilaelaps for the Coumaphos treatment; *P<0.05.

고 찰

우리나라에 꿀벌응애 방제 약제로 등록되어 있는 살비제들은 전반적으로 중국가시응애에 비해 꿀벌응애 방제에 효과가 더 높았다. 사용한 약제 중 개미산은 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애 모두 가장 높은 방제 효과가 나타났다. 쿠마포스는 중국가시응애보다는 꿀벌응애에 더 높은 방제 효과가 나타났다. 이는 쿠마포스가 꿀벌응애에 효과가 있는 반면, 중국가시응애에서는 상대적으로 낮은 효과가 나타난다는 선행연구와도 일치한다 (Wongsiri et al., 1989). 이러한 결과는 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애의 섭식 행동의 차이에서 오는 것으로 보인다. 꿀벌응애는 꿀벌 성충에서도 기생이 가능하다 (Garrido and Rosenkranz, 2003). 반면에, 중국가시응애는 꿀벌 성충에서 기생하지 않고 소비 위를 방랑하는 습성이 있다 (Kumar et al., 1993). 중국가시응애는 대부분의 시간을 소방 내부나 소비 위에 머물기 때문에, 꿀벌 성충에 부착된 약제가 응애 방제에 미치는 영향은 미미할 수 있다 (Pettis et al., 2017). 개미산은 다른 약제들에 비해 높은 효과가 나타났는데, 꿀벌응애에서는 72.3%, 중국가시응애에서는 59.2%의 방제 효과가 나타났다. 개미산은 훈증으로 작용을 하므로, 성충에게만 작용하지 않고 번데기 내부 및 소비에서 방랑하고 있는 중국가시응애에도 효과가 미치는 약제이기 때문인 것으로 보인다 (Fries, 1993).

시험의 약제 방제 효과는 선행연구들에 비하여 전반적으로 낮은 약제 방제 효과를 확인할 수 있었다 (Table 2). 이는 번데기가 있는 봉군을 대상으로 시험을 진행하였기 때문으로 판단된다. 정확한 약제 효과 평가를 위해서는 번데기가 없는 상태에서 진행하여야 한다. 하지만 시험 시기가 겨울벌을 생산하는 시기였다. 번데기가 존재하는 봉군상태는 가을 기간의 양봉 농가들의 현실 상황을 반영한 결과로 볼 수 있다 (Lee et al., 2022). 더불어, Dietemann et al. (2013)에 서술되어 있는 약제 효과 평가법에는 약제 처리일 기준 14일 이상 관찰하여야 한다고 말한다. 하지만 양봉 농가에서 단시간에 약효를 높히기 위해 약량을 늘리는 행위를 하고 있다 (Woo et al., 1994). 이는 단기간 동안 응애를 방제하길 원하는 것으로 볼 수 있다. 따라서 그에 따른 단기적인 기간에 대한 방제 효과를 알아보기 위해 관찰 기간을 짧게 설정하였다.

Comparison of the control efficacy of various treatment against Varroa destructor and Tropilaelaps mercedesae from the published literatures and this study

그리고 후속 처리로 선발한 플루발리네이트는 전체 꿀벌 기생성 응애류의 개체군을 측정하고 약제 효과를 도출하기 위하여 사용하였다. 시험에 사용된 화학성분과 다른 성분의 후속 처리가 필요했기 때문에 선정하였고 (Dietemann et al., 2013), 플루발리네이트는 이미 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애에 대하여 저항성이 보고된 바가 있다 (Elzen et al., 1998, 1999; Sammataro et al., 2005; Gracia-Salinas et al., 2006). 그러나 모기과에 속하는 Anopheles속에서 저항성이 보고된 피레스로이드계 약제를 비피레스로이드계인 약제와 함께 사용하였을 때는 저항성이 감소했다는 보고가 있다 (Barker et al., 2023). 따라서, 같은 피레스로이드계인 플루발리네이트 역시 저항성 회복에 일정 효과가 있을 가능성이 존재한다. 그러므로 본 연구에서 약제의 효과 평가에 큰 영향을 미치지 않은 것으로 판단된다.

꿀벌 성충의 꿀벌응애 감염률은 아미트라즈, 옥살산, 티몰을 처리한 처리구에서 증가하였다. 일벌의 생활사는 알 기간 3일, 애벌레 기간 6일, 번데기 기간은 12일이며 (Kevan, 2007), 본 시험의 사전, 사후 설탕분말법 사이 기간은 18일이다. 그렇기 때문에 사전 설탕분말법을 진행 할 당시 번데기 내에 있던 응애들이 꿀벌 성충이 출방하면서 함께 나와 감염률이 증가한 것으로 보인다. 아미트라즈, 옥살산, 티몰 중 옥살산은 번데기가 없는 기간에 효과적이라는 선행연구가 있다 (Charriere and Imdorf, 2002; Gregorc and Planinc, 2001; Gregorc et al., 2017). 이는 옥살산이 번데기 내부에 있는 응애를 죽이지 못함을 시사한다 (Jack et al., 2020). 따라서 번데기 내부에 존재하는 꿀벌응애를 죽이지 못한 것이 성충 꿀벌의 응애 감염률이 증가하는 원인으로 보인다.

설탕분말법을 이용하여 성충의 응애 감염률을 조사하였을 때, 처리구마다 검출된 꿀벌응애는 평균적으로 약제 처리 전은 7.6마리, 약제 처리 이후에는 10.2마리였다. 중국가시응애의 경우에는 약제 처리 전에는 0.4마리, 약제 처리 이후에는 0.5마리로 검출된 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애의 개체수 차이가 나는 것을 확인할 수 있었다. 설탕분말법은 꿀벌 성충에 붙어있는 응애를 떨어뜨려 감염률을 확인하는 방법이다 (Bąk et al., 2009). 앞서 말한 것 처럼 꿀벌응애는 성충에 편승이 가능하지만 중국가시응애는 편승하지 못한다 (Kumar et al., 1993; Garrido and Rosenkranz, 2003). 그렇기 때문에 설탕분말법은 꿀벌응애 밀도 추정에는 유효하나 중국가시응애 밀도 조사 방법으로는 적절치 않다. 중국가시응애의 최다 발생기는 7, 8월로 시험 진행 기간인 9월과 차이가 있었다 (Choi et al., 2014). 응애 방제 효과 검토는 최다 발생기를 중심으로 하는 것이 효율적이다. 그리고 본 시험에 사용된 봉군들은 6월에 인공 분봉한 봉군이다. 여름철 인공 분봉이 중국가시응애의 밀도를 낮출 수 있다는 Pettis et al. (2017)의 연구 결과 또한 중국가시응애의 낮은 검출을 뒷받침한다. 따라서 응애의 성충 감염률과 약제 방제 효과를 종합적으로 보았을 때, 국내 조건에서 두 응애에 대해 모두 효과가 좋은 약제는 개미산임을 확인할 수 있었다. 더불어 약제 방제 효과 차이가 두 종의 기생성 응애류에 대해 다르게 나타났기 때문에, 방제 대상에 대해 적합한 약제를 사용하는 데 참고 자료로 활용할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

적 요

꿀벌응애 (Varroa destructor)와 중국가시응애 (Tropilaelaps mercedesae)는 양봉꿀벌 (Apis mellifera)의 주요 외부 기생성 응애류이다. 이번 연구는 가을철 꿀벌응애 방제용으로 등록된 시판 살비제 5종을 대상으로 산란이 진행되고 있는 군집에서의 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애에 대한 효과를 평가하였다. 5종 약제를 2회 처리한 후 플루발리네이트를 처리하였다. 약제 효과는 벌통 바닥에 설치한 판과 설탕분말법을 기준으로 평가하였다. 꿀벌응애에서는 약제 중 개미산이 가장 높은 방제 효과 (72.3%)가 나타났고, 가장 낮은 방제 효과는 옥살산 (50.0%)이었다. 중국가시응애의 경우에도 개미산이 가장 높은 방제 효과 (59.8%)를 보였고, 쿠마포스가 가장 낮은 방제 효과 (37.9%)를 보였다. 그리고 쿠마포스에서 꿀벌응애와 중국가시응애의 방제 효과는 통계적으로 유의미한 차이가 나타났다. 이러한 결과는 꿀벌 기생성 응애류에 대한 방제 전략의 필요성을 강조하고 양봉농가의 종합적인 해충 관리에 도움이 될 수 있다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 한국연구재단 중점연구소 지원사업 (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862)과 농촌진흥청 스마트양봉 연구과제 (RS-2023-00232847)의 지원으로 수행되었습니다.

References

- Anderson, D. L. and J. W. H. Trueman. 2000. Varroa jacobsoni (Acari: Varroidae) is more than one species. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 24: 165-189.

-

Anderson, D. L. and M. J. Morgan. 2007. Genetic and morphological variation of bee-parasitic Tropilaelaps mites (Acari: Laelapidae): new and re-defined species. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 43: 1-24.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-007-9103-0]

-

Anderson, D. L. and J. M. Roberts. 2013. Standard methods for Tropilaelaps mites research. J. Apic. Res. 52(4): 1-16.

[https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.21]

-

Bacandritsos, N., I. Papanastasiou, C. Saitanis, A. Nanetti and E. Roinioti. 2007. Efficacy of repeated trickle applications of oxalic acid in syrup for varroosis control in Apis mellifera: Influence of meteorological conditions and presence of brood. Vet. Parasitol. 148(2): 174-178.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.06.001]

- Bąk, B., J. Wilde, M. Siuda and M. Kobylińska. 2009. Comparison of two methods of monitoring honeybee infestation with Varroa destructor mite. Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences-SGGW. Anim. Sci. (46): 33-38.

-

Barker, T. H., J. C. Stone, S. Hasanoff, C. Price, A. Kabaghe and Z. Munn. 2023. Effectiveness of dual active ingredient insecticide-treated nets in preventing malaria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 18(8): e0289469.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0289469]

-

Breeze, T. D., B. E. Vaissière, R. Bommarco, T. Petanidou, N. Seraphides, L. Kozák and S. G. Potts. 2014. Agricultural policies exacerbate honeybee pollination service supply-demand mismatches across Europe. PLoS One 9(1): e82996.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082996]

-

Burgett, M., P. Akratanakul and R. A. Morse. 1983. Tropilaelaps clareae: a parasite of honeybees in south-east Asia. Bee World 64(1): 25-28.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1983.11097904]

-

Calatayud-Vernich, P., F. Calatayud, E. Simó and Y. Picó. 2018. Pesticide residues in honey bees, pollen and beeswax: Assessing beehive exposure. Environ. Pollut. 241: 106-114.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.062]

-

Calderone, N. W. 2012. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992-2009. PLoS One 7(5): e37235.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037235]

- Camphor, E. S. W., A. A. Hashmi, W. Ritter and I. D. Bowen. 2005. Seasonal changes in mite (Tropilaelaps clareae) and honeybee (Apis mellifera) populations in Apistan treated and untreated colonies. Apiacta 40(2): 005.

-

Charriére, J. D. and A. Imdorf. 2002. Oxalic acid treatment by trickling against Varroa destructor: recommendations for use in central Europe and under temperate climate conditions. Bee World 83(2): 51-60.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.2002.11099541]

-

Choi, Y. S., M. L. Lee, H. S. Lee, H. K. Kim, K. H. Byeon, M. Y. Yoon, A. R. Kang, T. V. Toan, I. P. Hong and S. O. Woo. 2014. Morphological analysis and determination of interference competition between two honeybee mites: Varroa destructor and Tropilaelaps clareae (Acari: Varroidae and Laelapidae). J. Apic. 29(4): 327- 332.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2014.11.29.4.327]

-

de D̓Aubeterre, J. P., D. D. Myrold, L. A. Royce and P. A. Rossignol. 1999. A scientific note of an application of isotope ratio mass spectrometry to feeding by the mite, Varroa jacobsoni Oudemans, on the honeybee, Apis mellifera L. Apidologie 30(4): 351-352.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:19990413]

-

de Jongh, E. J., S. L. Harper, S. S. Yamamoto, C. J. Wright, C. W. Wilkinson, S. Ghosh and S. J. Otto 2022. One Health, One Hive: A scoping review of honey bees, climate change, pollutants, and antimicrobial resistance. PLoS One 17(2): e0242393.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242393]

-

Delfinado, M. D. 1963. Mites of the honeybee in South-East Asia. J. Apic. Res. 2(2): 113-114.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1963.11100070]

- Delfinado-Baker, M., E. W. Baker and A. C. G. Phoon. 1989. Mites (Acari) associated with bees (Apidae) in Asia, with description of a new species. An. Bee. J. 129(9): 609-613.

-

de Miranda, J. R., G. Cordoni and G. Budge. 2010. The acute bee paralysis virus-Kashmir bee virus-Israeli acute paralysis virus complex. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103: S30- S47.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.06.014]

-

Dietemann, V., F. Nazzi, S. J. Martin, D. L. Anderson, B. Locke, K. S. Delaplane, Q. Wauquiez, C. Tannahill, E. Frey, B. Ziegelmann, P. Rosenkranz and J. D. Ellis. 2013. Standard methods for varroa research. J. Apic. Res. 52(1): 1-54.

[https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.09]

-

Eguaras, M., M. A. Palacio, C. Faverin, M. Basualdo, M. L. Del Hoyo, G. Velis and E. Bedascarrasbure. 2003. Efficacy of formic acid in gel for Varroa control in Apis mellifera L.: importance of the dispenser position inside the hive. Vet. Parasitol. 111(2-3): 241-245.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00377-1]

- Elzen, P. J., F. A. Eischen, J. B. Baxter, J. Pettis, G. W. Elzen and W. T. Wilson. 1998. Fluvalinate resistance in Varroa jacobsoni from several geographic locations. Am. Bee J. 138: 674-676.

-

Elzen, P. J., F. A. Eischen, J. R. Baxter, G. W. Elzen and W. T. Wilson. 1999. Detection of resistance in US Varroa jacobsoni Oud. (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) to the acaricide fluvalinate. Apidologie 30: 13-17.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:19990102]

-

Elzen, P. J., J. R. Baxter, M. Spivak and W. T. Wilson. 2000. Control of Varroa jacobsoni Oud. resistant to fluvalinate and amitraz using coumaphos. Apidologie 31(3): 437-441.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2000134]

-

Forsgren, E. and I. Fries. 2010. Comparative virulence of Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis in individual European honey bees. Vet. Parasitol. 170(3-4): 212-217.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.02.010]

-

Francis, R. M., S. L. Nielsen and P. Kryger. 2013. Varroa-Virus Interaction in Collapsing Honey Bee Colonies. PLoS ONE 8.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057540]

- Fries, I. 1993. Varroa in cold climates: population dynamics, biotechnical control and organic acids.

-

Gallai, N., J. M. Salles, J. Settele and B. E. Vaissière. 2009. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecol. Econ. 68(3): 810-821.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014]

-

Garrido, C. and P. Rosenkranz. 2003. The reproductive program of female Varroa destructor mites is triggered by its host, Apis mellifera. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 31: 269- 273.

[https://doi.org/10.1023/B:APPA.0000010386.10686.9f]

-

Giacomelli, A., M. Pietropaoli, A. Carvelli, F. Iacoponi and G. Formato. 2016. Combination of thymol treatment (Apiguard®) and caging the queen technique to fight Varroa destructor. Apidologie 47(4): 606-616.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-015-0408-4]

-

Gracia-Salinas, M. J., M. Ferrer-Dufol, E. Latorre-Castro, C. Monero-Manera, J. A. Castillo-Hernández, J. Lucientes-Curd and M. A. Peribanez-Lopez. 2006. Detection of fluvalinate resistance in Varroa destructor in Spanish apiaries. J. Apic. Res. 45(3): 101-105.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2006.11101326]

-

Gregorc, A., M. Alburaki, C. Werle, P. R. Knight and J. Adamczyk. 2017. Brood removal or queen caging combined with oxalic acid treatment to control varroa mites (Varroa destructor) in honey bee colonies (Apis mellifera). Apidologie 48: 821-832.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-017-0526-2]

-

Gregorc, A. and I. Planinc. 2001. Acaricidal effect of oxalic acid in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies. Apidologie 32(4): 333-340.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2001133]

-

Gregorc A and I. Planinc. 2004. Dynamics of falling Varroa mites in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies following oxalic acid treatments. Acta Vet. Brno. 73(3): 385-391.

[https://doi.org/10.2754/avb200473030385]

-

Ifantidis, M. D. 1983. Ontogenesis of the mite Varroa jacobsoni in worker and drone honeybee brood cells. J. Apic. Res. 22(3): 200-206.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1983.11100588]

-

Jack, C. J., E. van Santen and J. D. Ellis. 2020. Evaluating the efficacy of oxalic acid vaporization and brood interruption in controlling the honey bee pest Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 113(2): 582-588.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/toz358]

-

Jeong, S., C. Lee, D. Kim and C. Jung. 2016. Questionnaire study on the overwintering success and pest management of honeybee and damage assessment of vespa hornets in Korea. J. Apic. 31: 201-210.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2016.09.31.3.201]

-

Johnson, R. M., M. D. Ellis, C. A. Mullin and M. Frazier. 2010. Pesticides and honey bee toxicity-USA. Apidologie 41: 312-331.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido/2010018]

- Jung, C. 2008. Economic Value of Honeybee Pollination on Major Fruit and Vegetable Crops in Korea. J. Apic. 23(2): 147-152.

-

Jung, C. 2015. Simulation Study of Varroa Population under the Future Climate Conditions. J. Apic. 30(4): 349- 358.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2015.11.30.4.349]

- Jung, C. and D. Kim. 2008. A Population Model of the Varroa Mite, Varroa destructor on Adult Honeybee in the Colony I. Exponential Poulation Growth. J. Apic. 23(4): 269-273.

-

Jung, C., D. Kim and J. Kim. 2014. Redefined Species of Tropilaelaps mercedesae Anderson and Morgan, 2007 (Acari: Laelapidae) Parasitic on Apis mellifera in Korea. J. Apic. 29(4): 217-221.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2014.11.29.4.217]

- Jung, J. K., M. Y. Lee and Y. I. Mah. 2000. Infestation of Varroa jacobsoni and Tropilaelaps clareae in some apiaries during spring and fall seasons, 1999-2000 in South Korea. Korean J. Apicult. 15(15): 141-145.

-

Kamler, M., M. Nesvorna, J. Stara, T. Erban and J. Hubert. 2016. Comparison of tau-fluvalinate, acrinathrin, and amitraz effects on susceptible and resistant populations of Varroa destructor in a vial test. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 69: 1-9.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-016-0023-8]

- Kevan, P. G. 2007. Bees, biology & management. 345. Enviroquest Ltd. Cambridge, Ontario, Canada.

-

Khongphinitbunjong, K., L. I. De Guzman, M. R. Tarver, T. E. Rinderer and P. Chantawannakul. 2015. Interactions of Tropilaelaps mercedesae, honey bee viruses and immune response in Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 54(1): 40-47.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2015.1041311]

-

Khongphinitbunjong, K., P. Neumann, P. Chantawannakul and G. R. Williams. 2016. The ectoparasitic mite Tropilaelaps mercedesae reduces western honey bee, Apis mellifera, longevity and emergence weight, and promotes Deformed wing virus infections. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 137: 38-42.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2016.04.006]

- Kim, D. and C. Jung. 2008. Evaluation of Chemical Susceptibility for the Ectoparasitic Mite Varroa destructor Anderson and Trueman (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) in Honeybee (Apis mellifera L.). J. Apic. 23(4): 259-268.

-

Kim, Y. H. and S. H. Lee. 2022. Current Status of Fluvalinate Resistance in Varroa destructor in Korea and Suggestion for Possible Solution. J. Apic. 37(3): 301-313.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2022.09.37.3.301]

-

Klein, A. M., B. E. Vaissière, J. H. Cane, I. Steffan-Dewenter, S A. Cunningham, C. Kremen and T. Tscharntke. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. P. Roy. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 274(1608): 303- 313.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721]

- Kongpitak, P., G. Polgár, J. Heine and A. Bayer Healthcare. 2008. The efficacy of Bayvarol® and Check Mite® in the control of Tropilaelaps mercedesae in the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) in Thailand. Apıacta 43: 12-16.

-

Kumar, N. R., R. Kumar, J. Mbaya and R. W. Mwangi. 1993. Tropilaelaps clareae found on Apis mellifera in Africa. Bee World 74(2): 101-102.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1993.11099168]

- Laurent, M., P. Hendrikx, M. Ribiere-Chabert and M. P. Chauzat. 2015. A pan-European epidemiological study on honeybee colony losses 2012-2014. EPILOBEE Report.

- Lee, M. L., Y. M. Park, M. Y. Lee, Y. S. Kim and H. K. Kim. 2005. Density Distributino of Parasitic Mites, Varroa destroctor Anderson and Trueman and Tropilaelaps clarea Delfinado and Baker, on Honeybee Pupae (Apis mellifera L.) in Autumn Season in Korea. J. Apic. 20(2): 103-108.

-

Lee, S. J., S.-H. Kim, J. Lee, J. H. Kang, S. M. Lee, H. J. Park, J. Nam and C. Jung. 2022. Impact of Ambient Temperature Variability on the Overwintering Failure of Honeybees in South Korea. J. Apic. 37(3): 331-347.

[https://doi.org/10.17519/apiculture.2022.09.37.3.331]

- Mahmood, R., E. S. Wagchoure, S. Raja, G. Sarwar and M. Aslam. 2011. Effect of thymol and formic acid against ectoparasitic brood mite Tropilaelaps clareae in Apis mellifera colonies. Pakistan J. Zool. 43(1): 91-95.

- Mahmood, R., E. S. Wagchoure, S. Raja and G. Sarwar. 2012. Control of Varroa destructor using oxalic acid, formic acid and bayvarol strip in Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies. Pakistan J. Zool. 44(6): 1473-1477.

-

Martin, S. J. 1994. Ontogenesis of the mite Varroa jacobsoni Oud. in worker brood of the honeybee Apis mellifera L. under natural conditions. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 18(2): 87- 100.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055033]

- Matheson, A. 1995. First documented findings of Varroa jacobsoni outside its presumed natural range. Apiacta 30(1): 1-8

-

Mondet, F., J. R. de Miranda, A. Kretzschmar, Y. Le Conte and A. R. Mercer. 2014. On the front line: quantitative virus dynamics in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies along a new expansion front of the parasite Varroa destructor. PLoS Pathog. 10(8): e1004323.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1004323]

- Morse, R. A. and N. W. Calderone. 2000. The value of honey bees as pollinators of US crops in 2000. Bee Culture 128(3): 1-15.

-

Negi, J. and N. R. Kumar. 2014. Changes in protein profile and RNA content of Apis mellifera worker pupa on parasitization with Tropilaelaps clareae. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 6: 693-695.

[https://doi.org/10.31018/jans.v6i2.519]

-

Oldroyd, B. P. 2007. What̓s killing American honey bees?. PLoS Biology 5(6): e168.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0050168]

- Oudemans, A. C. 1904. On a new genus and species of parasitic acari. Notes from the Leyden Museum, 24(4): 216- 222.

-

Pettis, J. S., R. Rose and V. Chaimanee. 2017. Chemical and cultural control of Tropilaelaps mercedesae mites in honeybee (Apis mellifera) colonies in Northern Thailand. PLoS One 12(11): e0188063.

[https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0188063]

-

Ramsey, S. D., R. Ochoa, G. Bauchan, C. Gulbronson, J. D. Mowery, A. Cohen and D. van Engelsdorp. 2019. Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honey bee fat body tissue and not hemolymph. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 116(5): 1792-1801.

[https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1818371116]

-

Richards, E. H., B. Jones and A. Bowman. 2011. Salivary secretions from the honeybee mite, Varroa destructor: effects on insect haemocytes and preliminary biochemical characterization. Parasitology 138(5): 602-608.

[https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182011000072]

-

Rinderer, T. E., B. P. Oldroyd, C. Lekprayoon, S. Wongsiri, C. Boonthai and R. Thapa. 1994. Extended survival of the parasitic honey bee mite Tropilaelaps clareae on adult workers of Apis mellifera and Apis dorsata. J. Apic. Res. 33(3): 171-174.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1994.11100866]

-

Roberts, J. M., C. N. Schouten, R. W. Sengere, J. Jave and D. Lloyd. 2020. Effectiveness of control strategies for Varroa jacobsoni and Tropilaelaps mercedesae in Papua New Guinea. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 80: 399-407.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10493-020-00473-7]

-

Rosenkranz, P., P. Aumeier and B. Ziegelmann. 2010. Biology and control of Varroa destructor. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103: S96-S119.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2009.07.016]

-

Roth, M. A., J. M. Wilson, K. R. Tignor and A. D. Gross. 2020. Biology and management of Varroa destructor (Mesostigmata: Varroidae) in Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) colonies. J. Integr. Pest. Manag. 11(1): 1.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/jipm/pmz036]

-

Sammataro, D., P. Untalan, F. Guerrero and J. Finley. 2005. The resistance of varroa mites (Acari: Varroidae) to acaricides and the presence of esterase. Int. J. Acarol. 31(1): 67-74.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/01647950508684419]

-

Smith, K. M., E. H. Loh, M. K. Rostal, C. M. Zambrana-Torrelio, L. Mendiola and P. Daszak 2013. Pathogens, pests, and economics: drivers of honey bee colony declines and losses. EcoHealth 10: 434-445.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-013-0870-2]

-

Tihelka, E. 2018. Effects of synthetic and organic acaricides onhoney bee health: a review. Slov. Vet. Res. 55(3): 114-140.

[https://doi.org/10.26873/SVR-422-2017]

-

Traynor, K. S., F. Mondet, J. R. de Miranda, M. Techer, V. Kowallik, M. A. Oddie and A. McAfee. 2020. Varroa destructor: A complex parasite, crippling honey bees worldwide. Trends. Parasitol. 36(7): 592606.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2020.04.004]

- Underwood, R. M. and R. W. Currie. 2003. The effects of temperature and dose of formic acid on treatment efficacy against Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae), a parasite of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Exp. Appl. Acarol. 29: 303-313.

- VanEngelsdorp, D., R. Underwood, D. Caron and J. Hayes, Jr, 2007. An estimate of managed colony losses in the winter of 2006-2007: a report commissioned by the Apiary Inspectors of America. Am. Bee. J. 147: 599- 603.

-

Warrit, N. and C. Lekprayoon. 2010. Asian honeybee mites. In Honeybees of Asia (pp. 347-368). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16422-4_16]

- Wilde, J., J. Woyke, K. R. Neupane and M. Wilde. 2000. Comparative evaluation tests of different methods to control Tropilaelaps clareae, a mite parasite in Nepal. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Tropical Bees and 5th AAA Conference.

- Wongsiri, S., P. Tangkanasing and S. Vongsamanode. 1989. Effectiveness of Asuntol (coumaphos), Perizin (coumaphos), Mitac (amitraz) and powder of sulphur with naphthalene for the control of bee mites (Varroa jacobsoni and Tropilaelaps clareae) in Thailand. Proceedings of the XXXIst International Congress of Apiculture, Warsaw, Poland, August 19-25, 1987: 322-325.

- Woo, K. S. and J. H. Lee. 1993. The Study on The Mites In-habiting the Bee-Hives in Korea I. J. Apic. 8(2): 140- 156.

- Woo, K. S., K. S. Cho and Y. S. Lew. 1994. Analysis on the Level of Damages Caused by Honeybee MItes. J. Apic. 9(1): 33-39.

-

Woyke, J. J. J. O. A. R. 1987. Length of successive stages in the development of the mite Tropilaelaps clareae in relation to honeybee brood age. J. Apic. Res. 26(2): 110- 114.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.1987.11100746]