서양뒤영벌( Bombus terrestris)의 성적 성숙시기 및 교미능력

Abstract

To secure superior traits of the Bombus terrestris through increased mating rate, we investigated the age of sexual maturity of queen and male, and mating ability of male. In the age of sexual maturity of queen, mating occurred at 6.7% immediately after eclosion and it was the highest as 85.0% at 10 days after emergence. However, a remarkable decrease was occurred at 20 days after the emergence. With regard to oviposition rate, the highest rate was observed as 81.3~81.8% at 6 to 10 days of eclosion. The rate of colony foundation and progeny-queen production were the highest as 43.8% and 37.5%, respectively, at 8 days of eclosion. In the age of sexual maturity of male, mating rate was as high as 38.3% immediately after the eclosion, the highest as 80.0% at 25 days of eclosion, and 76.6% at 8 days of eclosion. The oviposition rate was the highest as 76.9% at 6 days of eclosion, and decreased to 75.0% at 8 days and 72.7% at 10 days of eclosion. The rate of colony foundation and progeny-queen production were the highest as 40.9% and 40.9%, respectively, at 10 days of eclosion. Summarized, our results indicate that sexual maturity for mating of B. terrestris is most favorable 6~8 days after eclosion for queen and 6~10 days after for male. In terms of mating ability of male, it turned out that each B. terrestris male is able to mate up to seven times. The mating rate was 74.3% at first mating, 25.3% at second mating, 15.3% third mating, 11.7% at fourth mating, 7.0% at fifth mating, 3.3% at sixth mating and 0.3% at seventh mating. The rate of oviposition, colony foundation and progeny-queen production of the queen mated for only one time were 83.0%, 45.0% and 45.0%, respectively, presenting two-fold improvement in the colony development that of twice mating.

Keywords:

Bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, Mating, Age, Sexual maturity서 론

전 세계 작물의 75%는 화분매개자에 의존하며, 연 2,350~5,700억톤의 작물생산이 화분매개자와 직접적인 관련이 있다고 보고하였고( IPBES, 2016), 화분매개 곤충이 사라지면 1,900-3,100억 유로의 손실이 발생할 것으로 추산하였다( Galli et al., 2009 ). 화분매개자 중 벌(Bees)은 매우 다양하고 풍부해서 전 세계적으로 현재까지 16,325종이 동정되었다( Michener, 2000). 벌은 자연식생 뿐만 아니라 과일, 채소, 종자식물, 유료작물, 노지화초와 주요한 사료작물 등을 포함한 농작물의 수분을 위해 매우 중요한 역할을 한다( Morandin and Winston, 2005; Greenleaf and Kremen, 2006; Winfree et al., 2007 ). 상업적으로 관리되는 벌들도 수분작용 서비스에 이용될 뿐만 아니라 대규모의 상업용 경작지, 소규모 정원, 그리고 유리온실과 비닐하우스와 같은 곳에서 사용되고 있다( Free, 1993; Dag and Kammer, 2001).

상업적으로 판매되는 벌 가운데 뒤영벌은 북반구의 온대와 아한대에 분포 중심을 갖고 한냉, 다습한 기후에 적응해온 진사회성 곤충으로 전 세계에 약 239종이 보고되고 있다( Hannan et al., 1998 ; Williams, 1998). 유럽산 뒤영벌은 1987년 북유럽을 중심으로 시설 채소 및 과수 등의 화분매개곤충으로 상품화되어 세계 각국에 판매되기 시작하였다( de Ruijter, 1997; Free, 1993; Masahiro, 2000). 2004년, 전 세계 뒤영벌 생산량은 약 100만 상자로 추정되며 그 중에서 유럽산 Bombus terrestris 930,000봉군(93%), 북아메리카의 B. impatiens 55,000봉군(5.5%), 유럽산 B. lucorum, 동아시아의 B. ignitus, 그리고 북아메리카의 B. occidentalis 수천봉군(1.5%)으로 전 세계 239종의 뒤영벌 중에 단지 5종만이 상업적으로 판매되고 있다( Velthuis and van Doorn, 2006). 2015년 기준 전 세계 뒤영벌 생산량은 약 250만 봉군으로 추정되며, 국내에서는 약 10만 5천 봉군이 판매되었으며 이 중 89%가 자체 생산 판매되었다(Yoon, H. J. 개인자료).

뒤영벌은 꿀벌처럼 여왕벌, 일벌, 수벌로 이루어진 기본단위로 봉군을 형성한다( Free, 1993; Duchateau and Velthuis, 1988). 1년에 1세대인 뒤영벌은 가을철에 일벌, 수벌이 차례로 죽고, 교미를 끝낸 신여왕벌만이 땅속에 잠입하여 6~7개월간 휴면하여 이듬해 봄에 땅속에 산란을 하는 생활사를 가진다( Heinrich, 1979; Duchateau and Velthuis, 1988). 뒤영벌의 생활사 중에서 결정적인 시기는 교미이다. 서양뒤영벌( B. terrestris) 수벌의 혼인비행은 머리의 아래턱 샘에서 분비되는 ‘farnesol’로 밝혀진 페르몬을 적당 지점에 표시해 두고 순찰비행을 하며, 여왕벌과 표시해둔 비행길에서 만나 교미를 시도한다( Svensson, 1980; Williams 1991). 여왕벌 역시 큰턱 샘에서 분비되는 성페르몬을 방출한다( Honk et al., 1978 ; Bergstrom, 1981). Djegham et al.(1994) 은 혼인비행을 확인할 수 없는 교미상자 내에서 성별과 여왕벌의 움직임에 의한 더듬이의 감지가 성공적인 교미를 하는데 중요한 요인이라고 하였다. 서양뒤영벌의 교미에 적당한 나이, 정소관에서 정자의 양과 전달 등이 보고되었고( Röseler, 1973; Duchateau, 1985; Duchateau and Marién, 1995; Duvoisin et al., 1999 ), 나이, 성별에 따른 행동 및 정자 생산과의 관계가 밝혀졌다( Tasei et al., 1998 ). 또한 교미할 때 여왕벌의 재교미를 막기 위해서 수벌은 정자 전달 직후 여왕벌의 생식기 속에 4가지의 fatty acid와 cycloprolyproline으로 구성된 mating plug를 전달한다고 보고하였다( Baer et al., 2000 , 2001).

이에 본 연구에서는 현재 대량생산되고 있는 서양 뒤영벌의 교미효율을 높여 우량형질을 확보하기 위한 방법으로 여왕벌과 수벌의 교미에 적합한 나이와 수벌의 교미능력을 확인하고자 하였다. 따라서 여왕벌과 수벌의 나이별 교미율과 봉세발달 그리고 수벌의 교미횟수에 따른 교미율과 봉세발달 등을 조사하였다.

재료 및 방법

실험곤충 및 사육

실험곤충은 국립농업과학원 농업생물부 화분매개 곤충연구실에서 실내 계대사육한 5~7세대 서양뒤영벌( B. terrestris)을 사용하였다. 실험곤충 사육은 기본적으로 전에 보고된 방법( Yoon et al., 2004a )에 준하여 행하였다. 즉 사육환경은 온도 27±1°C, 습도 65±5% R.H., 암조건으로 하였다. 실험곤충은 산란용(10.5×14.5×6.5cm), 봉군 증식용(21.0×21.0×15.0cm) 및 숙성용 상자(24.0×27.0×18.0cm)를 이용하여 사육하였다. 산란용 상자는 여왕벌을 실내에 정착시켜 산란을 유도하기 위한 것으로 첫배의 일벌이 출현하면 봉군증식용 상자로 옮겨서 사육하였고, 일벌이 50마리 이상 출현하면 봉군발달을 위해 봉군 숙성용 상자에 옮겨서 사육하였다. 먹이로는 40%의 설탕물과 화분단자를 공급하였다. 화분단자는 양봉장에서 채취한 신선 화분을 40%의 설탕물로 혼합하여 긴 원통형 소시지 형태로 만든 다음 필요할 때마다 잘라서 난괴 가까이에 주었다. 40%의 설탕물은 부패방지를 위하여 0.2%의 sorbic acid를 첨가하였다.

교미에 의한 여왕벌 및 수벌의 성적 성숙시기 조사

교미에 의한 여왕벌의 성적 성숙시기 조사를 위해서 서양여왕벌은 우화 직후, 1일, 2일, 3일, 4일, 5일, 6일, 7일, 8일, 9일, 10일, 11일, 12일, 15일, 20일, 25일 및 30일째의 5세대 처녀여왕벌과 우화 10일된 수벌( Duchateau, 1985)을 사용하였다. 실험곤충 수는 여왕벌과 수벌의 비율은 1:3의 비율로 총 각 시험구당 총 30마리의 여왕벌과 90마리의 수벌을 사용하였다. 55×65×40cm 크기의 교미상자에 여왕벌 10마리와 수벌 30마리씩 총 3개의 교미상자를 사용하였다. 23~25°C, 65%, 2,000 lux의 교미환경( Yoon et al., 2008 )에서 오전 10시~12시까지 2시간 동안 교미율을 조사하였다. 수벌의 성적 성숙시기 조사를 위해서 수벌은 우화 직후, 1일, 2일, 3일, 4일, 5일, 6일, 7일, 8일, 10일, 12일, 15일, 20일, 25일, 30일, 35일 및 40일째의 수벌을 우화 6일된 처녀여왕벌( Duchateau, 1985)을 사용하여 교미율을 조사하였다. 실험곤충 수와 교미조건은 여왕벌의 성적 성숙시기와 동일하게 하였다.

봉세발달 조사를 위하여 우화 10일된 수벌과 교미한 우화 직후, 2일, 4일, 6일, 8일, 10일, 15일, 20일, 25일, 30일 여왕벌 및 우화 직후, 2일, 4일, 6일, 8일, 10일, 15일, 20일, 25일, 30일째의 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌을 사용하였다. 봉세발달 조사를 위하여 이 여왕벌들은 Yoon et al.(2003) 의 방법에 의해서 탄산가스 처리한 다음 사육하여, 산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군율 등을 조사하였다. 사육시작부터 40일 이내에 산란하지 못한 여왕벌은 산란율에서 제외하였다( Yoon et al., 2004b ). 봉군형성률은 일벌이 50마리 이상 출현한 봉군을 백분율로 계산하였다.

수벌의 교미횟수에 따른 교미율 및 봉세발달 조사

수벌의 교미능력을 확인하기 위하여 서양뒤영벌 7세대 여왕벌과 수벌을 이용하여 교미횟수에 따른 교미율 및 봉세발달을 조사하였다. 교미조건은 교미에 의한 여왕벌 및 수벌의 성적 성숙시기 조사와 동일하였다. 교미시간은 10~17시까지이었다. 교미횟수별 수벌의 교미율 조사는 교미용 상자(55×65×40cm)에 우화 6일째 여왕벌 30마리와 우화 10일째 수벌 30마리를 넣어 실험하였다. 총 10개의 교미상자를 이용하여 여왕벌 300마리와 수벌 300마리를 실험곤충으로 사용하였다. 1회 교미한 수벌을 대상으로 동일한 수의 우화 5일째 처녀여왕벌과 교미시켜 2회 교미율을 조사하였다. 3회, 4회, 5회, 6회 및 7회 교미도 1회 교미와 동일한 방법으로 교미횟수에 따른 수벌과 같은 수의 처녀여왕벌을 사용하였다. 즉 수벌의 공시충수는 1회 교미 300마리, 2회 76마리, 3회 46마리, 4회 35마리, 5회 21마리, 6회 10마리, 7회 1마리로 하였다. 교미한 여왕벌은 탄산가스 처리한 다음 사육하여, 산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군율 등 봉세발달을 조사하였다.

본 실험의 통계분석은 SPSS PASW 18.0 for windows 통계 패키지 프로그램( IBM Inc., 2007)을 이용하여 One-way ANOVA test와 Chi-square test로 통계 분석하였다.

결과 및 고찰

교미에 의한 여왕벌의 성적 성숙시기

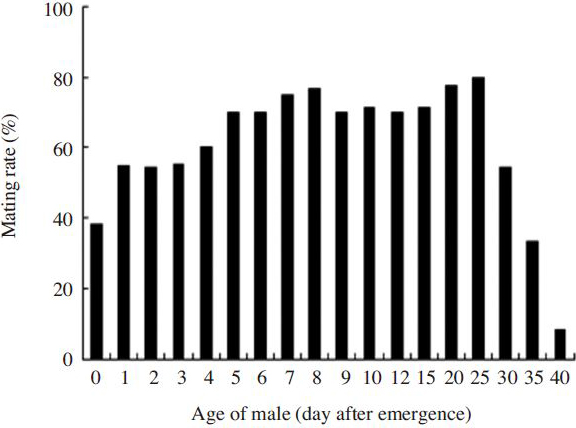

여왕벌의 성적 성숙시기를 조사하기 위해서 우화 직후부터 우화 40일째의 처녀여왕벌을 가지고 오전 10~12시까지 2시간 동안 교미율을 조사한 결과( Fig. 1), 우화직후에도 낮은 비율이기는 하지만 6.7%나 교미를 하였다. 우화 2일째에는 43.3%이었고 우화 3일째부터 6일째까지는 60.0~65.0%의 교미율을 보였다. 우화 7일부터 9일까지는 72.4~73.3%이었고 우화 10일째에는 85.0%로 가장 높았다. 그 후부터는 교미율이 떨어지는 경향을 나타내었으며, 우화 25일(34.4%)부터는 현저하게 떨어져 우화 30일째 여왕벌의 교미율은 18.9%이었다. 여왕벌의 교미율은 통계적으로 고도의 유의성이 확인되었다(Chi-square test: x 2=133.731, df=16, p=0.0001).

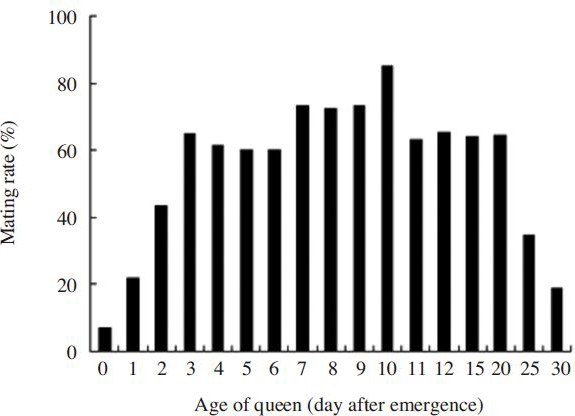

여왕벌의 교미나이에 따른 봉세발달을 조사하기 위하여, 산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군율 등을 조사하였다( Fig. 2). 산란율의 경우( Fig. 2A), 우화직후가 55.6%로 가장 낮았고, 우화 2일째는 77.8%이었다. 우화 4일부터 15일까지는 80.0~81.8%이었으나, 우화 25일(62.5%)이후로는 떨어지는 경향을 보여 우화 30일째의 산란율은 56.3%이었다. 여왕벌의 교미나이에 따른 산란율에는 통계적 유의성이 없었다(x 2=9.429, df=9, p=0.080). 봉군형성률의 경우( Fig. 2B), 우화직후가 11.1%로 가장 낮았고, 우화 8일이 43.8%로 가장 높았다. 우화 6일과 10일째 여왕벌의 봉군형성률은 각각 36.4%을 보였다. 산란율과 달리 우화 25일(26.7%) 이후에도 봉군형성률은 낮아지지 않고 우화 30일에도 31.3%를 나타내었다. 여왕벌의 나이에 따른 봉군 형성률은 통계적으로 차이가 없었다(x 2=4.258, df=9, p=0.894). Fig. 2C에서 보는 바와 같이, 신여왕출현봉군율은 우화직후와 2일이 각각 11.1%로 가장 낮았다. 우화 8일이 37.5%로 가장 높았으며, 우화 6일(36.4%) 순이었다. 우화 30일째의 신여왕출현봉군율은 25.0%로 다소 낮아지는 경향을 보였으나 통계적 유의성이 확인되지 않았다(x 2=9.429, df=9, p=0.080).

이상의 교미율과 산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군형성율 등 봉세발달로 볼 때 서양뒤영벌 여왕벌의 성적 교미나이는 우화 6일부터 우화 8일 사이로 판단된다. Tasei et al.(1998) 은 서양뒤영벌( B. terrestris) 여왕벌 90마리 중 97%가 11일 이내에 교미를 하였고, 38.8%가 7.8±0.6일째에 교미를 하여 여왕벌의 평균 교미나이는 6.1±0.4일이라고 보고하였다. 수벌은 여왕벌과 교미하여 정자전달 직후에 여왕벌의 생식기 속에 4가지의 fatty acid(palmitic, linoleic, leic, stearic acids)와 cycloprolyproline으로 구성된 mating plug를 전달한다. 4가지의 fatty acid는 끈적끈적하고 불투명한 덩어리 물리적 장벽을 만들어 수정관 전에 최대한 정자가 잘 놓여지도록 하거나 정자가 역류되는 것을 막는 기능을 한다( Baer et al., 2000 ). Sauter and Brown(2001)은 교미 전 구애행동을 위한 수벌의 잠재적인 선택에도 불구하고 실제로 교미가 될지에 대한 효과가 거의 없다. 오히려 여왕벌의 생식상태가 교미의 가장 중요한 결정요인이라고 보고하였다.

Mating rate at the age of queens. The mating rate was investigated 10:00 to 12:00 at the first day of mating periods. The mating age of male was 10 days. There was significant difference in mating rate at the age of queens at p<0.0001 using the Chi-square test.

Oviposition rate (A), rate of colony foundation (B) and rate of progeny-queen production (C) at the age of queens. There was no significant difference in colony development at the age of queens at p<0.05 using the Chi-square test.

교미에 의한 수벌의 성적 성숙시기

우화직후부터 우화 40일째까지의 수벌을 가지고 교미율에 의한 성적 성숙시기조사 결과를 Fig. 3에 나타내었다. 여왕벌과 달리 우화직후에도 38.3%의 높은 교미율을 보였으며, 우화 1~3일째는 54.3~55.3%이었다. 우화 20일이 80.0%로 가장 높았으며, 우화 25일(77.5%), 우화 8일(76.6%)순으로 낮았다. 우화 5~25일 까지는 70.0~80.0%의 교미율을 보이다가 우화 30일(54.5%)이후에는 급격하게 낮아지는 경향을 보였다. 우화 40일된 수벌도 8.3%의 교미율을 나타내었다. 교미율에 의한 수벌 성적 성숙시기는 통계적으로 고도의 유의성이 인정되었다(Chi-square test: x2=136.643, df=17, p=0.0001).

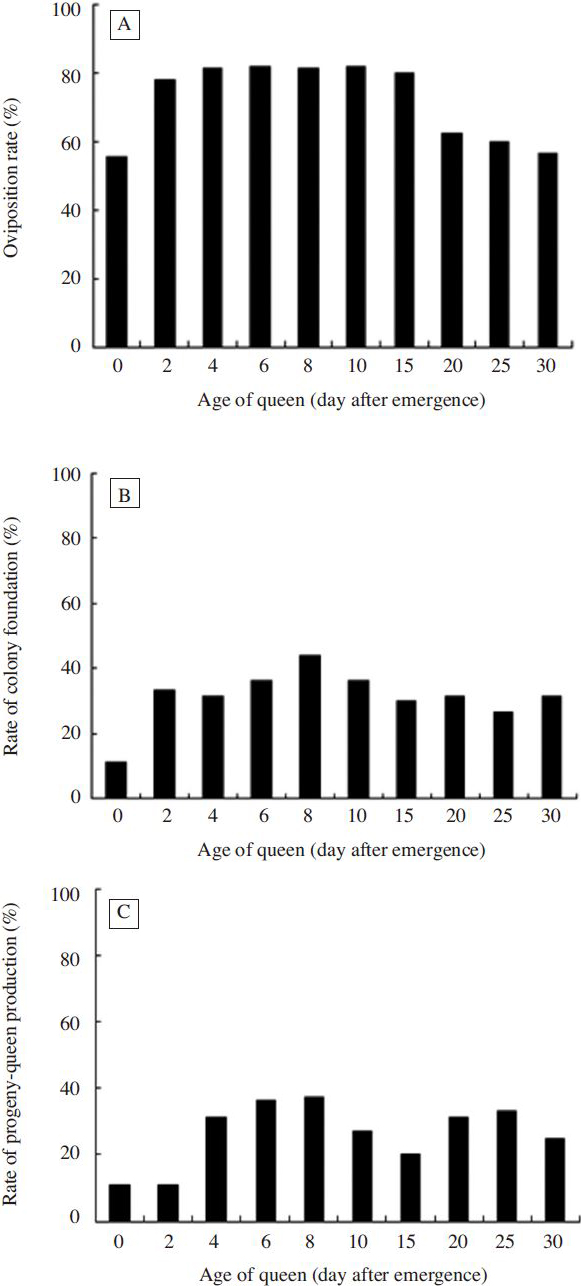

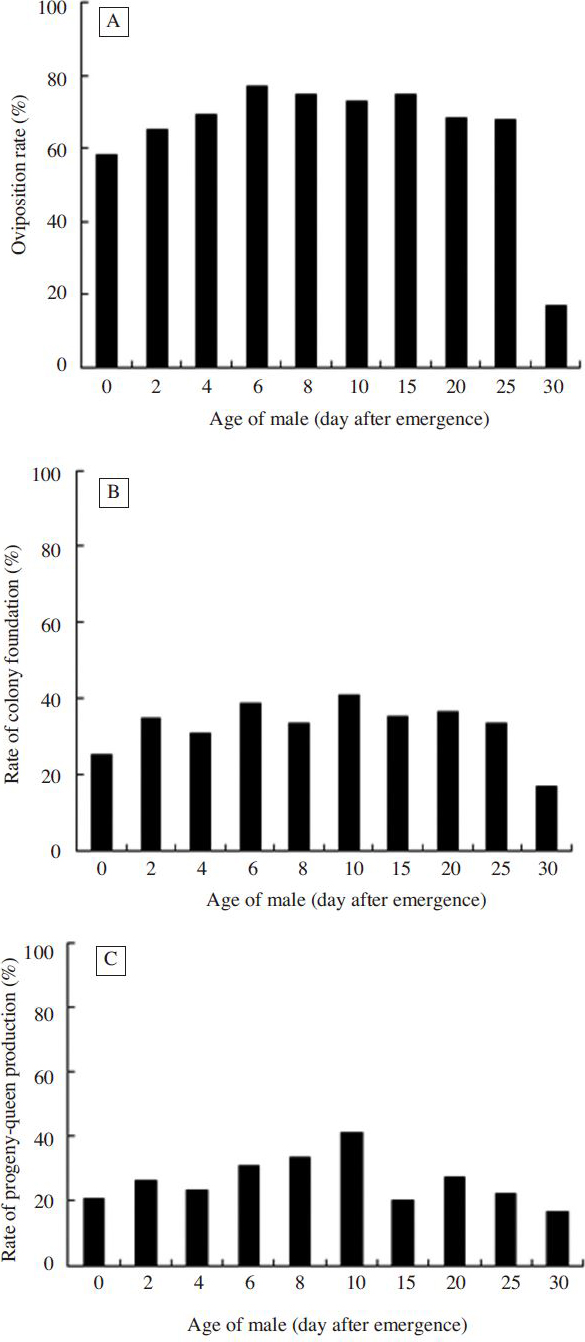

산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군율 등으로 수벌의 교미나이별 봉세발달을 조사하였다(Fig. 4). 우화 35일과 40일째 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌은 40일내에 산란하는 개체가 없어서 수벌의 교미나이별 봉세발달 조사에서 제외하였다. 우화직후부터 우화 30일까지의 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌의 산란율은(Fig. 4A), 우화 6일이 76.9%로가장높았고, 그 다음우화8일과 15일(75.0%), 우화 10일(72.7%) 순이었다. 우화직후는 58.3%이었고 우화 30일은 16.7%로 가장 낮았다. 교미 나이별 수벌의 산란율은 통계적으로 차이가 없었다. (x2=10.003, df=9, p=0.350). 봉군형성률의 경우(Fig. 4B), 우화 10일이 40.9%로 가장 높았고, 우화 2~25일은 30.8~38.5%이었다. 우화직후는 25.0%인데 반하여 우화 30일은 16.7%로 가장 낮았다. 수벌 나이별 봉군형성률 역시 통계적으로 유의성이 없었다(x2=2.260, df=9, p=0.987). 신여왕출현봉군율 또한 봉군형성률과 같이 우화 10일이 40.9%로 가장 높았다. 그 다음은 우화 8일(33.3%), 우화 6일(30.8%) 순이었다. 우화 30일이 16.7%로 가장 낮았으나, 유의성이 확인되지 않았다(x2=4.488, df=9, p=0.876).

이상의 결과로 볼 때, 서양뒤영벌 수벌은 여왕벌과 달리 우화직후부터 우화 40일까지 교미가 가능한 것으로 나타났다. 교미율과 봉세발달 등의 결과를 고려할 때, 수벌의 성적 교미나이는 우화 6일부터 우화 20일 사이로 생각되지만 최적 교미시기는 우화 6일에서 10일로 판단된다. 서양뒤영벌 수벌은 우화 6일에서 27일까지 교미가 가능하지만 평균 수벌의 교미나이는 12.1±1.3일이라고 보고( Tasei et al., 1998 )하여 본 실험의 결과와 다소의 차이를 보였다. 이는 단순히 교미율만을 가지고 조사한 결과와 교미율 뿐만 아니라 교미한 여왕벌을 가지고 사육한 결과까지 비교분석한 차이에 기인한다고 생각된다. 서양뒤영벌 수벌은 우화 6일 이후부터 정자가 정소관(또는 수정관 Vas deferentiae)으로 이동한다. 그 시기부터 정소관은 커지고 고환은 작아지며, 각 정소관의 중간부분은 결국 두꺼워지고, 성숙한 정자를 위한 저장기관으로서 제공되는 정소낭(Accessory testis)을 형성한다. 또한 정소관에서 정자수는 우화 13일 동안은 증가하지만 그 후부터는 감소한다( Dechateau and Marien, 1995).

Oviposition rate (A), rate of colony foundation (B) and rate of progeny-queen production (C) at the age of males. There was no significant difference in colony development at the age of males at p<0.05 using the Chi-square test.

Mating rate at the mating time of males. The mating time started at 10:00 and ended 17:00. The mating age of queen and male were 6 days and 10 days, respectively. There was significant difference in mating rate at the mating time of males at p<0.0001 using the Chi-square test.

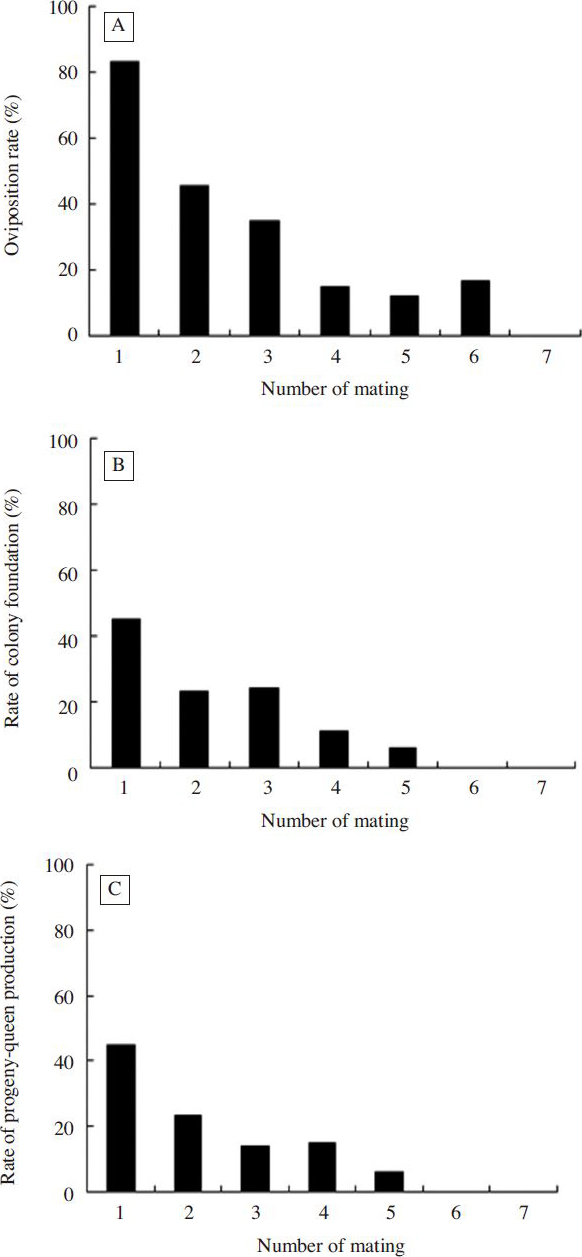

Oviposition rate (A), rate of colony foundation (B) and rate of progeny-queen production (C) at the number of mating of males. There was significant difference in colony development at the mating times of males at p<0.0001 using the Chi-square test.

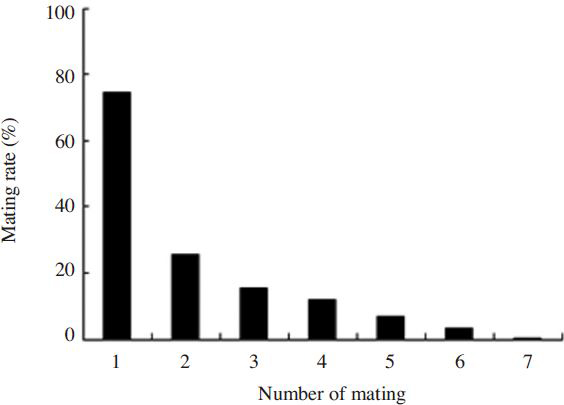

수벌의 교미횟수에 따른 교미율 조사

수벌의 교미능력을 알아보기 위해 우화 6일째 서양뒤영벌 여왕벌 300마리와 우화 10일째 수벌 300마리를 사용하여 수벌의 교미횟수에 따른 교미율을 조사하였다. Fig. 5에서 보는 바와 같이, 1회 교미율이 74.3%인데 반하여, 2회는 25.3%로 약 3배 정도 현저하게 낮아졌으나, 3회부터는 교미율이 완만하게 감소하는 경향을 보여주었다. 3회 교미율은 15.3%, 4회 11.7%, 5회 7.0%, 6회 3.3%, 7회 교미율은 0.3%이었다. 비록 낮은 비율이기는 하지만 서양뒤영벌 수벌은 7회까지 교미가 가능하였다( Fig. 7). 교미횟수에 따른 수벌의 교미율은 고도의 통계적 유의성이 있었다(Chi-square test: x 2=777.466, df=6, p=0.0001). Tasei et al.(1998) 은 수벌 69마리 중 50%가 1회 교미를 하였고, 8회까지 수벌이 교미하는 것을 확인하였다.

수벌의 교미횟수별 봉세발달 결과를 Fig. 6에 나타내었다. 산란율은( Fig. 6A), 1회 교미가 83.0%, 2회 교미(45.2%)는 1회 교미보다 약 1.8배, 3회(34.5%)은 약 2.4배 낮은 산란율을 보였다. 4회 교미부터는 산란율이 급격이 낮아져 14.8%, 5회 11.8%, 6회는 16.6%의 산란율을 보였다. 7회 교미한 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌은 산란하지 못하였다. 수벌의 교미횟수별 산란율은 통계적으로 고도의 유의성을 나타내었다(x 2=79.807, df=5, p=0.0001). 봉군형성률의 경우( Fig. 6B), 1회 교미가 45.0%, 2회 23.3%, 3회 24.1%, 4회 11.1%, 5회는 5.9%를 나타내었다. 수벌의 교미횟수별 봉군형성률은 고도의 유의차를 보였다(x 2=22.368, df=5, p=0.0001). Fig. 6C에서 보는 바와 같이, 신여왕출현봉군율은 봉군형성률과 비슷한 경향을 보여 1회 교미가 45.0%, 2회 23.3%, 3회 13.8%, 4회 14.8% 그리고 5회는 5.9%이었다. 수벌의 교미횟수별 신여왕출현봉군율 역시 고도의 통계적 유의성이 확인되었다(x 2=26.375, df=5, p=0.0001).

이상의 교미율과 산란율, 봉군형성률, 신여왕출현봉군율 등 봉세발달로 볼 때 1회 교미한 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌의 봉세발달이 2회 교미한 수벌과 교미한 여왕벌의 봉세발달이 거의 2배 이상의 차이를 보여, 우수종을 생산 보급하기 위해서는 수벌을 1회 교미하여 사용하는 것이 좋을 것으로 판단된다.

적 요

교미율 향상으로 서양뒤영벌( B. terrestris)의 우량형 질을 확보하기 위하여 여왕벌과 수벌의 성적 성숙시기 및 수벌의 교미능력을 조사하였다. 여왕벌의 성적 성숙시기 조사결과, 여왕벌은 우화직후에도 6.7%의 교미율을 나타내었고, 우화 10일이 85.0%로 가장 높았다. 우화 20일 이후에는 교미율이 급격하게 떨어지는 경향을 보였다. 산란율은 우화 6~8일이 81.3~81.8%로 가장 높았다. 봉군형성률과 신여왕출현봉군율은 우화 8일이 각각 43.8%, 37.5%로 가장 높게 나타났다. 반면에 수벌은 우화 직후에도 38.3%의 높은 교미율을 나타내었다. 우화 25일이 80.0%로 가장 높았으며, 우화 8일째는 76.6%의 교미율을 보였다. 산란율은 우화 6일이 76.9%로 가장 높았고, 우화 8일과 15일(75.0%), 우화 10일(72.7%) 순이었다. 봉군형성률과 신여왕출현봉율은 우화 10일이 각각 40.9%, 40.9%로 가장 높았다. 이상의 결과로 볼 때 여왕벌의 최적 교미성적 성숙시기는 우화 6~8일, 수벌은 우화 6~10일로 판단된다. 수벌의 교미능력 조사결과, 7회까지 교미가 가능한 것으로 나타났다. 수벌의 교미횟수별 교미율은 1회 74.3%, 2회 25.3%, 3회 15.3%, 4회는 11.7%, 5회, 7.0%, 6회 3.3%, 7회 0.3%이었다. 1회 교미한 여왕벌의 산란율, 봉군형성율 및 신여왕벌출현봉군율은 각각 83.0%, 45.0%, 45.0%로 2회 교미한 여왕벌의 봉세발달보다 약 2배나 좋은 것으로 나타났다. 따라서 우수형질을 생산 보급하기 위해서는 수벌을 1회만 교미하여 사용하는 것이 좋을 것으로 생각된다.

감사의 글

본 연구는 농촌진흥청 국립농업과학원 농업과학기술 연구개발사업(과제번호: PJ01005104)의 지원에 의해 이루어진 것입니다.

인용문헌

- Baer, B., E.D. Morgan, and P. Schmid-Hemple, (2001), A nonspecific fatty acid within the bumblebee mating plug prevent females form remating , PNAS, 98, p3926-3928.

- Baer, B., R. Maile, P. Schmid-Hemple, E.D. Morgan, and G.R. Jones, (2000), Chemistry of a mating plug in bumblebees, J. Chem. Ecol, 26, p1869-1875.

- Bergstom, G., (1981), Chemical composition, similarity and dissimilarity in volatile secretions: examples of indications of biological function , Les médiateurs chimiques agissant sur le comportment des insects, p289-296, Les colloques de I’NRA.

- Dag, A., and Y. Kammer, (2001), Comparison between the effectiveness of honeybee ( Apis mellifera) and bumblebee ( Bombus terrestris) as pollinators of greenhouse sweet pepper ( Capsicum annuum) , Am. Bee. J, 141, p447-448.

-

de Ruijter, A., (1997), Commercial bumblebee rearing and its implications, Proc, 7th Int. Symp. Pollination, Acat Hort, 437, p261-269.

[https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.1997.437.30]

- Djegham, Y., J.C. Verhaeghe, and P. Rasmout, (1994), Coupulation of Bombus terrestris L. (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in captivity , J. Apicul. Res, 33, p15-20.

- Duchateau, M.J., (1985), Analysis of some methods for rearing bumblebee colonies, Apidologie, 16, p225-227.

-

Duchateau, M.J., and H.H.W. Velthuis, (1988), Development and reproductive strategies in

Bombus terrestris

colonies

, Behavior, 107, p186-207.

[https://doi.org/10.1163/156853988X00340]

- Duchateau, M.J., and J. Mari`e`n, (1995), Sexual biology of haploid and diploid males in the bumblebee Bombus terrestris, Insectes Soc, 42, p255-266.

-

Duvoisin, N., B. Boris, and P. Schmid-Hemple, (1999), Sperm transfer and male competition in a bumblebee, Anim. Behav, 58, p743-749.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.1999.1196]

- Free, J.B., (1993), Insect pollination of crops, 2nd ed, Academic Press, London, p684.

-

Gallai, N., J.M. Salles, J. Settle, and B.E. Vaissiére, (2009), Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with

pollinator decline

, Ecol. Econ, 68, p810-821.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.06.014]

-

Greenleaf, S., and C. Kremen, (2006), Wild bee species increase tomato production but respond differently to surrounding

land use in Northern California

, Biol. Conserv, 133, p81-87.

[https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.05.025]

- Hannan, M.A., Y. Maeta, and K. Hoshikawa, (1998), Feeding behavior and food consumption in Bombus ( Bombus) ignitus under artificial condition (Hymenoptera: Apidae) , Entomol. Sci, 1, p27-32.

- Heinrich, B., (1979), Bumblebee economics, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Masss, p245.

- Honk, C.G., J van, H.H., W. Velthuis, and P.F. Röseler, (1978), A sex pheromone from the mandibular glands in bumblebee queens, Experientia, 34, p838-839.

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. (IPBES) , (2016), Summary for policy makers of the assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services on pollinators, pollination and food production , IPBES, (deliverable 3 (a)) of the 2014-2018 work programme.

- Masahiro, M., (2000), Pollination of crops with bumblebee colonies in Japan, Honeybee Sci, 21, p17-25.

- Michener, C.D., (2000), The bees of the world, Baltimore, JohnsHopkins University Press.

-

Morandin, L.A., and M.L. Winston, (2005), Wild bee abundance and seed production in conventional, organic, and genetically

modified canola

, Ecol. Appl, 15, p871-881.

[https://doi.org/10.1890/03-5271]

- Röseler, P. F., (1973), Die anzahl der spermien im receptaculum seminis von hummelköniginnen ( Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Bombinae) , Apidologie, 4, p267-274.

-

Sauter, A., and M.J.F. Brown, (2001), To copulate or not? The importance of female status and behavioural variation in

predicting copulation in bumblebee

, Anim. Behav, 62, p221-226.

[https://doi.org/10.1006/anbe.2001.1742]

- SPSS PASW® Statistics 18.0, (2007), PASW® Core System User’s Guide, SPSS inc, USA.

- Svensson, B.G., (1980), Species-isolating mechanisms in male bumble bees (Hymenoptera, Apidae), p176, Acta Universitatis upsaliensis.

- Tasei, J.N., C. Moinard, L. Moreau, B. Himpens, and S. Guyonnaud, (1998), Relationship between aging, mating and sperm production in captive Bombus terrestris, J. of Apicul. Res, 37, p107-113.

-

Velthuis, H.H.W., and A. van Doorn, (2006), A century of advances in bumblebee domestication and the economic and environmental

aspects of its commercialization for pollination

, Apidologie, 37, p421-451.

[https://doi.org/10.1051/apido:2006019]

- Williams, P.H., (1991), The bumble bees of the Kashmir Himalaya (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini) , Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. (Ent.), 60, p1-204.

- Williams, P.H., (1998), An annotated checklist of bumble bees with an analysis of patterns of description (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini) , Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. (Ent., 67, p79-152.

-

Winfree, R., T. Griswold, and C. Kremen, (2007), Effect of human disturbance on bee communities in a forested ecosystem

, Conserv. Biol, 21, p213-223.

[https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00574.x]

- Yoon, H.J., S.E. Kim, S.B. Lee, and I.G. Park, (2003), Effect of CO 2-treatment on oviposition and colony development of the bumblebee, Bombus ignitus, Korean J. Appl. Entomol, 42, p139-144.

- Yoon, H.J., S.E. Kim, Y.S. Kim, and S.B. Lee, (2004a), Colony developmental characteristics of the bumblebee queen, Bombus ignitus by the first oviposition day , Int. J. Indust. Entomol, 8, p139-143.

- Yoon, H.J., S.E. Kim, S.B. Lee, and H.S. Sim, (2004b), Comparison of the colony development in the bumblebee, Bombus ignitus. and B. terrestris, Kor. J. Appl. Entomol, 43, p117-121.

- Yoon, H.J., S.E. Kim, K.Y. Lee, S.B. Lee, and I.G. Park, (2008), Copultion environment favorable for colony development of the European bumblebee, Bombus terrestris, Int. J. Indust. Entomol, 16, p7-13.