국내 자생하는 환경부 지정 적색목록 호랑가시나무 (Ilex cornuta)의 꽃에 대한 재래꿀벌 (Apis cerana)과 양봉꿀벌 (Apis mellifera)의 선호도 비교

Abstract

Bees rely on color and scents to locate blooming flowers. Flowering plants actively emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and eliciting behavioral responses in bees. Horned holly (Ilex cornuta) is evergreen shrub attracting pollinators with its dioecy flower blooming from April to May. Based on the observation that the horned holly blossom was more visited by Apis cerana and apple blossom nearby was more visited by A. mellifera. We hypothesized that the native honey bee is more closely associated with the native horned holly flower than the alien species of honeybee. Laboratory assessment evaluated the preference of each pollinator (A. cerana and A. mellifera to horned holly and apple using Y-Tube Olfactometer in choice and no-choice tests. Subsequently, VOCs from I. cornuta flower were analyzed using GC-MS. In no-choice Y-Tube tests, both A. cerana and A. mellifera exhibited a stronger preference for the horned holly compared to the control. In choice test, A. mellifera did not show different preference, but A. cerana showed significant preference to the horned holly over apple. Analysis of VOCs of I. cornuta revealed that 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, 3-Methylpentanol, (Z)-3-Hexenol, Methyl Alcohol and (E)-2-Hexenal were the major components. As the horned holly has limited distribution and is register in the red list, pollination by A. cerana can be important component for the conservation program.

Keywords:

Choice, No-choice, Apple, Conservation, Pollination서 론

호랑가시나무 (Ilex cornuta)는 감탕나무과 (Aquifolia-ceae) 감탕나무속 (Ilex)에 속하는 상록활엽 소교목으로 우리나라 전라남도와 전라북도 해안가와 제주도에 제한적으로 자생지가 분포하고 있다 (Son et al., 2007). 호랑가시나무의 꽃은 4~5월에 암수딴그루로 총생하며, 꽃대의 꼭대기 끝에 5~6개의 꽃이 방사형으로 달린 산형꽃차례 (Umbel)의 형태를 가진다. 수꽃의 경우 지름 약 7 mm로 하얀색을 띤다. 또한, 호랑가시나무는 세계자연보전연맹 (International Union for Conservation of Nature)에 적색목록 관심대상 (Least Concern, LC)에 등재되어 있으며 (환경부 국립생물자원관), 종 보존을 위한 화분매개자의 역할이 매우 중요하다.

화분매개자는 전체 작물의 75%를 포함해 전 세계 개화 식물의 80% 이상의 번식을 돕는다 (Klein et al., 2007; Potts et al., 2016). 그중 꿀벌상과의 벌 (Hymenoptera, Apoidea)은 가장 중요한 화분매개자로 간주되는데, 이들은 전 세계적으로 약 20,000종이 있을 정도로 다양성이 높다 (Michener, 2007). 곤충과 현화식물의 공존은 1억 2천만 년 전인 백악기 초기에 처음 시작되었으며, 이러한 공존은 식물이 꽃꿀이나 꽃가루 등 곤충에게 먹이자원을 제공하고 곤충은 꽃가루를 옮겨주어 식물의 번식을 돕는 상호 관계로 이어졌다 (Engel, 2000; Poinar and Danforth, 2006; Bascompte, 2019).

화분매개자 중 특히 꿀벌은 꽃의 특징 (향기, 색, 모양, 질감 및 기타 꽃의 신호)과 보상 (꽃꿀과 꽃가루) 사이의 연관성을 학습하고 이를 효과적으로 사용하여 개화 중인 식물을 찾는다 (Whitney et al., 2009; Clarke et al., 2013; Muth et al., 2016). 이러한 꽃 신호의 상대적 중요성은 화분매개 시스템에 따라 다르다. 현재까지 화분매개 생물학은 색, 모양, 크기를 포함하여 화분매개자를 유인하는 것에 대해 시각적 단서에 초점을 맞춰왔으며 (Raguso, 2008), 이러한 특성은 식물-화분매개자 상호작용 네트워크에서 연결 패턴에 기여하는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Vázquez et al., 2009). 후각 신호는 화분매개자가 쉽게 학습하고 기억하기 때문에 꿀벌이 꽃을 재방문하는 데 중요하게 작용하며 (Wright and Schiestl, 2009), 멀리서 숙주 식물의 위치를 찾는 등 시각적 신호가 제한적일 때도 후각 신호는 중요하게 작용한다 (Raguso and Willis, 2002; Raguso et al., 2003). 식물이 방출하는 휘발성 물질이 식물과 동물 사이의 의사소통을 원활하게 한다는 개념은 오랫동안 연구되어왔다 (Fraenkel, 1959). 꽃 피는 식물은 휘발성 유기 화합물 (VOCs)을 방출하고 꿀벌의 행동반응을 이끌어 내는 것으로 잘 알려져 있으며 (Williams, 1983; Knudsen et al., 2006), 꽃향기는 수백 개의 다양하고 복잡한 휘발성 분자로 구성된다 (Bisrat and Jung, 2022). 식물의 VOCs는 꿀벌, 뒤영벌, 꼬마꿀벌 (Stingless bee)에서 내역벌과 외역벌 사이의 상호작용, 의사소통 및 집합에도 영향을 미치는 것으로 알려져 있다 (Ribbands, 1954; Lindauer and Kerr, 1960; Johnson, 1967; Free, 1969; Koltermann, 1969; Wenner et al., 1969; Getz and Smith, 1987; Jakobsen et al., 1995; Dornhaus and Chittka, 1999; Reinhard et al., 2004; Arenas et al., 2007; Díaz et al., 2007; Arenas et al., 2008; Molet et al., 2009). 각 벌 무리는 서로 다른 식물의 꽃꿀과 꽃가루를 소비하며 서로 다른 향기를 획득하여 무리 특유의 꽃 향기 패턴이 발달하게 된다 (Cardé et al., 1995). 식물-화분매개자 상호작용에서 화학적 의사소통의 역할을 고려할 때 꽃향기의 VOCs를 이해하고 식별하는 것은 식물과 화분매개의 상호작용을 이해하는 데 매우 중요한 데이터가 될 수 있다 (Dekebo et al., 2022).

본 연구에서는 호랑가시나무 (I. cornuta)와 사과나무 (Malus domestica) 꽃에 재래꿀벌 (Apis cerana)과 양봉꿀벌 (Apis mellifera)이 선택적으로 방문하는 것을 관찰한 후, 식물이 방출하는 VOCs를 대상으로 각 꿀벌 종의 선호성을 검정하였다. 또한 향기분석을 실시하여 호랑가시나무 꽃에서 발생하는 향기물질과 사과나무 꽃의 향기 물질을 비교하였다. 이를 통해 토착종인 호랑가시나무에는 재래꿀벌이, 도입 식물인 사과나무에는 도입종인 양봉꿀벌이 선호된다는 가설을 검정하고자 하였다. 야외 화분매개곤충상 조사 결과 각 꿀벌 종은 호랑가시나무와 사과나무를 선택적으로 방문하였으며, Y 자관 실험 결과 각 꿀벌은 호랑가시나무 꽃을 먹이자원으로서 인식하였다. 특히 재래꿀벌은 호랑가시나무 꽃을 더 선호하는 경향을 보였으며, 양봉꿀벌의 경우에는 선호성을 보이지 않았다. 향기분석 결과 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, 3-Methylpentanol, (Z)-3-Hexenol, Methyl Alcohol, (E)-2-Hexenal과 같은 향기물질이 선호성에 영향을 줄 수 있는 것으로 조사되었다. 향후 검출된 향기 물질에 대한 구체적인 분석과 이외에도 호랑가시나무 꽃의 시각적, 형태적 구조에 대한 추가적인 연구를 통해 재래꿀벌과 호랑가시나무에 대한 연관성을 파악하고자 한다.

재료 및 방법

1. 실험 지역 및 실험 재료 채집

실험은 야외 화분매개곤충상 조사, Y 자관을 이용한 실내 호랑가시나무 꽃의 선호도 실험, 호랑가시나무 꽃의 향기분석을 진행하였으며, 2023년 4월부터 2023년 5월까지 수행되었다. Y 자관 실험과 향기분석에 사용된 호랑가시나무의 꽃은 전라북도 김제시 백구면 농식품인력개발원 정원수로 식재된 나무에서 수꽃을 채집하여 사용하였다. 사과나무의 꽃을 대조구로서 Y 자관 실험에 사용하였으며, 경상북도 안동시 길안면에 위치한 과수원에서 채집하였다. 선호성 실험에 사용된 꿀벌은 재래꿀벌 및 양봉꿀벌로, 경상북도 안동시 송천동 안동대학교 부속 실험 양봉장 (36°32ʹ38ʺN, 128°48ʹ03ʺE)에서 사육 중인 봉군에서 외역활동을 나오는 벌을 포충망을 이용하여 채집하였다. 이후 곤충 사육통 (지름 9 cm, 높이 8 cm)에 꿀벌 20마리를 한 집단으로 구성하여 온도 33°C, 습도 65%가 유지되는 암조건의 인큐베이터에서 사육하였으며, 실험 1시간 전까지 신선한 자당 용액 (50% w/w)을 1.5 mL 미소관에 충분한 양을 제공하여 사육하였다.

2. 화분매개곤충상 조사

2023년 4월 12일 오전 9시에서 12시 사이에 전라북도 김제시 백구면 농식품인력개발원 (35°52ʹ29ʺN, 126°59ʹ08ʺE) 에 정원수로 식재되어 있는 호랑가시나무와 근처에 심겨져 있는 사과나무에서 화분매개곤충상 조사를 수행하였다. 각 관찰 시 1분씩 꽃에 방문하는 곤충을 육안으로 조사하여 기록하였으며, 이를 나무당 3회 반복하였다.

3. Y 자관 선호도 실험

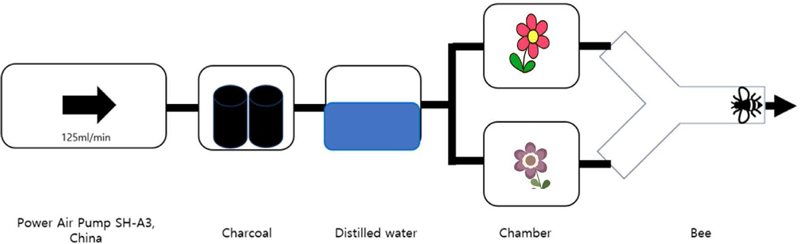

Y 자관 실험 장치의 경우 에어펌프 (Power Air Pump SH-A3, China)를 이용해 125 mL/min의 속도를 유지하여 공기를 공급하였다. 숯과 증류수로 여과시켜 두개로 나누어진 각 챔버에 동일한 양의 여과된 공기가 흐르게 하였다. 이후 Y 형태의 유리관에 공기가 통과하도록 장치를 배치하였으며, 유리관의 끝에 꿀벌을 놔두어 2개의 챔버 중 한 쪽의 챔버로 이동하는 모습을 관측하고 기록하였다. 꿀벌들에 대한 먹이 선택압이 높은 상태에서 실험하기 위해 실험 1시간 전 먹이급여를 중단하였으며, 암실조건에서 적색 등을 이용해 빛을 비추었고, 챔버 내부 온도가 25°C가 유지되는 환경에서 실험을 진행하였다.

A: blossom of apple (M. domestica), B: introduced honey bee (A. mellifera) visiting apple flower, C: Horned holly (I. cornuta) flower, D: native honey bee (A. cerana) visiting Horned holly flower.

Schematic design of Y-tube olfactometer used to determine the honey bee preference to the flower odor sources.

실험은 비선택조건 (no-choice experiment)과 선택조건 (choice experiment)으로 구성하였다. 비선택조건은 호랑가시나무 꽃 처리구와 무처리구를 두어, 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌이 호랑가시나무 꽃을 먹이원으로 인지하는지를 확인하였다. 선택조건은 비슷한 개화 정도를 보이는 호랑가시나무 꽃과 사과나무 꽃을 두고 꿀벌의 선택 선호도를 조사하였다. 각 실험은 9반복으로 진행하였으며, 반복당 10마리의 벌을 사용했다. 실험에 사용된 꿀벌은 모두 외역 활동을 위해 출소하는 벌을 채집하여 사용하였기에 발육단계가 비슷한 것들이다.

곤충용 핀셋을 사용하여 사육 케이지에서 꺼내 Y 형태의 유리관의 시작 부분에 배치한 후 입구를 공기가 통할 수 있도록 구멍이 있는 실리콘 마개를 사용하여 닫았다. 실험은 Hang et al. (2020)의 방식에 따라 진행되었다. 한 번에 5분 동안 관측하였으며, 양쪽 챔버 중 한쪽을 향해 이동하여 10초 이상 머물러 있는 것을 선택의 기준으로 판단하였다. 5분 동안 선택하지 못하고 가만히 있거나, 양쪽 챔버에 머물러 있지 못하고, 계속 이동하는 꿀벌은 제거하고 선택을 하지 않는 것으로 판단하였다. 각 반복당 꿀벌은 단 한 번만 사용하였고, 처리구 및 대조구의 향기의 잔향으로 인한 실험의 오류를 줄이기 위해 반복마다 Y 형태의 유리관을 세척하여 다시 사용하였으며, 유리관 교체 시 챔버와 연결되는 부분의 방향을 매번 바꾸어 실험을 진행하였다.

4. 향기 분석

먼저 전처리 단계로 호랑가시나무의 꽃을 줄기와 잎부분을 최대한 제거하여, 꽃 부분만 남도록 한 후 균질화를 위해 액체질소에 동결시킨 후 막자사발에서 분쇄하였다. 이후 분쇄한 꽃 시료 1 g을 GC-MS (Agilent 8890 GC/Agilent 5977B MSD, Santa Clara, CA, United States)를 이용하여 향기 분석을 진행하였으며, 내부표준품으로서 Cyclohexanone을 2500 ppm으로 5μL 주입하였다. GC 분석은 선행 연구에서의 조건으로 분석하였다 (Farag et al., 2015). 이후 결과는 각 성분의 피크 면적을 총 피크 면적으로 나누어 계산하였다.

5. 자료 분석

화분매개곤충상 조사에서 호랑가시나무와 사과나무에 방문하는 곤충상의 결과는 t-test를 이용해 검정하였다. Y 자관 실험에서 호랑가시나무의 꽃에 대한 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌의 선호도를 비교하여 얻어진 데이터는 카이제곱검정으로 분석하였다.

결 과

1. 화분매개곤충상 조사

화분매개곤충상 조사 결과 호랑가시나무와 사과나무에서 총 2목, 3과, 5속, 6종의 곤충이 관찰되었다. 호랑가시나무 꽃에는 모든 반복에서 양봉꿀벌보다 재래꿀벌의 방문 비율이 높았으며, 사과 꽃에는 양봉꿀벌의 방문 비율이 높았다 (Table 2).

2. 실내 조건에서의 꿀벌의 식물별 선호도

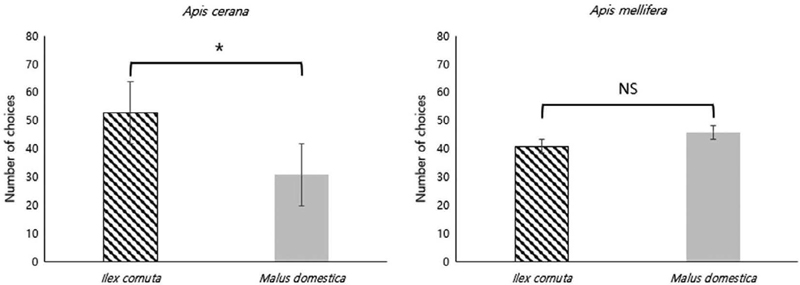

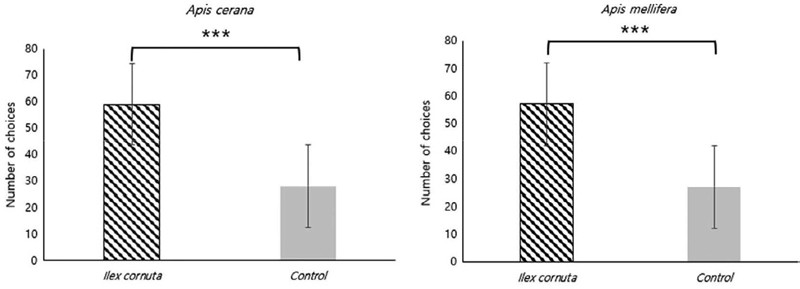

Y 자관 선호성 실험 결과 호랑가시나무와 무처리구를 비교한 비선택조건 실험에서는 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌 모두 무처리에 비해 호랑가시나무의 꽃을 선호하였으며, 통계적으로도 유의미하였다 (A. cerana: X2=10.714, p=0.001 A. mellifera: X2=11.046, p=0.0008) (Fig. 3).

Preference of the horned holly flowers (I. cornuta) in no-choice test by two species of honey bees, A. cerana and A. mellifera. Both species showed statistically significant difference (A. cerana: X2=10.714, p=0.0001; A. mellifera: X2=11.043, p=0.0008). The error bar indicates standard deviation.

재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌이 비슷한 개화시기를 가지는 호랑가시나무의 꽃과 사과나무의 꽃 중 어떤 꽃을 더 선호하는지 파악하기 위해 진행한 선택조건 실험에서는 재래꿀벌의 선호성의 경우 사과나무에 비해 호랑가시나무를 더 선호하는 경향을 보였으며, 통계적으로 유의미한 차이가 있었다 (A. cerana: X2=5.7619, p=0.0164). 양봉꿀벌의 선호성의 경우 호랑가시나무와 사과나무 사이의 통계적 차이는 나타나지 않았다 (A. mellifera: X2=0.28736, p=0.5919) (Fig. 4).

3. 향기 분석

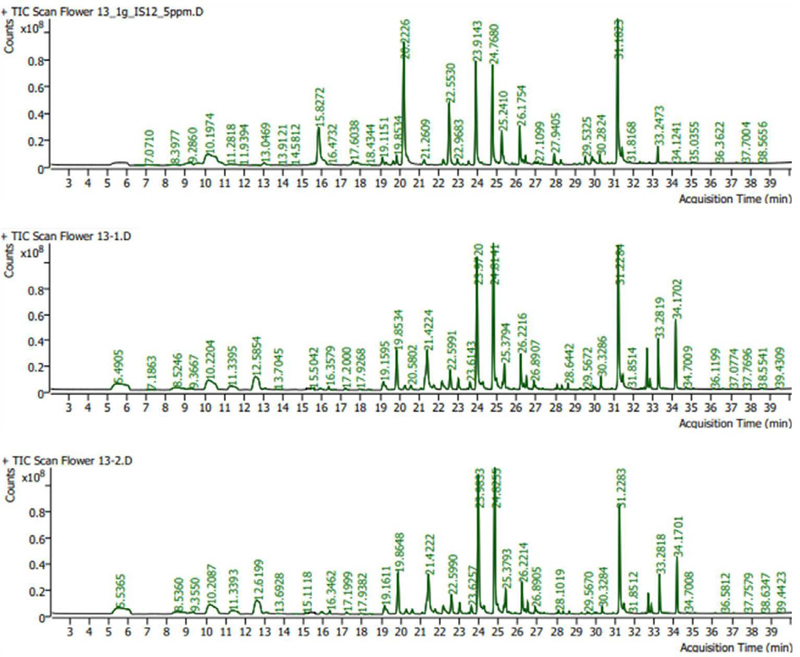

호랑가시나무의 향기 분석 결과 23분, 24분, 31분에서 가장 높은 피크가 검출되었으며, 70종의 휘발성 물질이 검출되었다. 총 목록은 Appendix 1에 제시하였고, 그중 0.5% 이상 상대빈도가 높은 화학물질은 Table 3에 제시하였다. 이 중 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, 3-Methylpentanol, (Z)-3-Hexenol, Methyl Alcohol, (E)-2-Hexenal이 높은 비율로 확인되었다 (Fig. 5, Table 3).

고 찰

방화곤충들은 식물이 생성하는 향기를 통해 꽃의 위치를 파악하고 먹이활동을 한다 (Whitney et al., 2009; Dekebo et al., 2022). 본 연구에서도 비선택조건에서 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌은 무처리에 비해 처리구인 호랑가시나무와 사과의 꽃을 선택하여 그쪽으로 향하는 행동을 보여 주었다. 반면 선택조건 실험에서, 호랑가시나무와 사과의 꽃을 동시에 제공했을 때, 재래꿀벌은 호랑가시나무에 더 높은 선호성을 보였으나, 양봉꿀벌은 비슷한 정도로 선호성을 보여, 두 종의 선호성에서 차이가 있음을 확인하였다.

꿀벌들은 향기에 대한 보상을 통해 며칠에서 평생 동안 학습과 기억을 한다 (Hammer and Menzel, 1995)는 선행 연구가 있다. 이는 꿀벌의 학습 및 기억과 같은 경험적인 부분 또한 식물에 대한 선호성에 영향을 미칠 수 있다고 말한다. 본 논문의 야외 화분매개곤충상 조사에서 양봉꿀벌의 경우 호랑가시나무 꽃에 비해 사과나무 꽃에 방문하는 비율이 더 높았지만, Y 자관 실험 결과에서는 선호도에서 두 식물 간의 차이가 보이지 않았다. 이는 Y 자관 실험에 사용한 양봉꿀벌은 오랜 기간 동안 호랑가시나무가 없는 환경의 안동대학교 부속 양봉장에서 사육되어 왔으며, 실험 이전에 호랑가시나무의 꽃에 노출된 경험이 없었기에, 꽃 관련 향기는 물론 색, 형태, 크기 및 보상에 대한 학습과 기억을 통한 행동 조정이 이루어지지 않았을 가능성이 높다. 그러나 야외 화분매개곤충상 조사에서는 향기뿐 아니라 꽃의 색, 형태, 크기 등 꽃의 특성과 보상 요인인 꽃꿀과 꽃가루 등을 통한 학습과 기억에 따른 행동 조정이 이루어졌기에 같은 지역에 존재하는 호랑가시나무 꽃과 사과 꽃에 차별적 선호성을 보였다고 본다.

실험과정에서 초기 반복과 후기 반복에서 통계적으로 유의미하지는 않지만 선호성의 양상이 조금 다르게 나타남이 일부 관찰되었다. 이는 실험 전 꿀벌의 절식시간이 1시간으로는 충분하지 않았기 때문으로 판단된다. 꿀벌 섭식 독성 실험에서 꿀벌의 효율적인 절식기간은 50%의 자당용액을 급여한 꿀벌의 경우, 실험 2시간 전 절식을 하는 것이 가장 효율적이라는 결과가 있다 (Fournier et al., 2014). 또한 실험을 진행하는 데 시간이 많이 걸릴 경우, 꿀벌의 피로도가 증가하여 선호성이 뚜렷해지지 않을 수도 있다.

호랑가시나무 꽃의 향기 분석 결과 70종의 향기 성분이 검출되었으며, 강렬하고 달콤한 꽃향기인 1,4-Dime-thoxybenzene, 매운 고추 향기인 3-Methylpen tanol, 풀잎 녹색 냄새인 (Z)-3-Hexenol, 과일향의 (E)-2-Hexenal 등이 주를 이루었다. 반면, 사과의 여러 품종과 꽃사과의 꽃을 분석한 Fan et al. (2018)의 연구에서, M. ‘Brandywine’에서는 5-methyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one이 23.8%, M. ‘Van Eseltine’에서는 5-methyl-1,3-dihydro-2H-benzimidazol-2-one, linalool과 benzyl alcohol이 전체 함량의 50.1%를 차지하였다. 또한, M. sylvestris에서는 benzyl alcohol, α-cedrene, 4-pyrrolidinopyridine이 전체 함량의 46.3%를 구성하였으며, M. ‘Hillieri’에서는 benzyl alcohol과 α-cedrene이 전체 함량의 51.7%를 차지한다고 보고하였다 (Appendix 2). 두 식물이 방출하는 향기 물질은 매우 다른 양상을 보이고 있다. 여러 꿀벌 군집은 서로 다른 꽃에서 발생하는 밀원을 채집하며 서로 다른 향기를 획득하여 군집 특유의 선호하는 꽃 향기 패턴이 존재한다 (Cardé et al., 1995; Bisrat and Jung, 2022; Dekebo et al., 2022). 이후 추가적인 분석을 진행하여 사과나무 꽃과 호랑가시나무 꽃의 어떤 특정 향기 물질이 재래꿀벌에 대한 선호도가 증가하는지 검출된 향기 물질의 분석이 필요하다.

꿀벌은 후각 신호가 가장 중요하지만, 시각적인 요소 (꽃의 형태, 크기, 색)도 중요하게 작용하며, 꽃은 두 가지 형태의 신호를 조합하여 더욱 효율적으로 곤충을 유인한다 (Raguso and Willis, 2002; Burger et al., 2010; Milet-Pinheiro et al., 2012). 호랑가시나무 꽃과 사과나무 꽃은 비슷한 개화시기를 가지며, 동일한 하얀색의 꽃이 피며, 산형꽃차례로 동일한 화서를 가진다. 하지만 호랑가시나무 꽃의 경우 사과나무 꽃과는 달리 화관이 작은 크기의 꽃을 가지며, 밀선까지의 깊이 또한 매우 얕다. 화관의 깊이와 호박벌의 혀의 길이 사이의 상관관계에 대한 선행 연구 (Peat et al., 2005)에 따르면, 큰 몸체를 가지는 벌은 작은 몸체를 가지는 벌과 비교했을 때, 보다 깊은 화관을 가지는 꽃을 선호하는 경향이 있다. 이는 깊은 화관을 가지는 식물의 경우 큰 몸체를 가지는 벌은 작은 몸체를 가진 벌에 비해 꽃꿀을 채집하는 시간이 더 오래 걸리기 때문이다. 선행 연구 결과 양봉꿀벌의 혀의 길이는 6.49±0.063인 것에 비해 재래꿀벌의 혀의 길이는 5.33±0.044로 상대적으로 짧은 혀의 길이를 가지며 (Lee and Choi, 1986), 비교적 작고 얕은 화관을 가지는 호랑가시나무 꽃의 경우에는 재래꿀벌이 보다 효율적으로 채집 활동을 할 수 있다.

또한, 호랑가시나무와 재래꿀벌은 대한민국 자생종으로서 오랜 시간 동안 공진화 과정을 통해 상생적 관계를 이루어 온 생물로 판단된다. 양봉꿀벌은 1900년대 초에 도입된 생물로 (Jung, 2014) 호랑가시나무와의 공존이 비교적 짧은 편이며, 더 긴 공진화 과정을 거친 재래꿀벌이 호랑가시나무 꽃에서 방출되는 후각적, 시각적 신호와 그에 대한 보상으로 인해 높은 선호도에 영향을 미칠 가능성도 존재한다.

적 요

본 연구는 호랑가시나무와 사과나무의 꽃에 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌이 선택적으로 방문하는 것을 관찰한 후, 실내 조건에서 식물이 방출하는 후각 신호를 대상으로 각 꿀벌 종의 선호성을 Y 자관 실험을 통해 검정하였다. 비선택 조건에서 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌는 모두 호랑가시나무 꽃의 향기에 이끌려 선택하는 양상을 보였다. 그러나 선택조건에서 재래꿀벌은 비슷한 개화시기를 가지는 사과나무 꽃에 비해 호랑가시나무 꽃을 더 선호하는 경향이 확인되었다. 호랑가시나무의 꽃의 향기 분석 결과 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene, 3-Methylpentanol, (Z)-3-Hexenol, Methyl Alcohol, (E)-2-Hexenal과 같은 향기 물질이 가장 넓은 피크 면적을 보여 주었다. 반면 사과나무 꽃에서는 benzyl alcohol 계열의 linalool, indole 등이 양봉꿀벌을 유인하는 것으로 보고된 바 있으나, 호랑가시나무 꽃에서는 benzyl alcohol만이 소량 존재하였다 (Rachersberger et al., 2019). 향후 검출된 향기 물질에 대한 구체적인 분석과 이외에도 호랑가시나무 꽃의 시각적, 형태적 구조에 대한 추가적인 연구를 통해 재래꿀벌과 호랑가시나무에 대한 연관성을 파악하고, 주요 화분매개 곤충인 재래꿀벌과 양봉꿀벌, 적색목록 관심종 (LC)인 호랑가시나무의 화분매개 시스템 연구는 이 식물을 보호하는 데도 기여할 것으로 본다.

Acknowledgments

본 연구는 한국연구재단 중점연구소 지원사업 (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024862)과 농촌진흥청 연구과제인 ‘화분매개 네트워크 연구 (RS-2023-00232847)’의 지원으로 수행되었습니다.

References

-

Arenas, A., V. M. Fernández and W. M. Farina. 2007. Floral odor learning within the hive affects honeybees’ foraging decisions. Naturswiss 94: 218-222.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-006-0176-0]

-

Arenas, A., V. M. Fernández and W. M. Farina. 2008. Floral scents experienced within the colony affect long-term foraging preferences in honeybees. Apidologia 39(6): 714-722.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2008053]

-

Bascompte, J. 2019. Mutualism and biodiversity. Curr. Biol. 29(11): R467-R470.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.03.062]

-

Bisrat, D. and C. Jung. 2022. Roles of flower scent in bee-flower mediations: a review. J. Ecol. Environ. 46(1): 18-30.

[https://doi.org/10.5141/jee.21.00075]

-

Burger, H., S. Dötterl and M. Ayasse. 2010. Host-plant finding and recognition by visual and olfactory floral cues in an oligolectic bee. Funct. Ecol. 24(6): 1234-1240.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2010.01744.x]

-

Cardé, R. T., W. J. Bell, B. H. Smith and M. D. Breed. 1995. The chemical basis for nestmate recognition and mate discrimination in social insects. Chem. Ecol. Insects. 2: 287-317.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-1765-8_8]

-

Clarke, D., H. Whitney, G. Sutton and D. Robert. 2013. Detection and learning of floral electric fields by bumblebees. Science 340(6128): 66-69.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1230883]

-

Dekebo, A., M. J. Kim, M. Son and C. Jung. 2022. Comparative analysis of volatile organic compounds from flowers attractive to honey bees and bumblebees. J. Ecol. Environ. 46(1): 62-75.

[https://doi.org/10.5141/jee.21.001]

-

Díaz, P. C., C. Grüter and W. M. Farina. 2007. Floral scents affect the distribution of hive bees around dancers. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61: 1589-1597.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-007-0391-5]

-

Dornhaus, A. and L. Chittka. 1999. Evolutionary origins of bee dances. Nature 401(6748): 38-38.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/43372]

-

Engel, M. S. 2000. A new interpretation of the oldest fossil bee (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Am. Mus. Novit. 2000(3296): 1-11.

[https://doi.org/10.1206/0003-0082(2000)3296<0001:ANIOTO>2.0.CO;2]

-

Fan, J., W. Zhang, T. Zhou, D. Zhang, D. Zhang, L. Zhang, G. Wang and F. Cao. 2018. Discrimination of Malus taxa with different scent intensities using electronic nose and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Sensors 18(10): 3429.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/s18103429]

-

Farag, M. A., D. M. Rasheed and I. M. Kamal. 2015. Volatiles and primary metabolites profiling in two Hibiscus sabdariffa (roselle) cultivars via headspace SPME-GC- MS and chemometrics. Food Res. Int. 78: 327-335.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.09.024]

-

Fournier, A., O. Rollin, V. Le Féon, A. Decourtye and M. Henry. 2014. Crop-emptying rate and the design of pesticide risk assessment schemes in the honey bee and wild bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 107(1): 38-46.

[https://doi.org/10.1603/EC13087]

-

Fraenkel, G. S. 1959. The Raison d̓Etre of Secondary Plant Substances: These odd chemicals arose as a means of protecting plants from insects and now guide insects to food. Science 129(3361): 1466-1470.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.129.3361.1466]

-

Free, J. B. 1969. Influence of the odour of a honeybee colony̓s food stores on the behaviour of its foragers. Nature, 222(5195): 778-778.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/222778a0]

-

Getz, W. M. and K. B. Smith. 1987. Olfactory sensitivity and discrimination of mixtures in the honeybee Apis mellifera. J. Comp. Physiol. A. 160(2): 239-245.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00609729]

-

Hang, H., S. Shan, S. Gu, X. Huang, Z. Li, A. Khashaveh and Y. Zhang. 2020. Prior experience with food reward influences the behavioral responses of the honeybee Apis mellifera and the bumblebee Bombus lantschouensis to tomato floral scent. Insects 11(12): 884.

[https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11120884]

-

Hammer, M. and R. Menzel. 1995. Learning and memory in the honeybee. J. Neurosci. 15(3): 1617-1630.

[https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01617.1995]

-

Jakobsen, H. B., K. Kristjansson, B. Rohde, M. Terkildsen and C. E. Olsen. 1995. Can social bees be influenced to choose a specific feeding station by adding the scent of the station to the hive air?. J. Chem. Ecol. 21: 1635- 1648.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02033666]

-

Johnson, D. L. 1967. Communication among honey bees with field experience. Anim. Behav. 15(4): 487-492.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-3472(67)90048-6]

- Jung, C. 2014. A note on the Early Publication of Beekeeping of Western Honeybee, Apis mellifera in Korea: Yangbong Yoji (Abriss Bienenzucht) by P. Canisius Kugelgen: Yangbong Yoji (Abriss Bienenzucht) by P. Canisius Kugelgen. J. Apic. 29(1): 73-77.

-

Klein, A. M., B. E. Vaissière, J. H. Cane, I. Steffan-Dewenter, S. A. Cunningham, C. Kremen and T. Tscharntke. 2007. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. R. Soc. B. 274(1608): 303-313.

[https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3721]

-

Koltermann, R. 1969. New data on processes of learning and forgetting, gained from scent training of honey-bees. Z. Vergl. Physiol. 63(3): 310-334.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00298165]

-

Knudsen, J. T., R. Eriksson, J. Gershenzon and B. Ståhl. 2006. Diversity and distribution of floral scent. The Botanical Review, 72(1): 1-120.

[https://doi.org/10.1663/0006-8101(2006)72[1:DADOFS]2.0.CO;2]

- Lee, M. L. and S. Y. Choi. 1986. Biometrical studies on the variation of some morphological characters in Korean honeybees, Apis cerana F. and A. mellifera L. J. Apic. 1(1): 5-23.

-

Lindauer, M. and W. E. Kerr. 1960. Communication between the workers of stingless bees. Bee World 41(2): 29-41.

[https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.1960.11095309]

- Michener, C. D. 2007. The bees of the world. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

Milet-Pinheiro, P., M. Ayasse, C. Schlindwein, H. E. Dobson and S. Dötterl. 2012. Host location by visual and olfactory floral cues in an oligolectic bee: innate and learned behavior. Behavioral Ecology 23(3): 531-538.

[https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arr219]

-

Molet, M., L. Chittka and N. E. Raine. 2009. How floral odours are learned inside the bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) nest. Naturswiss 96: 213-219.

[https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-008-0465-x]

-

Muth, F., D. R. Papaj and A. S. Leonard. 2016. Bees remember flowers for more than one reason: pollen mediates associative learning. Anim Behav. 111: 93-100.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.09.029]

-

Peat, J., J. Tucker and D. Goulson. 2005. Does intraspecific size variation in bumblebees allow colonies to efficiently exploit different flowers? Ecological Entomology, 30(2): 176-181.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0307-6946.2005.00676.x]

-

Poinar Jr, G. O. and B. N. Danforth. 2006. A fossil bee from Early Cretaceous Burmese amber. Science 314(5799): 614-614.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134103]

-

Potts, S. G., V. Imperatriz-Fonseca, H. T. Ngo, M. A. Aizen, J. C. Biesmeijer, T. D. Breeze, L. V. Dicks, L. A. Garibaldi, R. Hill, J. Settele and A. J. Vanbergen. 2016. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature 540(7632): 220-229.

[https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20588]

-

Raguso, R. A. 2008. Start making scents: the challenge of integrating chemistry into pollination ecology. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 128(1): 196-207.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2008.00683.x]

-

Raguso, R. A., R. A. Levin, S. E. Foose, M. W. Holmberg and L. A. McDade. 2003. Fragrance chemistry, nocturnal rhythms and pollination “syndromes” in Nicotiana. Phytochemistry 63(3): 265-284.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00113-4]

-

Raguso, R. A. and M. A. Willis. 2002. Synergy between visual and olfactory cues in nectar feeding by naıve hawkmoths, Manduca sexta. Anim. Behav. 64(5): 685-695.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2002.4010]

-

Rachersberger, M., G. D. Cordeiro, I. Schäffler and S. Dötterl. 2019. Honeybee pollinators use visual and floral scent cues to find apple (Malus domestica) flowers. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67(48): 13221-13227.

[https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06446]

-

Reinhard, J., M. V. Srinivasan, D. Guez and S. W. Zhang. 2004. Floral scents induce recall of navigational and visual memories in honeybees. J. Exp. Biol. 207(25): 4371-4381.

[https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.01306]

-

Ribbands, C. R. 1954. Communication between Honeybees. I: The Response of Crop-Attached Bees to The Scent of Their Crop. Proc. R. Ent. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, Gen. Entomol. 29(10-12): 141-144.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3032.1954.tb01187.x]

-

Son, S. W., J. H. Kim, Y. S. Kim and S. J. Park. 2007. ITS sequence variations in populations of Ilex cornuta (Aquifoliaceae). KJPT 37(2): 131-141.

[https://doi.org/10.11110/kjpt.2007.37.2.131]

-

Vázquez, D. P., N. P. Chacoff and L. Cagnolo. 2009. Evaluating multiple determinants of the structure of plant-animal mutualistic networks. Ecology 90(8): 2039-2046.

[https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1837.1]

-

Wenner, A. M., P. H. Wells and D. L. Johnson. 1969. Honey bee recruitment to food sources: olfaction or language? Science 164(3875): 84-86.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.164.3875.84]

-

Whitney, H. M., M. Kolle, P. Andrew, L. Chittka, U. Steiner and B. J. Glover. 2009. Floral iridescence, produced by diffractive optics, acts as a cue for animal pollinators. Science 323(5910): 130-133.

[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1166256]

- Williams, N. H. 1983. Floral fragrances as cues in animal behavior. Handbook of Experimental Pollination Biology, 51-69.

-

Wright, G. A. and F. P. Schiestl. 2009. The evolution of floral scent: the influence of olfactory learning by insect pollinators on the honest signalling of floral rewards. Funct. Ecol. 23(5): 841-851.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01627.x]